편집 요약 없음 |

편집 요약 없음 |

||

| 235번째 줄: | 235번째 줄: | ||

This was an event of utmost importance in the history of the peninsula. It opened up to the world the southern portion of Korea, where there were stored up forces that were destined to dominate the whole peninsula and impress upon it a distinctive stamp. But before following Ki-jun southward we must turn back and watch the outcome of Wi-man’s treachery. | This was an event of utmost importance in the history of the peninsula. It opened up to the world the southern portion of Korea, where there were stored up forces that were destined to dominate the whole peninsula and impress upon it a distinctive stamp. But before following Ki-jun southward we must turn back and watch the outcome of Wi-man’s treachery. | ||

===Chapter III=== | |||

Wi-man.... establishes his kingdom.... extent.... power soon waned.... ambitious designs.... China aroused.... invasion of Korea.... U-gu tries to make peace.... siege of P‘yŭng-yang.... it falls.... the land redistributed.... the four provinces.... the two provinces. | |||

Having secured possession of Ki-jun’s kingdom, Wi-man set to work to establish himself firmly on the throne. He had had some experience in dealing with the wild tribes and now he exerted himself to the utmost in the task of securing the allegiance of as many of them as possible. He was literally surrounded by them, and this policy of friendliness was an 16absolute necessity. He succeeded so well that ere long he had won over almost all the adjacent tribes whose chieftains frequented his court and were there treated with such liberality that more than once they found themselves accompanying embassies to the court of China. | |||

It is said that when his kingdom was at its height it extended far into Liao-tung over all northern and eastern Korea and even across the Yellow Sea where it included Ch’ŭng-ju, China. Its southern boundary was the Han River. | |||

So long as Wi-man lived he held the kingdom together with a strong hand, for he was possessed of that peculiar kind of power which enabled him to retain the respect and esteem of the surrounding tribes. He knew when to check them and when to loosen the reins. But he did not bequeath this power to his descendants. His grandson, U-gŭ, inherited all his ambition without any of his tact. He did not realise that it was the strong hand and quick wit of his grandfather that had held the kingdom together and he soon began to plan a still further independence from China. He collected about him all the refugees and all the malcontents, most of whom had much to gain and little to lose in any event. He then cut off all friendly intercourse with the Han court and also prevented the surrounding tribes from sending their little embassies across the border. The Emperor could not brook this insult, and sent an envoy, Sŭp-ha, to expostulate with the headstrong U-gŭ; but as the latter would not listen, the envoy went back across the Yalu and tried what he could do by sending one of the older chiefs to ask what the king meant by his conduct. U-gŭ was still stubborn and when the chief returned to Sŭp-ha empty-handed he was put to death. Sŭp-ha paid the penalty for this rash act, for not many days after he had been installed governor of Liao-tung the tribe he had injured fell upon him and killed him. | |||

This was not done at the instigation of U-gŭ, but unfortunately it was all one to the Emperor. It was the “Eastern Barbarians” who, all alike, merited punishment. It was in 107 B.C. that the imperial edict went forth commanding all Chinese refugees in Korea to return at once, as U-gŭ was to be put down by the stern hand of war. | |||

17In the autumn of that year the two generals, Yang-bok and Sun-ch’i, invaded Korea at the head of a strong force; but U-gŭ was ready for them and in the first engagement scattered the invading army, the remnants of which took refuge among the mountains. It was ten days before they rallied enough to make even a good retreat. U-gŭ was frightened by his own good luck for he knew that this would still further anger the Emperor; so when an envoy came from China the king humbled himself, confessed his sins and sent his son to China as hostage together with a gift of 5,000 horses. Ten thousand troops accompanied him. As these troops were armed, the Chinese envoy feared there might be trouble after the Yalu had been crossed. He therefore asked the Prince to have them disarmed. The latter thought he detected treachery and so fled at night and did not stop until he reached his father’s palace in P‘yŭng-yang. The envoy paid for this piece of gaucherie with his head. | |||

Meanwhile Generals Yang-bok and Sun-ch’i had been scouring Liao-tung and had collected a larger army than before. With this they crossed the Ya-lu and marched on P‘yŭng-yang. They met with no resistance, for U-gŭ had collected all his forces at the capital, hoping perhaps that the severity of the weather would tire out any force that might be sent against him. The siege continued two months during which time the two generals quarreled incessantly. When the Emperor sent Gen. Kong Son-su to see what was the matter, Gen. Sun-ch’i accused his colleague of treason and had him sent back to China, where he lost his head. The siege, continued by Gen. Sun-ch’i, dragged on till the following summer and it would have continued longer had not a traitor within the town assassinated the king and fled to the Chinese camp. Still the people refused to make terms until another traitor opened the gates to the enemy. Gen. Sun-ch’i’s first act was to compel Prince Chang, the heir apparent, to do obeisance. But the people had their revenge upon the traitor who opened the gate for they fell upon him and tore him to pieces before he could make good his escape to the Chinese camp. | |||

Such was the miserable end of Wi-man’s treachery. He had cheated Ki-jun out of his kingdom which had lasted almost 18a thousand years, while the one founded by himself lasted only eighty-eight. It fell in the thirty-fourth year of the Han Emperor Wu-ti, in the year 106 B.C. | |||

Upon the downfall of Wi-man’s kingdom, the country was divided by the Chinese into four provinces called respectively Nang-nang, Im-dun, Hyŭn-do and Chin-bŭn. The first of these, Nang-nang, is supposed to have covered that portion of Korea now included in the three provinces of P‘yung-an, Whang-hă and Kyŭng-geui. Im-dun, so far as we can learn, was located about as the present province of Kang-wŭn, but it may have exceeded these limits. Hyŭn-do was about coterminous with the present province of Ham-gyŭng in the northeast. Chin-bŭn lay beyond the Yalu River but its limits can hardly be guessed at. It may have stretched to the Liao River or beyond. It is exceedingly doubtful whether the conquerors themselves had any definite idea of the shape or extent of these four provinces. Twenty-five years later, in the fifth year of Emperor Chao-ti 81 B.C. a change in administration was made. Chin-bŭn and Hyŭn-do were united to form a new province called P’yung-ju, while Im-dun and Nang-nang were thrown together to form Tong-bu. In this form the country remained until the founding of Ko-gu-ryŭ in the twelfth year of Emperor Yuan-ti, 36 B.C. | |||

It is here a fitting place to pause and ask what was the nature of these wild tribes that hung upon the flanks of civilization and, like the North American Indians, were friendly one day and on the war-path the next. Very little can be gleaned from purely Korean sources, but a Chinese work entitled the Mun-hön T’ong-go deals with them in some detail, and while there is much that is quite fantastic and absurd the main points tally so well with the little that Korean records say, that in their essential features they are probably as nearly correct as anything we are likely to find in regard to these aborigines (shall we say) of north-eastern Asia. | |||

===Chapter IV=== | |||

The wild tribes.... the “Nine Tribes” apocryphal.... Ye-mak.... position.... history.... customs.... Ye and Mak perhaps two.... Ok-jo 19.... position.... history.... customs.... North Ok-jo.... Eum-nu.... position.... customs.... the western tribes.... the Mal-gal group.... position.... customs.... other border tribes. | |||

As we have already seen, tradition gives us nine original wild tribes in the north named respectively the Kyŭn, Pang, Whang, Păk, Chŭk, Hyŭn, P’ung, Yang, and U. These we are told occupied the peninsula in the very earliest times. But little credence can be placed in this enumeration, for when it comes to the narration of events we find that these tribes are largely ignored and numerous other names are introduced. The tradition is that they lived in Yang-gok, “The Place of the Rising Sun.” In the days of Emperor T’ai-k’an of the Hsia dynasty, 2188 B.C. the wild tribes of the east revolted. In the days of Emperor Wu-wang, 1122 B.C. it is said that representatives from several of the wild tribes came to China bringing rude musical instruments and performing their queer dances. The Whe-i was another of the tribes, for we are told that the brothers of Emperor Wu-wang fled thither but were pursued and killed. Another tribe, the So-i, proclaimed their independence of China but were utterly destroyed by this same monarch. | |||

It is probable that all these tribes occupied the territory north of the Yalu River and the Ever-white Mountains. Certain it is that these names never occur in the pages of Korean history proper. Doubtless there was more or less intermixture and it is more than possible that their blood runs in the veins of Koreans today, but of this we cannot be certain. | |||

We must call attention to one more purely Chinese notice of early Korea because it contains perhaps the earliest mention of the word Cho-sŭn. It is said that in Cho-sŭn three rivers, the Chŭn-su, Yŭl-su, and San-su, unite to form the Yŭl-su, which flows by (or through) Nang-nang. This corresponds somewhat with the description of the Yalu River. | |||

We now come to the wild tribes actually resident in the peninsula and whose existence can hardly be questioned, whatever may be said about the details here given. | |||

We begin with the tribe called Ye-măk, about which there are full notices both in Chinese and Korean records. The Chinese accounts deal with it as a single tribe but the Korean accounts, which are more exact, tell us that Ye and 20Mak were two separate “kingdoms.” In all probability they were of the same stock but separate in government. | |||

Ye-guk (guk meaning kingdom) is called by some Ye-wi-guk. It is also know as Ch’ŭl. It was situated directly north of the kingdom of Sil-la, which was practically the present province of Kyŭng-sang, so its boundary must have been the same as that of the present Kang-wŭn Province. On the north was Ok-jŭ, on the east the Great Sea, and on the west Nang-nang. We may say then that Ye-guk comprised the greater portion of what is now Kang-wŭn Province. To this day the ruins of its capital may be seen to the east of the town of Kang-neung. In the palmy days of Ye-guk its capital was called Tong-i and later, when overcome by Sil-la, a royal seal was unearthed there and Hă-wang the king of Sil-la adopted it as his royal seal. After this town was incorporated into Sil-la it was known as Myŭng-ju. | |||

In the days of the Emperor Mu-je, 140 B.C., the king of Ye-guk was Nam-nyŭ. He revolted from Wi-man’s rule and, taking a great number of his people, estimated, fantastically of course, at 380,000, removed to Liao-tung, where the Emperor gave him a site for a settlement at Chang-hă-gun. Some accounts say that this colony lasted three years. Others say that after two years it revolted and was destroyed by the Emperor. There are indications that the remnant joined the kingdom of Pu-yŭ in the north-east for, according to one writer, the seal of Pu-yŭ contained the words “Seal of the King of Ye” and it was reported that the aged men of Pu-yŭ used to say that in the days of the Han dynasty they were fugitives. There was also in Pu-yŭ a fortress called the “Ye Fortress.” From this some argue that Nam-nyŭ was not a man of the east but of the north. Indeed it is difficult to see how he could have taken so many people so far especially across an enemy’s country. | |||

When the Chinese took the whole northern part of Korea, the Ye country was incorporated into the province of Im-dun and in the time of the Emperor Kwang-mu the governor of the province resided at Kang-neung. The Emperor received an annual tribute of grass-cloth, fruit and horses. | |||

The people of Ye-guk were simple and credulous, and not naturally inclined to warlike pursuits. They were modest 21and unassuming, nor were they fond of jewels or finery. Their peaceful disposition made them an easy prey to their neighbors who frequently harassed them. In later times both Ko-gu-ryŭ and Sil-la used Ye-guk soldiers in part in effecting their conquests. People of the same family name did not intermarry. If a person died of disease his house was deserted and the family found a new place of abode. We infer from this that their houses were of a very poor quality and easily built; probably little more than a rude thatch covering a slight excavation in a hill-side. The use of hemp was known as was also that of silk, though this was probably at a much later date. Cotton was also grown and woven. By observing the stars they believed they could foretell a famine; from which we infer that they were mainly an agricultural people. In the tenth moon they worshipped the heavens, during which ceremony they drank, sang and danced. They also worshipped the “Tiger Spirit.” Robbery was punished by fining the offender a horse or a cow. In fighting they used spears as long as three men and not infrequently several men wielded the same spear together. They fought entirely on foot. The celebrated Nang-nang bows were in reality of Ye-guk make and were cut out of pak-tal wood. The country was infested with leopards. The horses were so small that mounted men could ride under the branches of the fruit trees without difficulty. They sold colored fish skins to the Chinese, the fish being taken from the eastern sea. | |||

We are confronted by the singular statement that at the time of the Wei dynasty in China, 220-294 A.D. Ye-guk swore allegiance to China and despatched an envoy four times a year. There was no Ye-mak in Korea at that time and this must refer to some other Ye tribe in the north. It is said they purchased exemption from military duty by paying a stipulated annual sum. This is manifestly said of some tribe more contiguous to China than the one we are here discussing. | |||

Măk-guk, the other half of Ye-măk, had its seat of government near the site of the present town of Ch’un-ch’ŭn. Later, in the time of the Sil-la supremacy, it was known as U-su-ju. It was called Ch’ŭn-ju in the time of the Ko-ryŭ rule. | |||

The ancient Chinese work, Su-jun, says that in the days 22of Emperor Mu-song (antedating Ki-ja) the people of Wha-ha Man-măk came and did obeisance to China. This may have been the Korean Măk. Mencius also makes mention of a greater Măk and a lesser Măk. In the time of the Han dynasty they spoke of Cho-sün, Chin-bŭn and Ye-măk. Mencius’ notice of a greater and lesser Măk is looked upon by some as an insult to the memory of Ki-ja, as if he had called Ki-ja’s kingdom a wild country; but the above mention of the three separately is quoted to show that Mencius had no such thought. | |||

The annals of Emperor Mu-je state, in a commentary, that Măk was north of Chin-han and south of Ko-gu-ryŭ and Ok-jŭ and had the sea to the east, a description which exactly suits Ye-măk as we know it. | |||

The wild tribe called Ok-jŭ occupied the territory east of Kă-ma San and lay along the eastern sea-coast. It was narrow and long, stretching a thousand li along the coast in the form of a hook. This well describes the contour of the coast from a point somewhat south of the present Wŭn-san northward along the shore of Ham-gyŭng Province. On its south was Ye-măk and on its north were the wild Eum-nu and Pu-yŭ tribes. It consisted of five thousand houses grouped in separate communities that were quite distinct from each other politically, and a sort of patriarchal government prevailed. The language was much like that of the people of Ko-gu-ryŭ. | |||

When Wi-man took Ki-jun’s kingdom, the Ok-jŭ people became subject to him, but later, when the Chinese made the four provinces, Ok-jŭ was incorporated into Hyŭn-do. As Ok-jŭ was the most remote of all the wild tribes from the Chinese capital, a special governor was appointed over her, called a Tong-bu To-wi, and his seat of government was at Pul-lă fortress. The district was divided into seven parts, all of which were east of Tan-dan Pass, perhaps the Tă-gwul Pass of to-day. In the sixth year of the Emperor Kwang-mu, 31 A.D., it is said that the governorship was discontinued and native magnates were put at the head of affairs in each of the seven districts under the title Hu or Marquis. Three of the seven districts were Wha-ye, Ok-jŭ and Pul-lă. It is said that the people of Ye-guk were called in to build the government houses in these seven centers. | |||

23When Ko-gu-ryŭ took over all northern Korea, she placed a single governor over all this territory with the title Tă-in. Tribute was rendered in the form of grass-cloth, fish, salt and other sea products. Handsome women were also requisitioned. The land was fertile. It had a range of mountains at its back and the sea in front. Cereals grew abundantly. The people are described as being very vindictive. Spears were the weapons mostly used in fighting. Horses and cattle were scarce. The style of dress was the same as that of Ko-gu-ryŭ. | |||

When a girl reached the age of ten she was taken to the home of her future husband and brought up there. Having attained a marriageable age she returned home and her fiancé then obtained her by paying the stipulated price. | |||

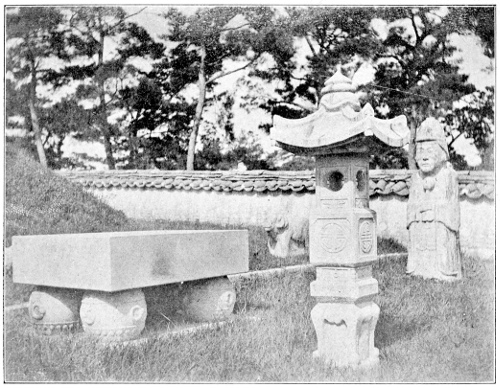

Dead bodies were buried in a shallow grave and when only the bones remained they were exhumed and thrust into a huge hollowed tree trunk which formed the family “vault.” Many generations were thus buried in a single tree trunk. The opening was at the end of the trunk. A wooden image of the dead was carved and set beside this coffin and with it a bowl of grain. | |||

The northern part of Ok-jŭ was called Puk Ok-jŭ or “North Ok-jŭ.” The customs of these people were the same as those of the south except for some differences caused by the proximity of the Eum-nu tribe to the north, who were the Apaches of Korea. Every year these fierce people made a descent upon the villages of the peaceful Ok-jŭ, sweeping everything before them. So regular were these incursions that the Ok-jŭ people used to migrate to the mountains every summer, where they lived in caves as best they could, returning to their homes in the late autumn. The cold of winter held their enemies in check. | |||

We are told that a Chinese envoy once penetrated these remote regions. He asked “Are there any people living beyond this sea?” (meaning the Japan Sea.) They replied “Sometimes when we go out to fish and a tempest strikes us we are driven ten days toward the east until we reach islands where men live whose language is strange and whose custom it is each summer to drown a young girl in the sea.” Another said “Once some clothes floated here which were like ours except that the sleeves were as long as the height of a man.” 24Another said “A boat once drifted here containing a man with a double face, one above the other. We could not understand his speech and as he refused to eat he soon expired.” | |||

The tribe of Ok-jŭ was finally absorbed in Ko-gu-ryŭ in the fourth year of King T’ă-jo Wang. | |||

The Eum-nu tribe did not belong to Korea proper but as its territory was adjacent to Korea a word may not be out of place. It was originally called Suk-sin. It was north of Ok-jŭ and stretched from the Tu-man river away north to the vicinity of the Amur. Its most famous mountain was Pul-ham San, It is said to have been a thousand li to the north-east of Pu-yŭ. The country was mountainous and there were no cart roads. The various cereals were grown, as well as hemp. | |||

The native account of the people of Eum-nu is quite droll and can hardly be accepted as credible. It tells us that the people lived in the trees in summer and in holes in the ground in winter. The higher a man’s rank the deeper he was allowed to dig. The deepest holes were “nine rafters deep.” Pigs were much in evidence. The flesh was eaten and the skins were worn. In winter the people smeared themselves an inch thick with grease. In summer they wore only a breach-cloth. They were extremely filthy. In the center of each of these winter excavations was a common cesspool about which everything else was clustered. The extraordinary statement is made that these people picked up pieces of meat with their toes and ate them. They sat on frozen meat to thaw it out. There was no king, but a sort of hereditary chieftainship prevailed. If a man desired to marry he placed a feather in the hair of the damsel of his choice and if she accepted him she simply followed him home. Women did not marry twice, but before marriage the extreme of latitude was allowed. Young men were more respected than old men. They buried their dead, placing a number of slaughtered pigs beside the dead that he might have something to eat in the land beyond the grave. The people were fierce and cruel, and even though a parent died they did not weep. Death was the penalty for small as well as great offences. They had no form of writing and treaties were made only by word of mouth. In the days of Emperor Yüan-ti of the Eastern Tsin dynasty, an envoy from this tribe was seen in the Capital of China. | |||

25We have described the tribes of eastern Korea. A word now about the western part of the peninsula. All that portion of Korea lying between the Han and Yalu rivers constituted what was known as Nang-nang and included the present provinces of P‘yŭng-an and Whang-hă together with a portion of Kyŭng-geui. It was originally the name of a single tribe whose position will probably never be exactly known; but it was of such importance that when China divided northern Korea into four provinces she gave this name of Nang-nang to all that portion lying, as we have said, between the Han and the Yalu. The only accounts of these people are given under the head of the Kingdom of Ko-gu-ryŭ which we shall consider later. But between Nang-nang and the extreme eastern tribes of Ok-jŭ there was a large tract of country including the eastern part of the present province of P’yŭng-an and the western part of Ham-gyŭng. This was called Hyŭn-do, and the Chinese gave this name to the whole north-eastern part of Korea. No separate accounts of Hyŭn-do seem to be now available. | |||

Before passing to the account of the founding of the three great kingdoms of Sil-la, Păk-je and Ko-gu-ryŭ, we must give a passing glance at one or two of the great border tribes of the north-west. They were not Koreans but exercised such influence upon the life of Korea that they deserve passing notice. | |||

In that vast tract of territory now known as Manchuria there existed, at the time of Christ, a group of wild tribes known under the common name Mal-gal. The group was composed of seven separate tribes, named respectively—Songmal, Păk-tol, An-gŭ-gol, Pul-lal, Ho-sil, Heuk-su (known also as the Mul-gil) and the Păk-san. Between these tribes there was probably some strong affinity, although this is argued only from the generic name Mal-gal which was usually appended to their separate names, and the fact that Mal-gal is commonly spoken of as one. The location of this group of tribes is determined by the statement (1) that it was north of Ko-gu-ryŭ and (2) that to the east of it was a tribe anciently called the Suk-sin (the same as the Eum-nu,) and (3) that it was five thousand li from Nak-yang the capital of China. We are also told that in it was the great river Sog-mal which was three li wide referring it would seem to the Amur River. These tribes, though 26members of one family, were constantly fighting each other and their neighbors and the ancient records say that of all the wild tribes of the east the Mal-gal were the most feared by their neighbors. But of all the Mal-gal tribes the Heuk-su were the fiercest and most warlike. They lived by hunting and fishing. The title of their chiefs was Tă-mak-pul-man-lol-guk. The people honored their chiefs and stood in great fear of them. It is said that they would not attend to the duties of nature on a mountain, considering, it would seem, that there is something sacred about a mountain. They lived in excavations in the sides of earth banks, covering them with a rough thatch. The entrance was from above. Horses were used but there were no other domestic animals except pigs. Their rude carts were pushed by men and their plows were dragged by the same. They raised a little millet and barley, and cultivated nine kinds of vegetables. The water there, was brackish owing to the presence of a certain kind of tree the bark of whose roots tinged the water like an infusion. They made wine by chewing grain and then allowing it to ferment. This was very intoxicating. For the marriage ceremony the bride wore a hempen skirt and the groom a pig skin with a tiger skin over his head. Both bride and groom washed the face and hands in urine. They were the filthiest of all the wild tribes. They were expert archers, their bows being made of horn, and the arrows were twenty-three inches long. In summer a poison was prepared in which the arrow heads were dipped. A wound from one of these was almost instantly fatal. The almost incredible statement is made in the native accounts that the dead bodies of this people were not interred but were used in baiting traps for wild animals. | |||

Besides the Mal-gal tribes there were two others of considerable note, namely the Pal-hă and the Kŭ-ran of which special mention is not here necessary, though their names will appear occasionally in the following pages. They lived somewhere along the northern borders of Korea, within striking distance. The last border tribe that we shall mention is the Yŭ-jin whose history is closely interwoven with that of Ko-gu-ryŭ. They were the direct descendants, or at least close relatives, of the Eum-nu people. They were said to have been the very lowest and weakest of all the wild tribes, in fact 27a mongrel tribe, made up of the offscourings of all the others. They are briefly described by the statement that if they took up a handful of water it instantly turned black. They were good archers and were skilful at mimicing the deer for the purpose of decoying it. They ate deer flesh raw. A favorite form of amusement was to make tame deer intoxicated with wine and watch their antics. Pigs, cattle and donkeys abounded. They used cattle for burden and the hides served for covering. The houses were roofed with bark. Fine horses were raised by them. It was in this tribe that the great conquerer of China, A-gol-t’a, arose, who paved the way for the founding of the great Kin dynasty a thousand years or more after the beginning of our era. | |||

===Chapter VI=== | |||

The founding of Sil-la, Ko-gu-ryu, and Pak-je.... Sil-la.... legend.... growth.... Tsushima a vassal.... credibility of accounts.... Japanese relations.... early vicissitudes.... Ko-gu-ryu.... four Pu-yus.... legend.... location of Pu-yu.... Chu-mong founds Ko-gu-ryu.... growth and extent.... products.... customs.... religious rites.... official grades.... punishments.... growth eastward.... Pak-je.... relations between Sil-la and Pak-je.... tradition of founding of Pak-je.... opposition of wide tribes.... the capital moved.... situation of the peninsula at the time of Christ. | |||

In the year 57 B.C. the chiefs of the six great Chin-han states, Yŭn-jun-yang-san, Tol-san-go-hö, Cha-sa-jin-ji, Mu-san-dă-su, Keum san-ga-ri and Myŭng-whal-san-go-ya held a great council at Yun-chŭn-yang and agreed to merge their separate fiefs into a kingdom. They named the capital of the new kingdom Sŭ-ya-bŭl, from which the present word Seoul is probably derived, and it was situated where Kyöng-ju now stands in Kyüng-sang Province. At first the name applied both to the capital and to the kingdom. | |||

They placed upon the throne a boy of thirteen years, named Hyŭk-kŭ-se, with the royal title Kŭ-sŭ-gan. It is said that his family name was Pak, but this was probably an afterthought derived from a Chinese source. At any rate he is generally known as Pak Hyŭk-kŭ-se. The story of his advent is typically Korean. A company of revellers beheld upon a mountain side a ball of light on which a horse was seated. They approached it and as they did so the horse rose straight in air and disappeared, leaving a great, luminous egg. This soon opened of itself and disclosed a handsome boy. This wonder was accompanied by vivid light and the noise of thunder. Not long after this another wonder was seen. Beside the Yŭn-yüng Spring a hen raised her wing and from her side came forth a female child with a mouth like a bird’s bill, but when they washed her in the spring the bill fell off and left her like other children. For this reason the well was named the Pal-ch’ŭn which refers to the falling of the bill. Another tradition says that she was formed from the rib of a dragon which inhabited the spring. In the fifth year of his reign the youthful king espoused this girl and they typify to all Koreans the perfect marriage. | |||

As this kingdom included only six of the Chin-han states, it would be difficult to give its exact boundaries. From the very first it began to absorb the surrounding states, until at last it was bounded on the east and south by the sea alone, while it extended north to the vicinity of the Han River and westward to the borders of Na-han, or to Chi-ri San. It took her over four hundred years to complete these conquests, many of which were bloodless while others were effected at the point of the sword. It was not until the twenty-second generation that the name Sil-la was adopted as the name of this kingdom. | |||

35It is important to notice that the island of Tsushima, whether actually conquered by Sil-la or not, became a dependency of that Kingdom and on account of the sterility of the soil the people of that island were annually aided by the government. It was not until the year 500 A.D. or thereabouts that the Japanese took charge of the island and placed their magistrate there. From that time on, the island was not a dependency of any Korean state but the relations between them were very intimate, and there was a constant interchange of goods, in a half commercial and half political manner. There is nothing to show that the daimyos of Tsushima ever had any control over any portion of the adjacent coast of Korea. | |||

It gives one a strong sense of the trustworthiness of the Korean records of these early days to note with what care the date of every eclipse was recorded. At the beginning of each reign the list of the dates of solar eclipses is given. For instance, in the reign of Hyŭk-kŭ-se they occurred, so the records say, in the fourth, twenty-fourth, thirtieth, thirty-second, forty-third, forty-fifth, fifty-sixth and fifty-ninth years of his reign. According to the Gregorian calendar this would mean the years 53, 31, 27, 25, 14, 12 B.C. and 2. A.D. If these annals were later productions, intended to deceive posterity, they would scarcely contain lists of solar eclipses. The marvelous or incredible stories given in these records are given only as such and often the reader is warned not to put faith in them. | |||

The year 48 B.C. gives us the first definite statement of a historical fact regarding Japanese relations with Korea. In that year the Japanese pirates stopped their incursions into Korea for the time being. From this it would seem that even at that early date the Japanese had become the vikings of the East and were carrying fire and sword wherever there was enough water to float their boats. It would also indicate that the extreme south of Korea was not settled by Japanese, for it was here that the Japanese incursions took place. | |||

In 37 B.C. the power of the little kingdom of Sil-la began to be felt in surrounding districts and the towns of Pyön-han joined her standards. It was probably a bloodless conquest, the people of Pyön-han coming voluntarily into Sil-la. In 37 B.C. the capital of Sil-la, which had received the secondary 36name Keum-sŭng, was surrounded by a wall thirty-five li, twelve miles, long. The city was 5,075 paces long and 3,018 paces wide. The progress made by Sil-la and the evident tendency toward centralisation of all power in a monarchy aroused the suspicion of the king of Ma-han who, we must remember, had considered Chin-han as in some sense a vassal of Ma-han. For this reason the king of Sil-la, in 19 B.C., sent an envoy to the court of Ma-han with rich presents in order to allay the fears of that monarch. The constant and heavy influx into Sil-la of the fugitive Chinese element also disturbed the mind of that same king, for he foresaw that if this went unchecked it might mean the supremacy of Sil-la instead of that of Ma-han. This envoy from Sil-la was Ho-gong, said to have been a native of Japan. He found the king of Ma-han in an unenviable frame of mind and it required all his tact to pacify him, and even then he succeeded so ill that had not the Ma-han officials interfered the king would have had his life. The following year the king of Ma-han died and a Sil-la embassy went to attend the obsequies. They were anxious to find opportunity to seize the helm of state in Ma-han and bring her into the port of Sil-la, but this they were strictly forbidden to do by their royal master who generously forebore to take revenge for the insult of the preceding year. | |||

As this was the year, 37 B.C., which marks the founding of the powerful kingdom of Ko-gur-yŭ, we must turn our eyes northward and examine that important event. | |||

As the founder of Ko-gur-yŭ originated in the kingdom of Pu-yŭ, it will be necessary for us to examine briefly the position and status of that tribe, whose name stands prominently forth in Korean history and tradition. There were four Pu-yŭs in all; North Pu-yŭ, East Pu-yŭ, Chŭl-bŭn Pu-yŭ and South Pu-yŭ. We have already, under the head of the Tan-gun, seen that tradition gives to Pu-ru his son, the honor of having having been the founder of North Pu-yŭ, or Puk Pu-yŭ as it is commonly called. This is quite apocryphal but gives us at least a precarious starting point. This Puk Pu-yŭ is said by some to have been far to the north in the vicinity of the Amur River or on one of its tributaries, a belief which is sustained to a certain extent by some inferences to be deduced from the following legend. | |||

37It must have been about fifty years before the beginning of our era that King Hă-bu-ru sat upon the throne of North Pu-yŭ. His great sorrow was that Providence had not given him a son. Riding one day in the forest he reached the bank of a swift rushing stream and there dismounting he besought the Great Spirit to grant him a son. Turning to remount he found the horse standing with bowed head before a great boulder while tears were rolling down its face. He turned the boulder over and found beneath it a child of the color of gold but with a form resembling a toad. Thus was his prayer answered. He took the curious child home and gave it the name Keum-wa or “Golden Toad.” Soon after this the kingdom removed to East Pu-yŭ, or Tong Pu-yŭ, somewhere near the “White Head Mountain,” known as Păk-tu San. | |||

Arriving at the age of manhood, Keum-wa looked about for a wife. As he was walking along the shore of U-bal-su (whether river or sea we do not know) he found a maiden crying. Her name was Yu-wha, “Willow Catkin.” To his inquiries she replied that she was daughter of the Sea King, Ha-băk, but that she had been driven from home because she had been enticed away and ravished by a spirit called Ha-mo-su. Keum-wa took her home as his wife but shut her in a room to which the sun-light had access only by a single minute aperture. Marvelous to relate a ray of light entered and followed her to whatever part of the room she went. By it she conceived and in due time gave birth to an egg, as large as five “measures.” Keum-wa in anger threw it to the pigs and dogs but they would not touch it. Cattle and horses breathed upon it to give it warmth. A stork from heaven settled down upon it and warmed it beneath her feathers. Keum-wa relented and allowed Yu-wha to bring it to the palace, where she wrapped it in silk and cotton. At last it burst and disclosed a fine boy. This precocious youth at seven years of age was so expert with the bow that he won the name of Chu-mong, “Skillful Archer.” He was not a favorite with the people and they tried to compass his death but the king protected him and made him keeper of the royal stables. Like Jacob of Holy Writ he brought his wits to bear upon the situation. By fattening the poorer horses and making the good ones lean he succeeded in reserving for his own use the 38fleetest steeds. Thus in the hunt he always led the rout and secured the lion’s share of the game. For this his seven brothers hated him and determined upon his death. By night his mother sought his bed-side and whispered the word of warning. Chu-mong arose and with three trusty councillors, O-i, Ma-ri and Hyŭp-pu, fled southward until he found his path blocked by the Eum-ho River. There was neither boat, bridge nor ford. Striking the surface of the water with his bow he called upon the spirit of the river to aid him, for behind him the plain smoked with the pursuing hoof-beats of his brothers’ horses. Instantly there came up from the depths of the river a shoal of fish and tortoises who lay their backs together and thus bridged the stream. | |||

Fantastic as this story seems, it may have an important bearing upon the question of the location of Pu-yŭ. Can we not see in this great shoal of fish a reference to the salmon which, at certain seasons, run up the Amur and its tributaries in such numbers that the water is literally crowded with them? If there is any weight to this argument the kingdom of Pu-yŭ, from which Chu-mong came, must have been, as some believe, along the Sungari or some other tributary of the Amur. | |||

Leaving his brothers baffled on the northern bank, Chu-mong fared southward till he reached Mo-tun-gok by the Po-sul River where he met three men, Chă-sa, clothed in grass cloth, Mu-gol in priestly garb and Muk-hŭ, in seaweed. They joined his retinue and proceeded with him to Chŭl-bon, the present town of Song-ch’ŭn, where he founded a kingdom. He gave it the name of Ko-gu-ryŭ, from Ko, his family name, and Ku-ryŭ, a mountain in his native Pu-yŭ. Some say the Ko is from the Chinese Kao, “high,” referring to his origin. This kingdom is also known by the name Chŭl-bon Pu-yu. It is said that Pu-ryu River flowed by the capital. These events occurred, if at all, in the year 37 B.C. This was all Chinese land, for it was a part of the great province of Tong-bu which had been erected by the Emperor So-je (Chao-ti) in 81 B.C. Only one authority mentions Chu-mong’s relations with Tong-bu. This says that when he erected his capital at Chŭl-bon he seized Tong-bu. China had probably held these provinces with a very light hand and the founding of a 39vigorous native monarchy would be likely to attract the semi-barbarous people of northern Korea. Besides, the young Ko-gu-ryŭ did not seize the whole territory at once but gradually absorbed it. It is not unlikely that China looked with complacency upon a native ruler who, while recognising her suzerainty, could at the same time hold in check the fierce denizens of the peninsula. | |||

We are told that the soil of Ko-gu-ryŭ was fertile and that the cereals grew abundantly. The land was famous for its fine horses and its red jade, its blue squirrel skins and its pearls. Chu-mong inclosed his capital in a heavy stockade and built store-houses and a prison. At its best the country stretched a thousand li beyond the Yalu River and southward to the banks of the Han. It comprised the Nang-nang tribe from which Emperor Mu-je named the whole north-western portion of Korea when he divided northern Korea into four provinces. On the east was Ok-ju and on its north was Pu-yŭ. It contained two races of people, one living among the mountains and the other in the plains. It is said they had a five-fold origin. There were the So-ro-bu, Chŭl-lo-bu, Sun-no-bu, Kwan-no-bu and Kye-ro-bu. The kings at first came from the So-ro-bu line but afterwards from the Kye-ro-bu. This probably refers to certain family clans or parties which existed at the time of Chu-mong’s arrival and which were not discontinued. Chu-mong is said to have married the daughter of the king of Chŭl-bon and so he came into the control of affairs in a peaceful way and the institutions of society were not particularly disturbed. | |||

Agriculture was not extensively followed. In the matter of food they were very frugal. Their manners and customs were somewhat like those of Pu-yŭ but were not derived from that kingdom. Though licentious they were fond of clean clothes. At night both sexes gathered in a single apartment and immorality abounded. Adultery, however, if discovered, was severely punished. In bowing it was customary for these people to throw out one leg behind. While travelling, men more often ran than walked. The worship of spirits was universal. In the autumn there was a great religious festival. In the eastern part of the peninsula there was a famous cave called Su-sin where a great religious gathering occurred each 40autumn. Their religious rites included singing and drinking. At the same time captives were set free. They worshipped likewise on the eve of battle, slaughtering a bullock and examining the body for omens. | |||

Swords, arrows and spears were their common weapons. A widow usually became the wife of her dead husband’s brother. When a great man died it was common to bury one or more men alive with his body. The statement that sometimes as many as a hundred were killed is probably an exaggeration. These characteristics were those of the Nang-nang people as well as of the rest of Ko-gu-ryŭ. The highest official grades were called Sang-ga-dă, No-p’ă, Ko-ju-dă. Some say their official grades were called by the names of animals, as the “horse grade” the “dog grade” the “cow grade.” There were special court garments of silk embroidered with gold and silver. The court hat was something like the present kwan or skull-cap. There were few prisoners. If a man committed a crime he was summarily tried and executed, and his wife and children became slaves. Thieves restored twelve-fold. Marriage always took place at the bride’s house. The dead were wrapped in silks and interred, and commonly the entire fortune of the deceased was exhausted in the funeral ceremony. The bodies of criminals were left unburied. The people were fierce and violent and thieving was common. They rapidly corrupted the simpler and cleaner people of the Ye-măk and Ok-jŭ tribes. | |||

No sooner had Chu-mong become firmly established in his new capital than he began to extend the limits of his kingdom. In 35 B.C. he began a series of conquests which resulted in the establishment of a kingdom destined to defy the power of China for three quarters of a millennium. His first operations were against the wild people to the east of him. The first year he took Pu-ryu on the Ya-lu, then in 29 B.C. he took Hăng-in, a district near the present Myo-hyang San. In 27 B.C. he took Ok-jŭ, thus extending his kingdom to the shore of eastern Korea. In 23 B.C. he learned that his mother had died in far off Pu-yŭ and he sent an embassy thither to do honor to her. | |||

The year 18 B.C. beheld the founding of the third of the great kingdoms which held the triple sceptre of Korea, and 41we must therefore turn southward and examine the events which led up to the founding of the kingdom of Păk-je. | |||

When Chu-mong fled southward from Pu-yŭ he left behind him a wife and son. The latter was named Yu-ri. Tradition says that one day while playing with pebbles in the street he accidentally broke a woman’s water jar. In anger she exclaimed “You are a child without a father.” The boy went sadly home and asked his mother if it was true. She answered yes, in order to see what the boy would do. He went out and found a knife and was on the point of plunging it into his body when she threw herself upon him saying “Your father is living and is a great king in the south. Before he left he hid a token under a tree, which you are to find and take to him.” The boy searched every where but could not find the tree. At last, wearied out, he sat down behind the house in despair, when suddenly he heard a sound as of picking, and noticing that it came from one of the posts of the house he said “This is the tree and I shall now find the token.” Digging beneath the post he unearthed the broken blade of a sword. With this he started south and when he reached his father’s palace he showed the token. His father produced the other half of the broken blade and as the two matched he received the boy and proclaimed him heir to the throne. | |||

But he had two other sons by a wife whom he had taken more recently. They were Pi-ryu and On-jo. When Yu-ri appeared on the scene these two brothers, knowing how proverbially unsafe the head of a king’s relative is, feared for their lives and so fled southward. Ascending Sam-gak San, the mountain immediately behind the present Seoul, they surveyed the country southward. Pi-ryu the elder chose the country to the westward along the sea. On-jo chose to go directly south. So they separated, Pi-ryu going to Mi-ch’u-hol, now In-ch’ŭn near Chemulpo, where he made a settlement. On-jo struck southward into what is now Ch’ung-ch’ŭng Province and settled at a place called Eui-rye-sŭng, now the district of Chik-san. There he was given a generous tract of land by the king of Ma-han; and he forthwith set up a little kingdom which he named South Pu-yŭ. The origin of the name Păk-je is not definitely known. Some say it was because a hundred men constituted the whole of On-jo’s party. Others say 42that it was at first called Sip-je and then changed to Păk-je when their numbers were swelled by the arrival of Pi-ryu and his party. The latter had found the land sterile and the climate unhealthy at Mi-ch’u-hol and so was constrained to join his brother again. On the other hand we find the name Păk-je in the list of original districts of Ma-han and it is probable that this new kingdom sprang up in the district called Păk-je and this name became so connected with it that it has came down in history as Păk-je, while in truth it was not called so by its own people. It the same way Cho-sŭn is known today by the medieval name Korea. Not long after Pi-ryu rejoined his brother he died of chagrin at his own failure. | |||

It must not be imagined that these three kingdoms of Sil-la, Ko-gu-ryŭ and Păk-je, which represented so strongly the centripetal idea in government, were allowed to proceed without vigorous protests from the less civilized tribes about them. The Mal-gal tribes in the north, the Suk-sin and North Ok-jŭ tribe in the north-east and Ye-măk in the east made fierce attacks upon them as opportunity presented. The Mal-gal tribes in particular seem to have penetrated southward even to the borders of Păk-je, probably after skirting the eastern borders of Ko-gu-ryŭ. Nominally Ko-gu-ryŭ held sway even to the Japan Sea but practically the wild tribes roamed as yet at will all through the eastern part of the peninsula. In the eighth year of On-jo’s reign, 10 B.C., the Mal-gal forces besieged his capital and it was only after a most desperate fight that they were driven back. On-jo found it necessary to build the fortresses of Ma-su-sŭng and Ch’il-chung-sŭng to guard against such inroads. At the same time the Sŭn-bi were threatening Ko-gu-ryŭ on the north, but Gen. Pu Bun-no lured them into an ambush and routed them completely. The king rewarded him with land, horses and thirty pounds of gold, but the last he refused. | |||

The next year the wild men pulled down the fortresses lately erected by King On-jo and the latter decided that he must find a better site for his capital. So he moved it to the present site of Nam-han, about twenty miles from the present Seoul. At the same time he sent and informed the king of Ma-han that he had found it necessary to move. The following year he enclosed the town in a wall and set to work teaching 43agriculture to the people throughout the valley of the Han River which flowed near by. | |||

In the year which saw the birth of Christ the situation of affairs in Korea was as follows. In the north, Ko-gu-ryŭ, a vigorous, warlike kingdom, was making herself thoroughly feared by her neighbors; in the central western portion was the little kingdom of Păk-je, as yet without any claims to independence but waiting patiently for the power of Ma-han so to decline as to make it possible to play the serpent in the bosom as Wi-man had done to Ki-ja’s kingdom. In the south was Sil-la, known as a peaceful power, not needing the sword because her rule was so mild and just that people from far and near flocked to her borders and craved to become her citizens. It is one of the compensations of history that Sil-la, the least martial of them all, in an age when force seemed the only arbiter, should have finally overcome them all and imposed upon them her laws and her language. | |||

2023년 2월 18일 (토) 14:16 판

이 책은 Project Gutenberg의 일환으로 제작된 ebook으로 저작권이 없습니다.

HOMER B. HULBERT, A.M., F.R.G.S.

Seoul, 1905

The Methodist Publishing House

Preface

The sources from which the following History of Korea is drawn are almost purely Korean. For ancient and medieval history the Tong-sa Kang-yo has been mainly followed. This is an abstract in nine volumes of the four great ancient histories of the country. The facts here found were verified by reference to the Tong-guk Tong-gam, the most complete of all existing ancient histories of the country. Many other works on history, geography and biography have been consulted, but in the main the narrative in the works mentioned above has been followed.

A number of Chinese works have been consulted, especially the Mun-hon Tong-go wherein we find the best description of the wild tribes that occupied the peninsula about the time of Christ.

It has been far more difficult to obtain material for compiling the history of the past five centuries. By unwritten law the history of no dynasty in Korea has ever been published until after its fall. Official records are carefully kept in the government archives and when the dynasty closes these are published by the new dynasty. There is an official record which is published under the name of the Kuk-cho Po-gam but it can in no sense be called a history, for it can contain nothing that is not complimentary to the ruling house and, moreover, it has not been brought down even to the opening of the 19th century. It has been necessary therefore to find private iimanuscript histories of the dynasty and by uniting and comparing them secure as accurate a delineation as possible of the salient features of modern Korean history. In this I have enjoyed the services of a Korean scholar who has made the history of this dynasty a special study for the past twenty-five years and who has had access to a large number of private manuscripts. I withhold his name by special request. By special courtesy I have also been granted access to one of the largest and most complete private libraries in the capital. Japanese records have also been consulted in regard to special points bearing on the relations between Korea and Japan.

A word must be said in regard to the authenticity and credibility of native Korean historical sources. The Chinese written character was introduced into Korea as a permanent factor about the time of Christ, and with it came the possibility of permanent historical records. That such records were kept is quite apparent from the fact that the dates of all solar eclipses have been carefully preserved from the year 57 B.C. In the next place it is worth noticing that the history of Korea is particularly free from those great cataclysms such as result so often in the destruction of libraries and records. Since the whole peninsula was consolidated under one flag in the days of ancient Sil-la no dynastic change has been effected by force. We have no mention of any catastrophe to the Sil-la records: and Sil-la merged into Koryŭ and Koryŭ into Cho-sŭn without the show of arms, and in each case the historical records were kept intact. To be sure, there have been three great invasions of Korea, by the Mongols, Manchus and Japanese respectively, but though much vandalism was committed by each of these, we have reason to believe that the records were not tampered with. The argument is three-fold. In the first place histories formed the great bulk of the literature in vogue among the people and it was so widely disseminated that it could not have been seriously injured without annihilating the entire population.

In the second place these invasions were made by peoples who, though not literary themselves, had a somewhat iiihigh regard for literature, and there could have been no such reason for destroying histories as might exist where one dynasty was forcibly ejected by another hostile one. In the third place the monasteries were the great literary centers during the centuries preceding the rise of the present dynasty, and we may well believe that the Mongols would not seriously molest these sacred repositories. On the whole then we may conclude that from the year 57 B.C. Korean histories are fairly accurate. Whatever comes before that is largely traditional and therefore more or less apocryphal.

One of the greatest difficulties encountered is the selection of a system of romanisation which shall steer a middle course between the Scilla of extreme accuracy and the Charybdis of extreme simplicity. I have adopted the rule of spelling all proper names in a purely phonetic way without reference to the way they are spelled in native Korean. In this way alone can the reader arrive at anything like the actual pronunciation as found in Korea. The simple vowels have their continental sounds: a as in “father,” i as in “ravine,” o as in “rope” and u as in “rule.” The vowel e is used only with the grave accent and is pronounced as in the French “recit.” When a vowel has the short mark over it, it is to be given the flat sound: ă as in “fat,” ŏ as in “hot,” ŭ as in “nut.” The umlaut ö is used but it has a slightly more open sound than in German. It is the “unrounded o” where the vowel is pronounced without protruding the lips. The pure Korean sound represented by oé is a pure diphthong and is pronounced by letting the lips assume the position of pronouncing o while the tongue is thrown forward as if to pronounce the short e in “met.” Eu is nearly the French eu but with a slightly more open sound. As for consonants they have their usual sounds, but when the surds k, p or t in the body of a word are immediately preceded by an open syllable or a syllable ending with a sonant, they change to their corresponding sonants: k to g, p to b and t to d. For instance, in the word Pak-tu, the t of the tu would be d if the first syllable were open. No word begins with the sonants g, b or d.

ivIn Korean we have the long and short quantity in vowels. Han may be pronounced either simply han or longer haan, but the distinction is not of enough importance to compensate for encumbering the system with additional diacritical marks.

In writing proper names I have adopted the plan most in use by sinologues. The patronymic stands alone and is followed by the two given names with a hyphen between them. All geographical names have hyphens between the syllables. To run the name all together would often lead to serious difficulty, for who would know, for instance, whether Songak were pronounced Son-gak or Song-ak?

In the spelling of some of the names of places there will be found to be a slight inconsistency because part of the work was printed before the Korea Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society had determined upon a system of romanization, but in the main the system here used corresponds to that of the Society.

This is the first attempt, so far as I am aware, to give to the English reading public a history of Korea based on native records, and I trust that in spite of all errors and infelicities it may add something to the general fund of information about the people of Korea.

H.B.H.

Seoul, Korea, 1905

Introductory Note

Geography is the canvas on which history is painted. Topography means as much to the historian as to the general. A word, therefore, about the position of Korea will not be out of place.

The peninsula of Korea, containing approximately 80,000 square miles, lies between 33° and 43° north latitude, and between 124° 30′ and 130° 30′ east longitude. It is about nine hundred miles long from north to south and has an average width from east to west of about 240 miles. It is separated from Manchuria on the northwest by the Yalu or Am-nok River, and from Asiatic Russia on the northeast by the Tu-man River. Between the sources of these streams rise the lofty peaks of White Head Mountain, called by the Chinese Ever-white or Long-white Mountain. From this mountain whorl emanates a range which passes irregularly southward through the peninsula until it loses itself in the waters of the Yellow Sea, thus giving birth to the almost countless islands of the Korean archipelago. The main watershed of the country is near the eastern coast and consequently the streams that flow into the Japan Sea are neither long nor navigable, while on the western side and in the extreme south we find considerable streams that are navigable for small craft a hundred miles or more. While the eastern coast is almost entirely lacking in good harbors the western coast is one labyrinth of estuaries, bays and gulfs which furnish innumerable harbors. It is on the western watershed of the country that we will find vimost of the arable land and by far the greater portion of the population.

We see then that, geographically, Korea’s face is toward China and her back toward Japan. It may be that this in part has moulded her history. During all the centuries her face has been politically, socially and religiously toward China rather than toward Japan.

The climate of Korea is the same as that of eastern North America between the same latitudes, the only difference being that in Korea the month of July brings the “rainy season” which renders nearly all roads in the interior impassable. This rainy season, by cutting in two the warmer portion of the year, has had a powerful influence on the history of the country; for military operations were necessarily suspended during this period and combatants usually withdrew to their own respective territories upon its approach.

The interior of Korea is fairly well wooded, although there are no very extensive tracts of timber land. A species of pine largely predominates but there is also a large variety of other trees both deciduous and evergreen.

Rice is the staple article of food throughout most of the country. Among the mountain districts in the north where rice cannot be grown potatoes and millet are largely used. An enormous amount of pulse is raised, almost solely for fodder, and other grains are also grown. The bamboo grows sparsely and only in the south. Ginseng is an important product of the country.

The fauna of Korea includes several species of deer, the tiger, leopard, wild pig, bear, wolf, fox and a large number of fur bearing animals among which the sable and sea-otter are the most valuable. The entire peninsula is thoroughly stocked with cattle, horses, swine and donkeys, but sheep are practically unknown. The fisheries off the coast of Korea are especially valuable and thousands of the people earn a livelihood on the banks. Pearls of good quality are found. Game birds of almost infinite variety exist and all the commoner domestic birds abound.

As to the geology of the country we find that there is viia back bone of granite formation with frequent outcroppings of various other forms of mineral life. Gold is extremely abundant and there are few prefectures in the country where traces of it are not found. Silver is also common. Large deposits of coal both anthracite and bituminous have been discovered, but until recently little has been done to open up the minerals of the country in a scientific manner.

Ethnologically we may say that the people are of a mixed Mongolian and Malay origin, although this question has as yet hardly been touched upon. The language of Korea is plainly agglutinative and may, without hesitation, be placed in the great Turanian or Scythian group.

The population of Korea is variously estimated from ten to twenty millions. We shall not be far from the truth if we take a middle course and call the population thirteen millions. Somewhat more than half of the people live south of a line drawn east and west through the capital of the country.

PART I

ANCIENT KOREA

Chapter I

Tan-gun.... his antecedents.... his origin.... he becomes king.... he teaches the people.... his capital.... he retires.... extent of his kingdom.... traditions.... monuments.

In the primeval ages, so the story runs, there was a divine being named Whan-in, or Che-Sŏ: “Creator.” His son, Whan-ung, being affected by celestial ennui, obtained permission to descend to earth and found a mundane kingdom. Armed with this warrant, Whan-ung with three thousand spirit companions descended upon Ta-băk Mountain, now known as Myo-hyang San, in the province of P’yŭng-an, Korea. It was in the twenty-fifth year of the Emperor Yao of China, which corresponds to 2332 B.C.

He gathered his spirit friends beneath the shade of an ancient pak-tal tree and there proclaimed himself King of the Universe. He governed through his three vice-regents, the “Wind General,” the “Rain Governor,” and the “Cloud Teacher,” but as he had not yet taken human shape, he found it difficult to assume control of a purely human kingdom. Searching for means of incarnation he found it in the following manner.

At early dawn, a tiger and a bear met upon a mountain side and held a colloquy.

“Would that we might become men” they said. Whan-ung overheard them and a voice came from out the void saying, “Here are twenty garlics and apiece of artemisia for each of you. Eat them and retire from the light of the sun for thrice seven days and you will become men.”

They ate and retired into the recesses of a cave, but the tiger, by reason of the fierceness of his nature, could not endure the restraint and came forth before the allotted time; but the bear, with greater faith and patience, waited the thrice seven days and then stepped forth, a perfect woman.

The first wish of her heart was maternity, and she cried, “Give me a son.” Whan-ung, the Spirit King, passing on the wind, beheld her sitting there beside the stream. He circled round her, breathed upon her, and her cry was answered. She cradled her babe in moss beneath that same pak-tal tree and it was there that in after years the wild people of the country found him sitting and made him their king.

This was the Tan-gun, “The Lord of the Pak-tal Tree.” He is also, but less widely, known as Wang-gŭm. At that time Korea and the territory immediately north was peopled by the “nine wild tribes” commonly called the Ku-i. Tradition names them respectively the Kyŭn, Pang, Whang, Făk, Chŭk, Hyŭn, P‘ung, Yang and U. These, we are told, were the aborigines, and were fond of drinking, dancing and singing. They dressed in a fabric of woven grass and their food was the natural fruits of the earth, such as nuts, roots, fruits and berries. In summer they lived beneath the trees and in winter they lived in a rudely covered hole in the ground. When the Tan-gun became their king he taught them the relation of king and subject, the rite of marriage, the art of cooking and the science of house building. He taught them to bind up the hair by tying a cloth about the head. He taught them to cut down trees and till fields.

The Tan-gun made P‘yŭng-yang the capital of his kingdom and there, tradition says, he reigned until the coming of Ki-ja, 1122 B.C. If any credence can be given this tradition it will be by supposing that the word Tan-gun refers to a line of native chieftains who may have antedated the coming of Ki-ja.

It is said that, upon the arrival of Ki-ja, the Tan-gun retired to Ku-wŭl San (in pure Korean A-sa-dal) in the present town of Mun-wha, Whang-hă Province, where he resumed his spirit form and disappeared forever from the earth. His wife was a woman of Pi-sŏ-ap, whose location is unknown. As to the size of the Tan-gun’s kingdom, it is generally believed that it extended from the vicinity of the present town of Mun-gyŭng on the south to the Heuk-yong River on the north, and from the Japan Sea on the east to Yo-ha (now Sŭng-gyŭng) on the west.

As to the events of the Tan-gun’s reign even tradition tells us very little. We learn that in 2265 B.C. the Tan-gun first offered sacrifice at Hyŭl-gu on the island of Kang-wha. For this purpose he built an altar on Mari San which remains to this day. We read that when the great Ha-u-si (The Great Yü), who drained off the waters which covered the interior of China, called to his court at To-san all the vassal kings, the Tan-gun sent his son, Pu-ru, as an envoy. This was supposed to be in 2187 B.C. Another work affirms that when Ki-ja came to Korea Pu-ru fled northward and founded the kingdom of North Pu-yŭ, which at a later date moved to Ka-yŭp-wŭn, and became Eastern Pu-yŭ. These stories show such enormous discrepancies in dates that they are alike incredible, and yet it may be that the latter story has some basis in fact, at any rate it gives us our only clue to the founding of the Kingdom of Pu-yŭ.

Late in the Tan-gun dynasty there was a minister named P‘ăng-o who is said to have had as his special charge the making of roads and the care of drainage. One authority says that the Emperor of China ordered P‘ăng-o to cut a road between Ye-măk, an eastern tribe, and Cho-sŭn. From this we see that the word Cho-sŭn, according to some authorities, antedates the coming of Ki-ja.

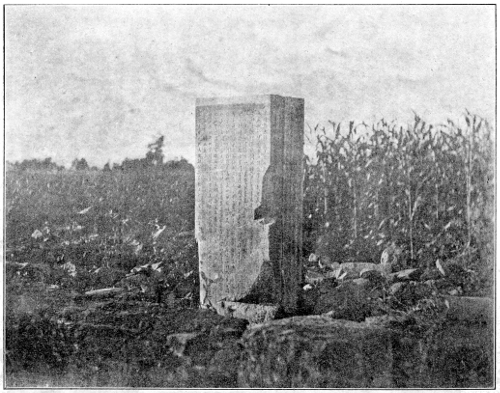

The remains of the Tan-gun dynasty, while not numerous, are interesting. On the island of Kang-wha, on the top of Mari San, is a stone platform or altar known as the “Tan-gun’s Altar,” and, as before said, it is popularly believed to have been used by the Tan-gun four thousand years ago. It is called also the Ch’am-sŭng Altar. On Chŭn-dung San is a fortress called Sam-nang which is believed to have been built by the Tan-gun’s three sons. The town of Ch’un-ch’ŭn, fifty miles east of Seoul, seems to have been an important place during this period. It was known as U-su-ju, or “Ox-hair Town,” and there is a curious confirmation of this tradition in the fact that in the vicinity there is today a plot of ground called the U-du-bol, or “Ox-head Plain.” A stone tablet to P’ang-o is erected there. At Mun-wha there is a shrine to the Korean trinity, Whan-in, Whan-ung and Tan-gun. Though the Tan-gun resumed the spirit form, his grave is shown in Kang-dong and is 410 feet in circumference.

Chapter II

Ki-ja.... striking character.... origin.... corrupt Chu.... story of Tal-geui.... Shang dynasty falls.... Ki-ja departs.... route.... destination.... allegience to China.... condition of Korea.... Ki-ja’s companions.... reforms.... evidences of genius.... arguments against Korean theory.... details of history meager.... Cho-sun sides against China.... delimitation of Cho-sun.... peace with Tsin dynasty.... Wi-man finds asylum.... betrays Cho-sun.... Ki-jun’s flight.

Without doubt the most striking character in Korean history is the sage Ki-ja, not only because of his connection with its early history but because of the striking contrast between him and his whole environment. The singular wisdom which he displayed is vouched for not in the euphemistic language of a prejudiced historian but by what we can read between the lines, of which the historian was unconscious.

The Shang, or Yin, dynasty of China began 1766 B.C. Its twenty-fifth representative was the Emperor Wu-yi whose second son, Li, was the father of Ki-ja. His family name was Cha and his surname Su-yu, but he is also known by the name Sö-yŭ. The word Ki-ja is a title meaning “Lord of Ki,” which we may imagine to be the feudal domain of the family. The Emperor Chu, the “Nero of China” and the last of the dynasty, was the grandson of Emperor T’ă-jŭng and a second cousin of Ki-ja, but the latter is usually spoken of as his uncle. Pi-gan, Mi-ja and Ki-ja formed the advisory board to this corrupt emperor.

All that Chinese histories have to say by way of censure against the hideous debaucheries of this emperor is repeated in the Korean histories; his infatuation with the beautiful concubine, Tal-geui; his compliance with her every whim; his making a pond of wine in which he placed an island of meat and compelled nude men and women to walk about it, his torture of innocent men at her request by tying them to heated brazen pillars. All this is told in the Korean annals, but they go still deeper into the dark problem of Tal-geui’s character and profess to solve it. The legend, as given by Korean tradition, is as follows.

The concubine Tal-geui was wonderfully beautiful, but surpassingly so when she smiled. At such times the person upon whom she smiled was fascinated as by a serpent and was forced to comply with whatever request she made. Pondering upon this, Pi-gan decided that she must be a fox in human shape, for it is well known that if an animal tastes of water that has lain for twenty years in a human skull it will acquire the power to assume the human shape at will. He set inquiries on foot and soon discovered that she made a monthly visit to a certain mountain which she always ascended alone leaving her train of attendants at the foot. Armed detectives were put on her track and, following her unperceived, they saw her enter a cave near the summit of the mountain. She presently emerged, accompanied by a pack of foxes who leaped about her and fawned upon her in evident delight. When she left, the spies entered and put the foxes to the sword, cutting from each dead body the piece of white fur which is always found on the breast of the fox. When Tal-geui met the emperor some days later and saw him dressed in a sumptuous white fur robe she shuddered but did not as yet guess the truth. A month later, however, it became plain to her when she entered the mountain cave and beheld the festering remains of her kindred.

On her way home she planned her revenge. Adorning herself in all her finery, she entered the imperial presence and exerted her power of fascination to the utmost. When the net had been well woven about the royal dupe, she said,

“I hear that there are seven orifices in the heart of every good man. I fain would put it to the test.”

“But how can it be done?”

“I would that I might see the heart of Pi-gan;” and as she said it she smiled upon her lord. His soul revolted from the act and yet he had no power to refuse. Pi-gan was summoned and the executioner stood ready with the knife, but at the moment when it was plunged into the victim’s breast he cried,

“You are no woman; you are a fox in disguise, and I charge you to resume your natural shape.”

Instantly her face began to change; hair sprang forth upon it, her nails grew long, and, bursting forth from her garments, she stood revealed in her true character—a white fox with nine tails. With one parting snarl at the assembled court, she leaped from the window and made good her escape.

But it was too late to save the dynasty. Pal, the son of Mun-wang, a feudal baron, at the head of an army, was already thundering at the gates, and in a few days, a new dynasty assumed the yellow and Pal, under the title Mu-wang, became its first emperor.

Pi-gan and Mi-ja had both perished and Ki-ja, the sole survivor of the great trio of statesmen, had saved his life only by feigning madness. He was now in prison, but Mu-wang came to his door and besought him to assume the office of Prime Minister. Loyalty to the fallen dynasty compelled him to refuse. He secured the Emperor’s consent to his plan of emigrating to Cho-sŭn or “Morning Freshness,” but before setting out he presented the Emperor with that great work, the Hong-bŭm or “Great-Law,” which had been found inscribed upon the back of the fabled tortoise which came up out of the waters of the Nak River in the days of Ha-u-si over a thousand years before, but which no one had been able to decipher till Ki-ja took it in hand. Then with his five thousand followers he passed eastward into the peninsula of Korea.

Whether he came to Korea by boat or by land cannot be certainly determined. It is improbable that he brought such a large company by water and yet one tradition says that he came first to Su-wŭn, which is somewhat south of Chemulpo. This would argue an approach by sea. The theory which has been broached that the Shantung promontory at one time joined the projection of Whang-hă Province on the Korean coast cannot be true, for the formation of the Yellow Sea must have been too far back in the past to help us to solve this question. It is said that from Su-wŭn he went northward to the island Ch’ŭl-do, off Whang-hă Province, where today they point out a “Ki-ja Well.” From there he went to P‘yŭng-yang. His going to an island off Whang-hă Province argues against the theory of the connection between Korea and the Shantung promontory.

In whatever way he came, he finally settled at the town of P‘yŭng-yang which had already been the capital of the Tan-gun dynasty. Seven cities claimed the honor of being Homer’s birth place and about as many claim to be the burial spot of Ki-ja. The various authorities differ so widely as to the boundaries of his kingdom, the site of his capital and the place of his interment that some doubt is cast even upon the existence of this remarkable man; but the consensus of opinion points clearly to P‘yŭng-yang as being the scene of his labors.

It should be noticed that from the very first Korea was an independent kingdom. It was certainly so in the days of the Tan-gun and it remained so when Ki-ja came, for it is distinctly stated that though the Emperor Mu-wang made him King of Cho-sŭn he neither demanded nor received his allegience as vassal at that time. He even allowed Ki-ja to send envoys to worship at the tombs of the fallen dynasty. It is said that Ki-ja himself visited the site of the ancient Shang capital, but when he found it sown with barley he wept and composed an elegy on the occasion, after which he went and swore allegience to the new Emperor. The work entitled Cho-sŏ says that when Ki-ja saw the site of the former capital sown with barley he mounted a white cart drawn by a white horse and went to the new capital and swore allegience to the Emperor; and it adds that in this he showed his weakness for he had sworn never to do so.

Ki-ja, we may believe, found Korea in a semi-barbarous condition. To this the reforms which he instituted give abundant evidence. He found at least a kingdom possessed of some degree of homogeneity, probably a uniform language and certainly ready communication between its parts. It is difficult to believe that the Tan-gun’s influence reached far beyond the Amnok River, wherever the nominal boundaries of his kingdom were. We are inclined to limit his actual power to the territory now included in the two provinces of P‘yŭng-an and Whang-hă.

We must now inquire of what material was Ki-ja’s company of five thousand men made up. We are told that he brought from China the two great works called the Si-jun and the So-jun, which by liberal interpretation mean the books on history and poetry. The books which bear these names were not written until centuries after Ki-ja’s time, but the Koreans mean by them the list of aphorisms or principles which later made up these books. It is probable, therefore, that this company included men who were able to teach and expound the principles thus introduced. Ki-ja also brought the sciences of manners (well named a science), music, medicine, sorcery and incantation. He brought also men capable of teaching one hundred of the useful trades, amongst which silk culture and weaving are the only two specifically named. When, therefore, we make allowance for a small military escort we find that five thousand men were few enough to undertake the carrying out of the greatest individual plan for colonization which history has ever seen brought to a successful issue.

These careful preparations on the part of the self-exiled Ki-ja admit of but one conclusion. They were made with direct reference to the people among whom he had elected to cast his lot. He was a genuine civilizer. His genius was of the highest order in that, in an age when the sword was the only arbiter, he hammered his into a pruning-hook and carved out with it a kingdom which stood almost a thousand years. He was the ideal colonizer, for he carried with him all the elements of successful colonization which, while sufficing for the reclamation of the semi-barbarous tribes of the peninsula, would still have left him self-sufficient in the event of their contumacy. His method was brilliant when compared with even the best attempts of modern times.

His penal code was short, and clearly indicated the failings of the people among whom he had cast his lot. Murder was to be punished with death inflicted in the same manner in which the crime had been committed. Brawling was punished by a fine to be paid in grain. Theft was punished by enslaving the offender, but he could regain his freedom by the payment of a heavy fine. There were five other laws which are not mentioned specifically. Many have surmised, and perhaps rightly, that they were of the nature of the o-hang or“five precepts” which inculcate right relations between king and subject, parent and child, husband and wife, friend and friend, old and young. It is stated, apocryphally however, that to prevent quarreling Ki-ja compelled all males to wear a broad-brimmed hat made of clay pasted on a framework. If this hat was either doffed or broken the offender was severely punished. This is said to have effectually kept them at arms length.