편집 요약 없음 |

편집 요약 없음 |

||

| 852번째 줄: | 852번째 줄: | ||

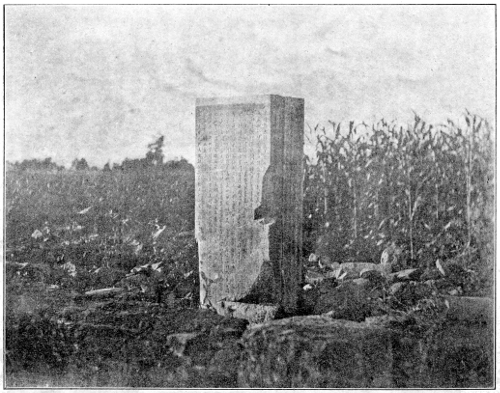

[[파일:SILLA BOUNDARY STONE.jpg|500픽셀|섬네일|가운데]] | [[파일:SILLA BOUNDARY STONE.jpg|500픽셀|섬네일|가운데]] | ||

The last act in the tragedy of Ko-gu-ryŭ opens with the death of her iron chancellor, Hap So-mun. It was his genius that had kept the armies in the field; it was his faith in her ultimate victory that had kept the general courage up. When he was laid in his grave the only thing that Ko-gu-ryŭ had to fall back upon was the energy of despair. It was her misfortune that Hap So-mun left two sons each of whom possessed a full share of his father’s ferocity and impatience of restraint. Nam-săng, the elder, assumed his father’s position as Prime Minister, but while he was away in the country attending to some business, his brother, Nam-gŭn, seized his place. Nam-săng fled to the Yalu River and putting himself at the head of the Mal-gal and Kŭ-ran tribes went over with them to the Emperor’s side. Thus by Nam-gŭn’s treachery to his brother, Ko-gu-ryŭ was deprived of her one great ally, and gained an implacable enemy in Nam-săng. The Emperor made the latter Governor-general of Liao-tung and he began welding the wild tribes into an instrument for revenge. Then the Chinese forces appeared and together they went to the feast of death; and even as they were coming news reached them that the Ko-gu-ryŭ general, Yŭn Chŭn-t‘o, had surrendered to Sil-la and turned over to her twelve of Ko-gu-ryŭ’s border forts. It was not till the next year that the Chinese crossed the Liao and fell upon the Ko-gu-ryŭ outposts. The Chinese general had told his men that the strategic point was the fortress Sin-sŭng and that its capture meant the speedy capitulation of all the rest. Sin-sŭng was therefore besieged and the struggle began. The commandant was loyal and wished to defend it to the death but his men thought otherwise, and they bound him and surrendered. Then sixteen other forts speedily followed the example. | |||

Gen. Ko-gan hastened forward and engaged the Ko-gu-ryŭ forces at Keum-san and won a decided victory, while at the same time Gen. Sŭl-In gwi was reducing the fortresses of Nam-so, Mok-jŭ and Ch‘ang-am, after which he was joined by the Mal-gal forces under the renegade Nam-săng. Another Chinese general, Wŭn Man-gyŭng, now sent a boastful letter to the 112Ko-gu-ryŭ capital saying “Look out now for the defenses of that precious Am-nok River of yours.” The answer came grimly back “We will do so.” And they did it so well that not a Chinese soldier set foot on the hither side during that year. The Emperor was enraged at this seeming incompetence and banished the boastful general to Yong-nam. A message had already been sent to Sil-la ordering her to throw her army into Ko-gu-ryŭ and for the Chinese generals Yu In-wŭn and Kim In-t‘ă to meet them before P‘yŭng-yang. These two generals were in Păk-je at the time. | |||

In 668 everything beyond the Yalu had fallen into the hands of the Chinese; even Pu-yŭ Fortress of ancient fame had been taken by Gen. Sŭl In-gwi. The Emperor sent a messenger asking “Can you take Ko-gu-ryŭ?” The answer went back “Yes, we must take her. Prophecy says that after 700 years Ko-gu-ryŭ shall fall and that eighty shall cause her overthrow. The 700 years have passed and now Gen. Yi Jök is eighty years old. He shall be the one to fulfill the prophecy.” | |||

Terrible omens had been seen in the Ko-gu-ryŭ capital. Earthquakes had been felt; foxes had been seen running through the streets; the people were in a state of panic. The end of Ko-gu-ryŭ was manifestly near. So tradition says. | |||

Nam-gŭn had sent 50,000 troops to succor Pu-yŭ Fortress but in the battle which ensued 30,000 of these were killed and the remainder were scattered. Conformably to China’s demands, Sil-la in the sixth moon threw her army into Ko-gu-ryŭ. The great Sil-la general, Kim Yu-sin was ill, and so Gen. Kim In-mun was in command with twenty-eight generals under him. While this army was making its way northward the Chinese under Gen. Yi Jök in the north took Tă-hăng Fortress and focussed all the troops in his command upon the defenses of the Yalu. These defenses were broken through, the river was crossed and the Chinese advanced 210 li toward the capital without opposition. One by one the Ko-gu-ryŭ forts surrendered and at last Gen. Kye-p‘il Ha-ryŭk arrived before the historic city of P‘yŭng-yang. Gen. Yi Jök arrived next and finally Gen. Kim In-mun appeared at the head of the Sil-la army. | |||

After an uninteresting siege of a month the king sent out 113Gen. Chön Nam-san and ninety other nobles with a flag of truce and offered to surrender. But the chancellor Nam-gŭn knew what fate was in store for him, so he made a bold dash at the besieging army. The attempt failed and the miserable man put the sword to his own throat and expired. The aged general, Yi Jök, took the king and his two sons, Pong-nam, and Tong-nam, a number of the officials, many of Nam-gŭn’s relatives and a large company of the people of P‘yŭng-yang and carried them back to China, where he was received with evidences of the utmost favor by the Emperor. The whole number of captives in the triumphal return of Gen. Yi Jök is said to have been 20,000. | |||

Ko-gu-ryŭ’s lease of life had been 705 years, from 37 B.C. to 668 A.D., during which time she had been governed by twenty-eighty kings. | |||

Chapter XIII. | |||

Sil-la’s captives.... Ko-gu-ryŭ dismembered.... extent of Sil-la.... she deceives China.... her encroachments.... rebellion.... the word Il-bon (Nippon) adopted.... Sil-la opposed China.... but is humbled.... again opposes.... Sil-la a military power.... her policy.... the Emperor nominates a rival king.... Sil-la pardoned by China.... again makes trouble.... the Emperor establishes two kingdoms in the north.... Sil-la’s northern capital.... cremation.... no mention of Arabs.... China’s interest in Korea wanes.... redistribution of land.... diacritical points.... philological interest.... Pal-hă founded.... Chinese customs introduced.... Pal-hă’s rapid growth.... omens.... Sil-la’s northern limit.... casting of a bell.... names of provinces changed.... Sil-la’s weakness.... disorder.... examinations.... Buddhism interdicted.... no evidence of Korean origin of Japanese Buddhism.... Japanese history before the 10th century.... civil wars.... Ch‘oé Ch‘i-wŭn.... tradition.... Queen Man’s profligacy. | |||

Immediately upon the fall of Ko-gu-ryŭ the Sil-la forces retired to their own country carrying 7000 captives with them. The king gave his generals and the soldiers rich presents of silks and money. | |||

China divided all Ko-gu-ryŭ into nine provinces in which there were forty-two large towns and over a hundred lesser ones of prefectural rank. In P‘yŭng-yang Gen. Sŭl In-gwi 114was stationed with a garrison of 20,000 men. The various provinces were governed partly by Chinese governors and partly by native prefects. | |||

The king of Sil-la was now the only king in the peninsula and the presumption was that in view of his loyalty to the Chinese his kingdom would extend to the Yalu River if not beyond, but it probably was not extended at the time further than the middle of Whang-hă Province of to-day. The records say that in 669 the three kingdoms were all consolidated but it did not occur immediately. It is affirmed that the Chinese took 38,000 families from Ko-gu-ryŭ and colonized Kang-whe in China and that some were also sent to San-nam in western China. That Sil-la was expecting a large extension of territory is not explicitly stated but it is implied in the statement that when a Sil-la envoy went to the Chinese court the Emperor accused the king of wanting to possess himself of the whole peninsula, and threw the envoy into prison. At the same time he ordered Sil-la to send bow-makers to China to make bows that would shoot 1,000 paces. In due time these arrived but when the bows were made it was found that they would shoot but thirty paces. They gave as a reason for this that it was necessary to obtain the wood from Sil-la to make good bows. This was done and still the bows would shoot but sixty paces. The bow-makers declared that they did not know the reason unless it was because the wood had been hurt by being brought across the water. This was the beginning of an estrangement between the Emperor and the king of Sil-la which resulted in a state of actual war between the two. | |||

Sil-la was determined to obtain possession of a larger portion of Ko-gu-ryŭ than had as yet fallen to her lot; so she sent small bodies of troops here and there to take possession of any districts that they could lay their hands on. It is probable that this meant only such districts as were under native prefects and not those under direct Chinese rule. It is probable that Sil-la had acquired considerable territory in the north for we are told that the Mal-gal ravaged her northern border and she sent troops to drive them back. | |||

If China hoped to rule any portion of Korea without trouble she must have been speedily disillusionised for no sooner had the new form of government been put in operation 115than a Sil-la gentleman, Köm Mo-jam, raised an insurrection in one of the larger magistracies, put the Chinese prefect to death and proclaimed An Seung king. He was a member of a collateral branch of the royal family. Sil-la seems to have taken it for granted that the whole territory was under her supervision for now she sent an envoy and gave consent to the founding of this small state in the north which she deemed would act as a barrier to the incursions of the northern barbarians. The Chinese evidently did not look upon it in this light and a strong force was sent against the nascent state; and to such effect that the newly appointed king fled to Sil-la for safety. The wheel of fortune was turning again and Chinese sympathies were now rather with Păk-je than with Sil-la. | |||

It was at this time, 671, that the term Il-bün (Nippon) was first used in Korea in connection with the kingdom of Japan. | |||

The relations between Sil-la and Păk-je were badly strained. In the following year the Chinese threw a powerful army into Păk-je with the evident intention of opposing Sil-la. So the latter furbished up her arms and went into the fray. In the great battle which ensued at the fortress of Sŭk-sŭng 5,000 of the Chinese were killed. Sil-la was rather frightened at her own success and when she was called upon to explain her hostile attitude toward China she averred that it was all a mistake and she did not intend to give up her allegience to China. This smoothed the matter over for the time being, but when, a little later, the Emperor sent seventy boat loads of rice for the garrison at P‘yŭng-yang, Sil-la seized the rice and drowned the crew’s of the boats, thus storing up wrath against herself. The next year she attacked the fortress of Ko-sŭng in Păk-je and 30,000 Chinese advanced to the support of the Păk-je forces. A collision took place between them and the Sil-la army in which the Chinese were very severely handled. This made the Emperor seriously consider the question of subduing Sil-la once for all. He ordered that the Mal-gal people be summoned to a joint invasion of the insolent Sil-la and the result was that seven Sil-la generals were driven back in turn and 2,000 troops made prisoners. In this predicament there was nothing for the king to do but play the humble suppliant again. The letter to the Emperor praying for pardon 116was written by the celebrated scholar Im Gang-su. But it was not successful, for we find that in the following year the Chinese troops in the north joined with the Mal-gal and Kŭ-ran tribes in making reprisals on Sil-la territory. This time however Sil-la was on the alert and drove the enemy back with great loss. She also sent a hundred war boats up the western coast to look after her interests in the north. At the same time she offered amnesty and official positions to Păk-je nobles who should come over to her side. | |||

We can scarcely escape the conviction that Sil-la had now become a military power of no mean dimensions. Many citizens of Ko-gu-ryŭ had come over to her and some of the Păk-je element that was disaffected toward the Chinese. All, in fact, who wanted to keep Korea for the Koreans and could put aside small prejudices and jealousies, gathered under the Sil-la banners as being the last chance of saving the peninsula from the octopus grasp of China. Sil-la was willing to be good friends with China—on her own terms; namely that China should let her have her own way in the peninsula, and that it should not be overrun by officious generals who considered themselves superior to the king of the land and so brought him into contempt among the people. | |||

At this time there was at the Chinese court a Sil-la envoy of high rank named Kim In-mun. The Emperor offered him the throne of Sil-la, but loyalty to his king made him refuse the honor. In spite of this he was proclaimed King of Sil-la and was sent with three generals to enforce the claim. That Sil-la was not without power at this time is shown by the fact that she proclaimed An-seung King of Păk-je, an act that would have been impossible had she not possessed a strong foothold in that country. | |||

The war began again in earnest. The Chinese general, Yi Gön-hăng, in two fierce encounters, broke the line of Sil-la defenses and brought the time-serving king to his knees again. One can but wonder at the patience of the Emperor in listening to the humble petition of this King Mun-mu who had made these promises time and again but only to break them as before. He was, however, forgiven and confirmed again in his rule. The unfortunate Kim In-mun whom the Emperor had proclaimed King of Sil-la was now in a very delicate position 117and he wisely hastened back to China where he was compensated for his disappointment by being made a high official. | |||

Sil-la’s actions were most inconsistent, for having just saved herself from condign punishment by abject submission she nevertheless kept on absorbing Păk-je territory and reaching after Ko-gu-ryŭ territory as well. In view of this the Emperor ordered the Chinese troops in the north to unite with the Mal-gal and Kŭ-ran forces and hold themselves in readiness to move at an hour’s notice. They began operations by attacking the Chön-sŭng Fortress but there the Sil-la forces were overwhelmingly successful. It is said that 6,000 heads fell and that Sil-la captured 30,000 (?) horses. This is hard to reconcile with the statement of the records that in the following year a Sil-la envoy was received at the Chinese court and presented the compliments of the king. It seems sure that Sil-la had now so grown in the sinews of war that it was not easy for China to handle her at such long range. It may be too that the cloud of Empress Wu’s usurpation had begun to darken the horizon of Chinese politics and that events at home absorbed all the attention of the court, while the army on the border was working practically on its own authority. | |||

A new kind of attempt to solve the border question was made when in 677 the Emperor sent the son of the captive king of Ko-gu-ryŭ to found a little kingdom on the Yalu River. This might be called the Latter Ko-gu-ryŭ even as the Păk-je of that day was called the Latter Păk-je. At the same time a son of the last Păk-je king was sent to found a little kingdom at Tă-bang in the north. He lived, however, in fear of the surrounding tribes and was glad to retire into the little Ko-gu-ryŭ kingdom that lay lower down the stream. The records call this the “last” end of Păk-je. | |||

In 678 Sil-la made a northern capital at a place called Puk-wŭn-ju the capital of Kang-wŭn Province. There a fine palace was erected. The king enquired of his spiritual adviser whether he had better change his residence to the new capital but not receiving sufficient encouragement he desisted. This monarch died in 681 but before he expired he said “Do not waste the public money in building me a costly mausoleum. Cremate my body after the manner of the West.” This gives us an interesting clue to Sil-la’s knowledge of the 118outside world. If, as some surmise, Arab traders had commercial intercourse with the people of Sil-la it must have been about this time or a little earlier for this was the period of the greatest expansion of Arabian commerce. It is possible that the idea of cremation may have been received from them although from first to last there is not the slightest intimation that Western traders ever visited the coasts of Sil-la. It is difficult to believe that, had there been any considerable dealings with the Arabs, it should not have been mentioned in the records. | |||

The king’s directions were carried out and his son, Chong-myŭng, burned his body on a great stone by the Eastern Sea and gave the stone the name “Great King Stone.” That the Emperor granted investiture to this new king shows that all the troubles had been smoothed over. But from this time on Chinese interest in the Korean peninsula seems to have died out altogether. The little kingdom of Latter Ko-gu-ryŭ, which the Emperor had established on the border, no sooner got on a sound basis than it revolted and the Emperor had to stamp it out and banish its king to a distant Chinese province. This, according to the records, was the “last” end of Ko-gu-ryŭ. It occurred in 682 A.D. | |||

Sil-la now held all the land south of the Ta-dong River. North of that the country was nominally under Chinese control but more likely was without special government. In 685 Sil-la took in hand the redistribution of the land and the formation of provinces and prefectures for the purpose of consolidating her power throughout the peninsula. She divided the territory into nine provinces, making three of the original Păk-je and three of that portion of the original Ko-gu-ryŭ that had fallen into her hands. The three provinces corresponding to the original Sil-la were (1) Sŭ-bŭl-ju (the first step in the transformation of the word Sŭ ya-bŭl to Seoul), (2) Sam-yang-ju, now Yang-san, (3) Ch‘ŭng-ju now Chin-ju. Those comprising the original Păk-je were (1) Ung-ch‘ŭn-ju in the north, (2) Wan-san-ju in the south-west, (3) Mu-jin-ju in the south, now Kwang-ju. Of that portion of Ko-gu-ryŭ which Sil-la had acquired she made the three provinces (1) Han-san-ju, now Seoul, (2) Mok-yak-ju, now Ch‘un-ch‘ŭn, (3) Ha-să-ju, now Kang-neung. These nine names 119represent rather the provincial capitals than the provinces themselves. Besides these important centers there were 450 prefectures. Changes followed each other in quick succession. Former Ko-gu-ryŭ officials were given places of trust and honor; the former mode of salarying officials, by giving them tracts of land from whose produce they obtained their emoluments, was changed, and each received an allowance of rice according to his grade; the administration of the state was put on a solid basis. | |||

One of the most far-reaching and important events of this reign was the invention of the yi-du, or set of terminations used in the margin of Chinese texts to aid the reader in Koreanizing the syntax of the Chinese sentence. We must bear in mind that in those days reading was as rare an accomplishment in Sil-la as it was in England in the days of Chaucer. All writing was done by the a-jun, who was the exact counterpart of the “clerk” of the Middle Ages. The difficulty of construing the Chinese sentence and using the right suffixes was so great that Sŭl-ch‘ong, the son of the king’s favorite monk, Wŭn-hyo, attempted a solution of the difficulty. Making a list of the endings in common use in the vernacular of Sil-la he found Chinese characters to correspond with the sounds of these endings. The correspondence was of two kinds; either the name of the Chinese character was the same as the Sil-la ending or the Sil-la meaning of the character was the same as the ending. To illustrate this let us take the case of the ending sal-ji, as in ha-sal-ji, which has since been shortened to ha-ji. Now, in a Chinese text nothing but the root idea of the word ha will be given and the reader must supply the sal-ji which is the ending. If then some arbitrary signs could be made to represent these endings and could be put in the margin it would simplify the reading of Chinese in no small degree. It was done in this way: There is a Chinese character which the Koreans call păk, Chinese pa, meaning “white.” One of the Sil-la definitions of this character sal-wi-ta. It was the first syllable of this word that was used to represent the first syllable of the ending sal-ji. Notice that it was not the name of the character that was used but the Sil-la equivalent. For the last syllable of the ending sal-ji, however, the Chinese character ji is used without reference to its 120Sil-la equivalent. We find then in the yi-du as handed down from father to son by the a-jun’s of Korea a means for discovering the connection between the Korean vernacular of to-day with that of the Sil-la people. It was indeed a clumsy method, but the genius of Sŭl-ch‘ong lay in his discovery of the need of such a system and of the possibility of making one. It was a literary event of the greatest significance. It was the first outcry against the absurd primitiveness of the Chinese ideography, a plea for common sense. It was the first of three great protests which Korea has made against the use of the Chinese character. The other two will be examined as they come up. This set of endings which Sŭl-ch‘ong invented became stereotyped and through all the changes which the vernacular has passed the yi-du remains to-day what it was twelve hundred years ago. Its quaint sounds are to the Korean precisely what the stereotyped clerkly terms of England are to us, as illustrated in such legal terms as to wit, escheat and the like. There is an important corollary to this fact. The invention of the yi-du indicates that the study of Chinese was progressing in the peninsula and this system was invented to supply a popular demand. It was in the interests of general education and as such marks an era in the literary life of the Korean people. The name of Sŭl-ch‘ong is one of the most honored in the list of Korean literary men. | |||

The eighth century opened with the beginning of a new and important reign for Sil-la. Sŭng-dŭk came to the throne in 702 and was destined to hold the reins of power for thirty-five years. From the first, his relations with China were pleasant. He received envoys from Japan and returned the compliment, and his representatives were everywhere well received. The twelfth year of his reign beheld the founding of the kingdom of Pal-hă in the north. This was an event of great significance to Sil-la. The Song-mal family of the Mal-gal group of tribes, under the leadership of Kŭl-gŭl Chung-sŭng, moved southward into the peninsula and settled near the original Tă-băk Mountain, now Myo-hyang San. There they gathered together many of the Ko-gu-ryŭ people and founded a kingdom which they called Chin. It is said this kingdom was 5,000 li in circumference and that it contained 200,000 houses. The remnants of the Pu-yŭ and Ok-jŭ tribes 121joined them and a formidable kingdom arose under the skillful management of Kŭl-gŭl Chung-sŭng. He sent his son to China as a hostage and received imperial recognition and the title of King of Pal-hă. From that time the word Mal-gal disappears from Korean history and Pal-hă takes its place. | |||

During the next few years Sil-la made steady advance in civilization of the Chinese type. She imported from China pictures of Confucius and paid increased attention to that cult. The water clock was introduced, the title Hu was given to the Queen, the custom of approaching the throne by means of the sang-so or “memorial” was introduced. | |||

Meanwhile the kingdom of Pal-hă was rapidly spreading abroad its arms and grasping at everything in sight. China began to grow uneasy on this account and we find that in 734 a Sil-la general, Kim Yun-jung went to China and joined a Chinese expedition against the Pal-hă forces. The latter had not only absorbed much territory in the north but had dared to throw troops across the Yellow Sea and had gained a foothold on the Shantung promontory. This attempt to chastise her failed because the season was so far advanced that the approach of winter interfered with the progress of the campaign. | |||

The story of the next century and a half is the story of Sil-la’s decline and fall. The following is the list of omens which tradition cites as being prophetic of that event. A white rainbow pierced the sun; the sea turned to blood; hail fell of the size of hens’ eggs; a monastery was shaken sixteen times by an earthquake; a cow brought forth five calves at a time; two suns arose together; three stars fell and fought together in the palace; a tract of land subsided fifty feet and the hollow filled with blue black water; a tiger came into the palace; a black fog covered the land; famines and plagues were common; a hurricane blew over two of the palace gates; a huge boulder rose on end and stood by itself; two pagodas at a monastery fought with each other; snow fell in September; at Han-yang (Seoul) a boulder moved a hundred paces all by itself; stones fought with each other; a shower of worms fell; apricot trees bloomed twice in a year; a whirlwind started from the grave of Kim Yu-sin and stopped at the 122grave of Hyŭk Kŭ-se. These omens were scattered through a series of years but to the Korean they all point toward the coming catastrophe. | |||

It was in 735 that the Emperor formally invested the king of Sil-la with the right to rule as far north as the banks of the Ta-dong River which runs by the wall of P‘yŭng-yang. It was a right he had long exercised but which had never before been acquiesced in by China. The custom of cremating the royal remains, which had been begun by King Mun-mu, was continued by his successors and in each case the ashes were thrown into the sea. | |||

The first mention of the casting of a bell in Korea was in the year 754 when a bell one and one third the height of a man was cast. The records say it weighed 497,581 pounds, which illustrates the luxuriance of the oriental imagination. | |||

In 757 the names of the nine provinces were changed. Sŭ-bŭl became Sang-ju, Sam-yang became Yang-ju, Ch’ŭng-ju became Kang-ju, Han-san became Han-ju, Ha-să became Myŭng-ju, Ung-chŭn became Ung-ju, Wan-san became Chŭn-ju, Mu-jin became Mu-ju, and Su-yak (called Mok-yak in the other list) was changed to Sak-ju. Following hard upon this came the change of the name of government offices. | |||

As we saw at the first, Sil-la never had in her the making of a first class power. Circumstances forced her into the field and helped her win, and for a short time the enthusiasm of success made her believe that she was a military power; but it was an illusion. She was one of those states which would flourish under the fostering wing of some great patron but as for standing alone and carving out a career for herself, that was beyond her power. Only a few years had passed since she had taken possession of well-nigh the whole of the peninsula and now we see her torn by internal dissentions and so weak that the first man of power who arose and shook his sword at her doors made her fall to pieces like a house of cards. Let us rapidly bring under review the events of the next century from 780 to 880 and see whether the facts bear out the statement. | |||

First a conspiracy was aimed at the king and was led by a courtier named Kim Chi-jong. Another man, Yang Sang, learned of it and promptly seized him and put him to death. 123A very meritorious act one would say; but he did it in order to put his foot upon the same ladder, for he immediately turned about and killed the king and queen and seated himself upon the throne. His reign of fifteen years contains only two important events, the repeopling of P‘yŭng-yang with citizens of Han-yang (Seoul), and the institution of written examinations after the Chinese plan. In 799 Chun-ong came to the throne and was followed a year later by his adopted son Ch‘ŭng-myŭng. These two reigns meant nothing to Sil-la except the reception of a Japanese envoy bearing gifts and an attempt at the repression of Buddhism. The building of monasteries and the making of gold and silver Buddhas was interdicted. It is well to remember that in all these long centuries no mention is made of a Korean envoy to Japan, though Japanese envoys came not infrequently to Sil-la. There is no mention in the records of any request on the part of the Japanese for Buddhist books or teachers and there seems to be no evidence from the Korean standpoint to believe that Japan received her Buddhism from Korea. Geographically it would seem probable that she might have done so but as a fact there is little to prove it. It would, geographically speaking, be probable also that Japan would get her pronunciation of the Chinese character by way of Korea but as a matter of fact the two methods of the pronunciation of Chinese ideographs are at the very antipodes. The probability is that Japan received her knowledge both of Buddhism and of the Chinese character direct from China and not mainly by way of Korea. | |||

The condition of Sil-la during this period of decline may be judged from the events which occurred between the years 836 and 839 inclusive. King Su-jong was on the throne and had been ruling some eleven years, when, in 835 he died and his cousin Kyun-jăng succeeded him. Before the year was out Kim Myŭng a powerful official put him to death and put Che Yung on the throne. The son of the murdered king, Yu-jeung, fled to Ch‘ŭng-hă Fortress, whither many loyal soldiers flocked around him and enabled him to take the field against the usurper. Kim Myu finding that affairs did not go to suit him killed the puppet whom he had put on the throne and elevated himself to that position. After Yu-jeung, the rightful heir, had received large reinforcements from various 124sources, he attacked the forces of this parvenu at Mu-ju and gained a victory. The young prince followed up this success by a sharp attack on the self-made king who fled for his life but was pursued and captured. Yu-jeung then ascended the throne. This illustrates the weakness of the kingdom, in that any adventurer, with only daring and nerve, could seize the seat of power and hold it even so long as Kim Myŭng did. The outlying provinces practically governed themselves. There was no power of direction, no power to bring swift punishment upon disloyal adventurers, and the whole attitude of the kingdom invited insubordination. In this reign there were two other rebellions which had to be put down. | |||

The year 896 shows a bright spot in a dark picture. The celebrated scholar Ch‘oé Ch‘i-wŭn appeared upon the scene. He was born in Sa-ryang. At the age of twelve he went to China to study; at eighteen he obtained a high literary degree at the court of China. He travelled widely and at last returned to his native land where his erudition and statesmanship found instant recognition. He was elevated to a high position and a splendid career lay before him; but he was far ahead of his time; one of those men who seem to have appeared a century or two before the world was ready for them. The low state of affairs at the court of Sil-la is proved by the intense hatred and jealousy which he unwittingly aroused. He soon found it impossible to remain in office; so he quietly withdrew to a mountain retreat and spent his time in literary pursuits. His writings are to be found in the work entitled Ko-un-jip. He is enshrined in the memory of Koreans as the very acme of literary attainment, the brightest flower of Sil-la civilization and without a superior in the annals of all the kingdoms of the peninsula. | |||

Tradition asserts that signs began to appear and portents of the fall of Sil-la. King Chung-gang made a journey through the southern part of the country and returned by boat. A dense fog arose which hid the land. Sacrifice was offered to the genius of the sea, and the fog lifted and a strange and beautiful apparition of a man appeared who accompanied the expedition back to the capital and sang a song whose burden was that many wise men would die and that the capital would be changed. Chung-gang died the next year and was succeeded 125by his brother Chin-sung who lived but a year and then made way for his sister who became the ruler of the land. Her name was Man. Under her rule the court morals fell to about as low a point as was possible. When her criminal intimacy with a certain courtier, Eui-hong, was terminated by the death of the latter she took three or four other lovers at once, raising them to high offices in the state and caring as little for the real welfare of the country as she did for her own fair fame. Things reached such a pass that the people lost patience with her and insulting placards were hung in the streets of the capital calling attention to the depth of infamy to which the court had sunk. | |||

It was in 892 that the great bandit Yang-gil arose in the north. His right hand man was Kung-ye, and as he plays an important part in the subsequent history of Sil-la we must stop long enough to give his antecedents. The story of his rise is the story of the inception of the Kingdom of Ko-ryŭ. It may be proper to close the ancient history of Korea at this point and begin the medieval section with the events which led up to the founding of Koryŭ. | |||

=PART II. MEDIEVAL KOREAN HISTORY= | |||

From 890 to 1392 A.D. | |||

Chapter I. | |||

Kung-ye.... antecedents.... revolts.... Ch‘oé Ch‘i-wŭn.... retires.... Wang-gön.... origin.... Kung-ye successful.... advances Wang-gön himself King.... Wang-gön again promoted.... Sil-la court corrupt.... Kung-ye proclaims himself a Buddha.... condition of the peninsula.... Wang-gön accused.... refuses the throne.... forced to take it.... Kung-ye killed.... prophecy.... Wang-gön does justice..... Ko-ryŭ organized..... Buddhist festival..... Song-do.... Ko-ryŭ’s defenses.... Kyŭn-whŭn becomes Wang-gön’s enemy.... wild tribes submit.... China upholds Kyŭn-whŭn.... his gift to Wang-gön.... loots the capital of Sil-la.... Ko-ryŭ troops repulsed.... war.... Wang-gön visits Sil-la.... improvements.... Kyŭn-whŭn’s last stand.... imprisoned by his sons.... comes to Song-do.... Sil-la expires.... her last king comes to Song-do.... Wang-gön’s generosity. | |||

Kung-ye was the son of King Hön-gang by a concubine. He was born on the least auspicious day of the year, the fifth of the fifth moon. He had several teeth when he was born which made his arrival the less welcome. The King ordered the child to be destroyed; so it was thrown out of the window. But the nurse rescued it and carried it to a place of safety where she nursed it and provided for its bringing up. As she was carrying the child to this place of safety she accidentally put out one of its eyes. When he reached man’s estate he became a monk under the name of Sŭn-jong. He was by nature ill fitted for the monastic life and soon found himself in the camp of the bandit Ki-whŭn at Chuk-ju. Soon he began to consider himself ill-treated by his new master and deserted him, finding his way later to the camp of the bandit Yang-gil at Puk-wŭn now Wŭn-ju. A considerable number of men accompanied 128him. Here his talents were better appreciated and he was put in command of a goodly force with which he soon overcame the districts of Ch‘un-ch‘ŭn, Nă-sŭng, Ul-o and O-jin. From this time Kung-ye steadily gained in power until he quite eclipsed his master. Marching into the western part of Sil-la he took ten districts and went into permanent camp. | |||

The following year another robber, Kyŭn-whŭn, made head against Sil-la in the southern part of what is now Kyŭng-sang Province. He was a Sang-ju man. Having seized the district of Mu-ju he proclaimed himself King of Southern Sil-la. His name was originally Yi but when fifteen years of age he had changed it to Kyŭn. He had been connected with the Sil-la army and had risen step by step and made himself extremely useful by his great activity in the field. When, however, the state of Sil-la became so corrupt as to be a by-word among all good men, he threw off his allegiance to her, gathered about him a band of desperate criminals, outlaws and other disaffected persons and began the conquest of the south and west. In a month he had a following of 5,000 men. He found he had gone too far in proclaiming himself King and so modified his title to that of “Master of Men and Horses.” It is said of him that once, while still a small child, his father being busy in the fields and his mother at work behind the house, a tiger came along and the child sucked milk from its udder. This accounted for his wild and fierce nature. | |||

At this time the great scholar Ch‘oé Ch‘i-wŭn, whom we have mentioned, was living at of Pu-sŭng. Recognizing the abyss of depravity into which the state was falling he formulated ten rules for the regulation of the government and sent them to Queen Man. She read and praised them but took no means to put them in force. Ch‘oé could no longer serve a Queen who made light of the counsels of her most worthy subjects and, throwing up his position, retired to Kwang-ju in Nam-san and became a hermit. After that he removed to Ping-san in Kang-ju, then to Ch‘ŭng-yang Monastery in Hyŭp-ju, then to Sang-gye Monastery at Ch‘i-ri San but finally made his permanent home at Ka-ya San where he lived with a few other choice spirits. It was here that he wrote his autobiography in thirteen volumes. | |||

129In 896 Kung-ye began operating in the north on a larger scale. He took ten districts near Ch‘ŭl-wŭn and put them in charge of his young lieutenant Wang-gön who was destined to become the founder of a dynasty. We must now retrace our steps in order to tell of the origin of this celebrated man. | |||

Wang-yŭng, a large-minded and ambitious man, lived in the town of Song-ak. To him a son was born in the third year of King Hön-gang of Sil-la, A.D. 878. The night the boy was born a luminous cloud stood above the house and made it as bright as day, so the story runs. The child had a very high forehead and a square chin, and he developed rapidly. His birth had long since been prophesied by a monk named To-sŭn who told Wang-yŭng, as he was building his house, that within its walls a great man would be born. As the monk turned to go Wang-yŭng called him back and received from him a letter which he was ordered to give to the yet unborn child when he should be old enough to read. The contents are unknown but when the boy reached his seventeenth year the same monk reappeared and became his tutor, instructing him especially in the art of war. He showed him also how to obtain aid from the heavenly powers, how to sacrifice to the spirits of mountain and stream so as to propitiate them. Such is the tradition that surrounds the origin of the youth who now in the troubled days of Sil-la found a wide field for the display of his martial skill. | |||

Kung-ye first ravaged the country from Puk-wŭn to A-sil-la, with 600 followers. He there assumed the title of “Great General.” Then he reduced all the country about Nang-ch’ŭn, Han-san, Kwan-nă and Ch‘ŭl-wŭn. By this time his force had enormously increased and his fame had spread far and wide. All the wild tribes beyond the Ta-dong River did obeisance to him. But these successes soon began to turn his head. He styled himself “Prince” and began to appoint prefects to various places. He advanced Wang-gön to a high position and made him governor of Song-do. This he did at the instigation of Wang-yŭng who sent him the following enigmatical advice: “If you want to become King of Cho-sŭn, Suk-sin and Pyön-han you must build a wall about Song-do and make my son governor.” It was immediately done, and in this way Wang-gön was provided with a place for his capital. | |||

130In 897 the profligate Queen Man of Sil-la handed the government over to her adopted son Yo and retired. This change gave opportunities on every side for the rebels to ply their trade. Kung-ye forthwith seized thirty more districts north of the Han River and Kyŭn-whŭn established his headquarters at Wan-san, now Chŭn-ju and called his kingdom New Păk-je. Wang-gön, in the name of Kung-ye, seized almost the whole of the territory included in the present provinces of Kyŭng-geui and Ch‘ung-ch‘ŭng. Finally in 901 Kung-ye proclaimed himself king and emphasized it by slashing with a sword the picture of the king of Sil-la which hung in a monastery. Two years later Wang-gön moved southward into what is now Chŭl-la Province and soon came in contact with the forces of Kyŭn-whŭn. In these contests the young Wang-gön was uniformly successful. | |||

In 905 Kung-ye established his capital at Ch‘ŭl-wŭn in the present Kang-wŭn province and named his kingdom Ma-jin and the year was called Mut. Then he distributed the offices among his followers. By this time all the north and east had joined the standards of Kung-ye and Wang-gön even to within 120 miles of the Sil-la capital. The king and court of Sil-la were in despair. There was no army with which to take the field and all they could do was to defend the position they had as best they could and hope that Kyung-ye and Kyŭn-whŭn might destroy each other. In 909 Kung-ye called Sil-la “The Kingdom to be Destroyed” and set Wang-gön as military governor of all the south-west. Here he pursued an active policy, now fitting out ships with which to subjugate the neighboring islands and now leading the attack on Kyŭn-whŭn who always suffered in the event. His army was a model of military precision and order. Volunteers flocked to his standard. He was recognised as the great leader of the day. When, at last, Na-ju fell into the hands of the young Wang-gön, Kyŭn-whŭn decided on a desperate venture and suddenly appearing before that town laid siege to it. After ten days of unsuccessful assault he retired but Wang-gön followed and forced an engagement at Mok-p‘o, now Yŭng-san-p‘o, and gave him such a whipping that he was fain to escape alone and unattended. | |||

Meanwhile Kung-ye’s character was developing. Cruelty 131and capriciousness became more and more his dominant qualities. Wang-gön never acted more wisely than in keeping as far as possible from the court of his master. His rising fame would have instantly roused the jealousy of Kung-ye. | |||

Sil-la had apparently adopted the principle “Let us eat and be merry for to-morrow we die.” Debauchery ran rife at the court and sapped what little strength was left. Among the courtiers was one of the better stamp and when he found that the king preferred the counsel of his favorite concubine to his own, he took occasion to use a sharper argument in the form of a dagger, which at a blow brought her down from her dizzy eminence. | |||

In 911 Kung-ye changed the name of his kingdom to Tă-bong. It is probable that this was because of a strong Buddhistic tendency that had at this time quite absorbed him. He proclaimed himself a Buddha, called himself Mi-ryŭk-pul, made both his sons Buddhists, dressed as a high priest and went nowhere without censers. He pretended to teach the tenets of Buddhism. He printed a book, and put a monk to death because he did not accept it as canonical. The more Kung-ye dabbled in Buddhism the more did all military matters devolve upon Wang-gön, who from a distance beheld with amazement and concern the dotage of his master. At his own request he was always sent to a post far removed from the court. At last Kung-ye became so infatuated that he seemed little better than a madman. He heated an iron to a white heat and thrust it into his wife’s womb because she continually tried to dissuade him from his Buddhistic notions. He charged her with being an adultress. He followed this up by killing both his sons and many other of the people near his person. He was hated as thoroughly as he was feared. | |||

The year 918 was one of the epochal years of Korean history. The state of the peninsula was as follows. In the south-east, the reduced kingdom of Sil-la, prostrated by her own excesses, without an army, and yet in her very supineness running to excess of riot, putting off the evil day and trying to drown regrets in further debauchery. In the central eastern portion, the little kingdom of Kung-ye who had now become a tyrant and a madman. He had put his whole army under the hand of a young, skillful, energetic and popular man who had 132gained the esteem of all classes. In the south-west was another sporadic state under Kyŭn-whŭn who was a fierce, unscrupulous bandit, at swords points with the rising Wang-gön. | |||

Suddenly Kung-ye awoke to the reality of his position. He knew he was hated by all and that Wang-gön was loved by all, and he knew too that the army was wholly estranged from himself and that everything depended upon what course the young general should pursue. Fear, suspicion and jealousy mastered him and he suddenly ordered the young general up to the capital. Wang-gön boldly complied, knowing doubtless by how slender a thread hung his fortunes. When he entered his master’s presence the latter exclaimed “You conspired against me yesterday.” The young man calmly asked how. Kung-ye pretended to know it through the power of his sacred office as Buddha. He said “Wait, I will again consult the inner consciousness.” Bowing his head he pretended to be communing with his inner self. At this moment one of the clerks purposely dropped his pen, letting it roll near to the prostrate form of Wang-gön. As the clerk stooped to pick it up, he whispered in Wang-gön’s ear “Confess that you have conspired.” The young man grasped the situation at once. When the mock Buddha raised his head and repeated the accusation Wang-gön confessed that it was true. The King was delighted at this, for he deceived himself into believing that he actually had acquired the faculty of reading men’s minds. This pleased him so greatly that he readily forgave the offence and merely warned the young man not to repeat it. After this he gave Wang-gön rich gifts and had more confidence in him than ever. | |||

But the officials all besieged the young general with entreaties to crush the cruel and capricious monarch and assume the reins of government himself. This he refused to do, for through it all, he was faithful to his master. But they said “He has killed his wife and his sons and we will all fall a prey to his fickle temper unless you come to our aid. He is worse than the Emperor Chu.” Wang-gön, however, urged that it was the worst of crimes to usurp a throne. “But” said they “is it not much worse for us all to perish? If one does not improve the opportunity that heaven provides it is a sin.” He was unmoved by this casuistry and stood his ground firmly. 133At last even his wife joined in urging him to lay aside his foolish scruples and she told the officials to take him by force and carry him to the palace, whether he would or not. They did so, and bearing him in their arms they burst through the palace gate and called upon the wretch Kung-ye to make room for their chosen king. The terrified creature fled naked but was caught at Pu-yang, now P‘yŭng-gang, and beheaded. | |||

Tradition says that this was all in fulfillment of a prophecy which was given in the form of an enigma. A Chinese merchant bought a mirror of a Sil-la man and in the mirror could be seen these words: “Between three waters—God sends his son to Chin and Ma—First seize a hen and then a duck—in the year Ki-ja two dragons will arise, one in a green forest and one east of black metal.” The merchant presented it to Kung-ye who prized it highly and sought everywhere for the solution of the riddle. At last the scholar Song Han-hong solved it for him as follows. “The Chin and Ma mean Chin-han and Ma-han. The hen is Kye-rim (Sil-la). The duck is the Am-nok (duck-blue) River. The green forest is pine tree or Song-do (Pine Tree Capital) and black metal is Ch‘ŭl-wŭn (Ch‘ŭl is metal). So a king in Song-do must arise (Wang-gön) and a king in Ch‘ŭl-wŭn must fall (Kung-ye).” | |||

Wang-gön began by bringing to summary justice the creatures of Kung-ye who seconded him in his cruelty; some of them were killed and some were imprisoned. Everywhere the people gave themselves up to festivities and rejoicings. | |||

But the ambitious general, Whan Son-gil, took advantage of the unsettled state of affairs to raise an insurrection. Entering the palace with a band of desperadoes he suddenly entered the presence of Wang-gön who was without a guard. The King rose from his seat, and looking the traitor in the face said “I am not King by my own desire or request. You all made me King. It was heaven’s ordinance and you cannot kill me. Approach and try.” The traitor thought that the King had a strong guard secreted near by and turning fled from the palace. He was caught and beheaded. | |||

Wang-gön sent messages to all the bandit chiefs and invited them to join the new movement, and soon from all sides they came in and swore allegiance to the young king. Kyŭn-whŭn, however, held aloof and sought for means to put down 134the new power. Wang-gön set to work to establish his kingdom on a firm basis. He changed the official system and established a new set of official grades. He rewarded those who had been true to him and remitted three years’ revenues. He altered the revenue laws, requiring the people to pay much less than heretofore, manumitted over a thousand slaves and gave them goods out of the royal storehouses with which to make a start in life. As P‘yŭng-yang was the ancient capital of the country he sent one of the highest officials there as governor. And he finished the year with a Buddhist festival, being himself a Buddhist of a mild type. This great annual festival is described as follows:—There was an enormous lantern, hung about with hundreds of others, under a tent made of a net-work of silk cords. Music was an important element. There were also representations of dragons, birds, elephants, horses, carts and boats. Dancing was prominent and there were in all a hundred forms of entertainment. Each official wore the long flowing sleeves and each carried the ivory memo tablet. The king sat upon a high platform and watched the entertainment. | |||

The next year he transferred his court to Song-do which became the permanent capital. There he built his palace and also the large merchants’ houses and shops in the center of the city. This latter act was in accordance with the ancient custom of granting a monopoly of certain kinds of trade and using the merchants as a source of revenue when a sudden need for money arose. He divided the city into five wards and established seven military stations. He also established a secondary capital at Ch‘ŭl-wŭn, the present Ch‘un-ch‘ŭn, and called it Tong-ju. The pagodas and Buddhas in both the capitals were regilded and put in good order. The people looked with some suspicion upon these Buddhistic tendencies but he told them that the old customs must not be changed too rapidly, for the kingdom had need of the help of the spirits in order to become thoroughly established, and that when that was accomplished they could abandon the religion as soon as they pleased. Here was his grand mistake. He riveted upon the state a baneful influence which was destined to drag it into the mire and eventually bring it to ruin. | |||

In 920 Sil-la first recognised Koryŭ as a kingdom 135and sent an envoy with presents to the court at Song-do. | |||

2023년 2월 18일 (토) 14:31 판

이 책은 Project Gutenberg의 일환으로 제작된 ebook으로 저작권이 없습니다.

HOMER B. HULBERT, A.M., F.R.G.S.

Seoul, 1905

The Methodist Publishing House

Preface

The sources from which the following History of Korea is drawn are almost purely Korean. For ancient and medieval history the Tong-sa Kang-yo has been mainly followed. This is an abstract in nine volumes of the four great ancient histories of the country. The facts here found were verified by reference to the Tong-guk Tong-gam, the most complete of all existing ancient histories of the country. Many other works on history, geography and biography have been consulted, but in the main the narrative in the works mentioned above has been followed.

A number of Chinese works have been consulted, especially the Mun-hon Tong-go wherein we find the best description of the wild tribes that occupied the peninsula about the time of Christ.

It has been far more difficult to obtain material for compiling the history of the past five centuries. By unwritten law the history of no dynasty in Korea has ever been published until after its fall. Official records are carefully kept in the government archives and when the dynasty closes these are published by the new dynasty. There is an official record which is published under the name of the Kuk-cho Po-gam but it can in no sense be called a history, for it can contain nothing that is not complimentary to the ruling house and, moreover, it has not been brought down even to the opening of the 19th century. It has been necessary therefore to find private iimanuscript histories of the dynasty and by uniting and comparing them secure as accurate a delineation as possible of the salient features of modern Korean history. In this I have enjoyed the services of a Korean scholar who has made the history of this dynasty a special study for the past twenty-five years and who has had access to a large number of private manuscripts. I withhold his name by special request. By special courtesy I have also been granted access to one of the largest and most complete private libraries in the capital. Japanese records have also been consulted in regard to special points bearing on the relations between Korea and Japan.

A word must be said in regard to the authenticity and credibility of native Korean historical sources. The Chinese written character was introduced into Korea as a permanent factor about the time of Christ, and with it came the possibility of permanent historical records. That such records were kept is quite apparent from the fact that the dates of all solar eclipses have been carefully preserved from the year 57 B.C. In the next place it is worth noticing that the history of Korea is particularly free from those great cataclysms such as result so often in the destruction of libraries and records. Since the whole peninsula was consolidated under one flag in the days of ancient Sil-la no dynastic change has been effected by force. We have no mention of any catastrophe to the Sil-la records: and Sil-la merged into Koryŭ and Koryŭ into Cho-sŭn without the show of arms, and in each case the historical records were kept intact. To be sure, there have been three great invasions of Korea, by the Mongols, Manchus and Japanese respectively, but though much vandalism was committed by each of these, we have reason to believe that the records were not tampered with. The argument is three-fold. In the first place histories formed the great bulk of the literature in vogue among the people and it was so widely disseminated that it could not have been seriously injured without annihilating the entire population.

In the second place these invasions were made by peoples who, though not literary themselves, had a somewhat iiihigh regard for literature, and there could have been no such reason for destroying histories as might exist where one dynasty was forcibly ejected by another hostile one. In the third place the monasteries were the great literary centers during the centuries preceding the rise of the present dynasty, and we may well believe that the Mongols would not seriously molest these sacred repositories. On the whole then we may conclude that from the year 57 B.C. Korean histories are fairly accurate. Whatever comes before that is largely traditional and therefore more or less apocryphal.

One of the greatest difficulties encountered is the selection of a system of romanisation which shall steer a middle course between the Scilla of extreme accuracy and the Charybdis of extreme simplicity. I have adopted the rule of spelling all proper names in a purely phonetic way without reference to the way they are spelled in native Korean. In this way alone can the reader arrive at anything like the actual pronunciation as found in Korea. The simple vowels have their continental sounds: a as in “father,” i as in “ravine,” o as in “rope” and u as in “rule.” The vowel e is used only with the grave accent and is pronounced as in the French “recit.” When a vowel has the short mark over it, it is to be given the flat sound: ă as in “fat,” ŏ as in “hot,” ŭ as in “nut.” The umlaut ö is used but it has a slightly more open sound than in German. It is the “unrounded o” where the vowel is pronounced without protruding the lips. The pure Korean sound represented by oé is a pure diphthong and is pronounced by letting the lips assume the position of pronouncing o while the tongue is thrown forward as if to pronounce the short e in “met.” Eu is nearly the French eu but with a slightly more open sound. As for consonants they have their usual sounds, but when the surds k, p or t in the body of a word are immediately preceded by an open syllable or a syllable ending with a sonant, they change to their corresponding sonants: k to g, p to b and t to d. For instance, in the word Pak-tu, the t of the tu would be d if the first syllable were open. No word begins with the sonants g, b or d.

ivIn Korean we have the long and short quantity in vowels. Han may be pronounced either simply han or longer haan, but the distinction is not of enough importance to compensate for encumbering the system with additional diacritical marks.

In writing proper names I have adopted the plan most in use by sinologues. The patronymic stands alone and is followed by the two given names with a hyphen between them. All geographical names have hyphens between the syllables. To run the name all together would often lead to serious difficulty, for who would know, for instance, whether Songak were pronounced Son-gak or Song-ak?

In the spelling of some of the names of places there will be found to be a slight inconsistency because part of the work was printed before the Korea Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society had determined upon a system of romanization, but in the main the system here used corresponds to that of the Society.

This is the first attempt, so far as I am aware, to give to the English reading public a history of Korea based on native records, and I trust that in spite of all errors and infelicities it may add something to the general fund of information about the people of Korea.

H.B.H.

Seoul, Korea, 1905

Introductory Note

Geography is the canvas on which history is painted. Topography means as much to the historian as to the general. A word, therefore, about the position of Korea will not be out of place.

The peninsula of Korea, containing approximately 80,000 square miles, lies between 33° and 43° north latitude, and between 124° 30′ and 130° 30′ east longitude. It is about nine hundred miles long from north to south and has an average width from east to west of about 240 miles. It is separated from Manchuria on the northwest by the Yalu or Am-nok River, and from Asiatic Russia on the northeast by the Tu-man River. Between the sources of these streams rise the lofty peaks of White Head Mountain, called by the Chinese Ever-white or Long-white Mountain. From this mountain whorl emanates a range which passes irregularly southward through the peninsula until it loses itself in the waters of the Yellow Sea, thus giving birth to the almost countless islands of the Korean archipelago. The main watershed of the country is near the eastern coast and consequently the streams that flow into the Japan Sea are neither long nor navigable, while on the western side and in the extreme south we find considerable streams that are navigable for small craft a hundred miles or more. While the eastern coast is almost entirely lacking in good harbors the western coast is one labyrinth of estuaries, bays and gulfs which furnish innumerable harbors. It is on the western watershed of the country that we will find vimost of the arable land and by far the greater portion of the population.

We see then that, geographically, Korea’s face is toward China and her back toward Japan. It may be that this in part has moulded her history. During all the centuries her face has been politically, socially and religiously toward China rather than toward Japan.

The climate of Korea is the same as that of eastern North America between the same latitudes, the only difference being that in Korea the month of July brings the “rainy season” which renders nearly all roads in the interior impassable. This rainy season, by cutting in two the warmer portion of the year, has had a powerful influence on the history of the country; for military operations were necessarily suspended during this period and combatants usually withdrew to their own respective territories upon its approach.

The interior of Korea is fairly well wooded, although there are no very extensive tracts of timber land. A species of pine largely predominates but there is also a large variety of other trees both deciduous and evergreen.

Rice is the staple article of food throughout most of the country. Among the mountain districts in the north where rice cannot be grown potatoes and millet are largely used. An enormous amount of pulse is raised, almost solely for fodder, and other grains are also grown. The bamboo grows sparsely and only in the south. Ginseng is an important product of the country.

The fauna of Korea includes several species of deer, the tiger, leopard, wild pig, bear, wolf, fox and a large number of fur bearing animals among which the sable and sea-otter are the most valuable. The entire peninsula is thoroughly stocked with cattle, horses, swine and donkeys, but sheep are practically unknown. The fisheries off the coast of Korea are especially valuable and thousands of the people earn a livelihood on the banks. Pearls of good quality are found. Game birds of almost infinite variety exist and all the commoner domestic birds abound.

As to the geology of the country we find that there is viia back bone of granite formation with frequent outcroppings of various other forms of mineral life. Gold is extremely abundant and there are few prefectures in the country where traces of it are not found. Silver is also common. Large deposits of coal both anthracite and bituminous have been discovered, but until recently little has been done to open up the minerals of the country in a scientific manner.

Ethnologically we may say that the people are of a mixed Mongolian and Malay origin, although this question has as yet hardly been touched upon. The language of Korea is plainly agglutinative and may, without hesitation, be placed in the great Turanian or Scythian group.

The population of Korea is variously estimated from ten to twenty millions. We shall not be far from the truth if we take a middle course and call the population thirteen millions. Somewhat more than half of the people live south of a line drawn east and west through the capital of the country.

PART I ANCIENT KOREA

Chapter I

Tan-gun.... his antecedents.... his origin.... he becomes king.... he teaches the people.... his capital.... he retires.... extent of his kingdom.... traditions.... monuments.

In the primeval ages, so the story runs, there was a divine being named Whan-in, or Che-Sŏ: “Creator.” His son, Whan-ung, being affected by celestial ennui, obtained permission to descend to earth and found a mundane kingdom. Armed with this warrant, Whan-ung with three thousand spirit companions descended upon Ta-băk Mountain, now known as Myo-hyang San, in the province of P’yŭng-an, Korea. It was in the twenty-fifth year of the Emperor Yao of China, which corresponds to 2332 B.C.

He gathered his spirit friends beneath the shade of an ancient pak-tal tree and there proclaimed himself King of the Universe. He governed through his three vice-regents, the “Wind General,” the “Rain Governor,” and the “Cloud Teacher,” but as he had not yet taken human shape, he found it difficult to assume control of a purely human kingdom. Searching for means of incarnation he found it in the following manner.

At early dawn, a tiger and a bear met upon a mountain side and held a colloquy.

“Would that we might become men” they said. Whan-ung overheard them and a voice came from out the void saying, “Here are twenty garlics and apiece of artemisia for each of you. Eat them and retire from the light of the sun for thrice seven days and you will become men.”

They ate and retired into the recesses of a cave, but the tiger, by reason of the fierceness of his nature, could not endure the restraint and came forth before the allotted time; but the bear, with greater faith and patience, waited the thrice seven days and then stepped forth, a perfect woman.

The first wish of her heart was maternity, and she cried, “Give me a son.” Whan-ung, the Spirit King, passing on the wind, beheld her sitting there beside the stream. He circled round her, breathed upon her, and her cry was answered. She cradled her babe in moss beneath that same pak-tal tree and it was there that in after years the wild people of the country found him sitting and made him their king.

This was the Tan-gun, “The Lord of the Pak-tal Tree.” He is also, but less widely, known as Wang-gŭm. At that time Korea and the territory immediately north was peopled by the “nine wild tribes” commonly called the Ku-i. Tradition names them respectively the Kyŭn, Pang, Whang, Făk, Chŭk, Hyŭn, P‘ung, Yang and U. These, we are told, were the aborigines, and were fond of drinking, dancing and singing. They dressed in a fabric of woven grass and their food was the natural fruits of the earth, such as nuts, roots, fruits and berries. In summer they lived beneath the trees and in winter they lived in a rudely covered hole in the ground. When the Tan-gun became their king he taught them the relation of king and subject, the rite of marriage, the art of cooking and the science of house building. He taught them to bind up the hair by tying a cloth about the head. He taught them to cut down trees and till fields.

The Tan-gun made P‘yŭng-yang the capital of his kingdom and there, tradition says, he reigned until the coming of Ki-ja, 1122 B.C. If any credence can be given this tradition it will be by supposing that the word Tan-gun refers to a line of native chieftains who may have antedated the coming of Ki-ja.

It is said that, upon the arrival of Ki-ja, the Tan-gun retired to Ku-wŭl San (in pure Korean A-sa-dal) in the present town of Mun-wha, Whang-hă Province, where he resumed his spirit form and disappeared forever from the earth. His wife was a woman of Pi-sŏ-ap, whose location is unknown. As to the size of the Tan-gun’s kingdom, it is generally believed that it extended from the vicinity of the present town of Mun-gyŭng on the south to the Heuk-yong River on the north, and from the Japan Sea on the east to Yo-ha (now Sŭng-gyŭng) on the west.

As to the events of the Tan-gun’s reign even tradition tells us very little. We learn that in 2265 B.C. the Tan-gun first offered sacrifice at Hyŭl-gu on the island of Kang-wha. For this purpose he built an altar on Mari San which remains to this day. We read that when the great Ha-u-si (The Great Yü), who drained off the waters which covered the interior of China, called to his court at To-san all the vassal kings, the Tan-gun sent his son, Pu-ru, as an envoy. This was supposed to be in 2187 B.C. Another work affirms that when Ki-ja came to Korea Pu-ru fled northward and founded the kingdom of North Pu-yŭ, which at a later date moved to Ka-yŭp-wŭn, and became Eastern Pu-yŭ. These stories show such enormous discrepancies in dates that they are alike incredible, and yet it may be that the latter story has some basis in fact, at any rate it gives us our only clue to the founding of the Kingdom of Pu-yŭ.

Late in the Tan-gun dynasty there was a minister named P‘ăng-o who is said to have had as his special charge the making of roads and the care of drainage. One authority says that the Emperor of China ordered P‘ăng-o to cut a road between Ye-măk, an eastern tribe, and Cho-sŭn. From this we see that the word Cho-sŭn, according to some authorities, antedates the coming of Ki-ja.

The remains of the Tan-gun dynasty, while not numerous, are interesting. On the island of Kang-wha, on the top of Mari San, is a stone platform or altar known as the “Tan-gun’s Altar,” and, as before said, it is popularly believed to have been used by the Tan-gun four thousand years ago. It is called also the Ch’am-sŭng Altar. On Chŭn-dung San is a fortress called Sam-nang which is believed to have been built by the Tan-gun’s three sons. The town of Ch’un-ch’ŭn, fifty miles east of Seoul, seems to have been an important place during this period. It was known as U-su-ju, or “Ox-hair Town,” and there is a curious confirmation of this tradition in the fact that in the vicinity there is today a plot of ground called the U-du-bol, or “Ox-head Plain.” A stone tablet to P’ang-o is erected there. At Mun-wha there is a shrine to the Korean trinity, Whan-in, Whan-ung and Tan-gun. Though the Tan-gun resumed the spirit form, his grave is shown in Kang-dong and is 410 feet in circumference.

Chapter II

Ki-ja.... striking character.... origin.... corrupt Chu.... story of Tal-geui.... Shang dynasty falls.... Ki-ja departs.... route.... destination.... allegience to China.... condition of Korea.... Ki-ja’s companions.... reforms.... evidences of genius.... arguments against Korean theory.... details of history meager.... Cho-sun sides against China.... delimitation of Cho-sun.... peace with Tsin dynasty.... Wi-man finds asylum.... betrays Cho-sun.... Ki-jun’s flight.

Without doubt the most striking character in Korean history is the sage Ki-ja, not only because of his connection with its early history but because of the striking contrast between him and his whole environment. The singular wisdom which he displayed is vouched for not in the euphemistic language of a prejudiced historian but by what we can read between the lines, of which the historian was unconscious.

The Shang, or Yin, dynasty of China began 1766 B.C. Its twenty-fifth representative was the Emperor Wu-yi whose second son, Li, was the father of Ki-ja. His family name was Cha and his surname Su-yu, but he is also known by the name Sö-yŭ. The word Ki-ja is a title meaning “Lord of Ki,” which we may imagine to be the feudal domain of the family. The Emperor Chu, the “Nero of China” and the last of the dynasty, was the grandson of Emperor T’ă-jŭng and a second cousin of Ki-ja, but the latter is usually spoken of as his uncle. Pi-gan, Mi-ja and Ki-ja formed the advisory board to this corrupt emperor.

All that Chinese histories have to say by way of censure against the hideous debaucheries of this emperor is repeated in the Korean histories; his infatuation with the beautiful concubine, Tal-geui; his compliance with her every whim; his making a pond of wine in which he placed an island of meat and compelled nude men and women to walk about it, his torture of innocent men at her request by tying them to heated brazen pillars. All this is told in the Korean annals, but they go still deeper into the dark problem of Tal-geui’s character and profess to solve it. The legend, as given by Korean tradition, is as follows.

The concubine Tal-geui was wonderfully beautiful, but surpassingly so when she smiled. At such times the person upon whom she smiled was fascinated as by a serpent and was forced to comply with whatever request she made. Pondering upon this, Pi-gan decided that she must be a fox in human shape, for it is well known that if an animal tastes of water that has lain for twenty years in a human skull it will acquire the power to assume the human shape at will. He set inquiries on foot and soon discovered that she made a monthly visit to a certain mountain which she always ascended alone leaving her train of attendants at the foot. Armed detectives were put on her track and, following her unperceived, they saw her enter a cave near the summit of the mountain. She presently emerged, accompanied by a pack of foxes who leaped about her and fawned upon her in evident delight. When she left, the spies entered and put the foxes to the sword, cutting from each dead body the piece of white fur which is always found on the breast of the fox. When Tal-geui met the emperor some days later and saw him dressed in a sumptuous white fur robe she shuddered but did not as yet guess the truth. A month later, however, it became plain to her when she entered the mountain cave and beheld the festering remains of her kindred.

On her way home she planned her revenge. Adorning herself in all her finery, she entered the imperial presence and exerted her power of fascination to the utmost. When the net had been well woven about the royal dupe, she said,

“I hear that there are seven orifices in the heart of every good man. I fain would put it to the test.”

“But how can it be done?”

“I would that I might see the heart of Pi-gan;” and as she said it she smiled upon her lord. His soul revolted from the act and yet he had no power to refuse. Pi-gan was summoned and the executioner stood ready with the knife, but at the moment when it was plunged into the victim’s breast he cried,

“You are no woman; you are a fox in disguise, and I charge you to resume your natural shape.”

Instantly her face began to change; hair sprang forth upon it, her nails grew long, and, bursting forth from her garments, she stood revealed in her true character—a white fox with nine tails. With one parting snarl at the assembled court, she leaped from the window and made good her escape.

But it was too late to save the dynasty. Pal, the son of Mun-wang, a feudal baron, at the head of an army, was already thundering at the gates, and in a few days, a new dynasty assumed the yellow and Pal, under the title Mu-wang, became its first emperor.

Pi-gan and Mi-ja had both perished and Ki-ja, the sole survivor of the great trio of statesmen, had saved his life only by feigning madness. He was now in prison, but Mu-wang came to his door and besought him to assume the office of Prime Minister. Loyalty to the fallen dynasty compelled him to refuse. He secured the Emperor’s consent to his plan of emigrating to Cho-sŭn or “Morning Freshness,” but before setting out he presented the Emperor with that great work, the Hong-bŭm or “Great-Law,” which had been found inscribed upon the back of the fabled tortoise which came up out of the waters of the Nak River in the days of Ha-u-si over a thousand years before, but which no one had been able to decipher till Ki-ja took it in hand. Then with his five thousand followers he passed eastward into the peninsula of Korea.

Whether he came to Korea by boat or by land cannot be certainly determined. It is improbable that he brought such a large company by water and yet one tradition says that he came first to Su-wŭn, which is somewhat south of Chemulpo. This would argue an approach by sea. The theory which has been broached that the Shantung promontory at one time joined the projection of Whang-hă Province on the Korean coast cannot be true, for the formation of the Yellow Sea must have been too far back in the past to help us to solve this question. It is said that from Su-wŭn he went northward to the island Ch’ŭl-do, off Whang-hă Province, where today they point out a “Ki-ja Well.” From there he went to P‘yŭng-yang. His going to an island off Whang-hă Province argues against the theory of the connection between Korea and the Shantung promontory.

In whatever way he came, he finally settled at the town of P‘yŭng-yang which had already been the capital of the Tan-gun dynasty. Seven cities claimed the honor of being Homer’s birth place and about as many claim to be the burial spot of Ki-ja. The various authorities differ so widely as to the boundaries of his kingdom, the site of his capital and the place of his interment that some doubt is cast even upon the existence of this remarkable man; but the consensus of opinion points clearly to P‘yŭng-yang as being the scene of his labors.

It should be noticed that from the very first Korea was an independent kingdom. It was certainly so in the days of the Tan-gun and it remained so when Ki-ja came, for it is distinctly stated that though the Emperor Mu-wang made him King of Cho-sŭn he neither demanded nor received his allegience as vassal at that time. He even allowed Ki-ja to send envoys to worship at the tombs of the fallen dynasty. It is said that Ki-ja himself visited the site of the ancient Shang capital, but when he found it sown with barley he wept and composed an elegy on the occasion, after which he went and swore allegience to the new Emperor. The work entitled Cho-sŏ says that when Ki-ja saw the site of the former capital sown with barley he mounted a white cart drawn by a white horse and went to the new capital and swore allegience to the Emperor; and it adds that in this he showed his weakness for he had sworn never to do so.

Ki-ja, we may believe, found Korea in a semi-barbarous condition. To this the reforms which he instituted give abundant evidence. He found at least a kingdom possessed of some degree of homogeneity, probably a uniform language and certainly ready communication between its parts. It is difficult to believe that the Tan-gun’s influence reached far beyond the Amnok River, wherever the nominal boundaries of his kingdom were. We are inclined to limit his actual power to the territory now included in the two provinces of P‘yŭng-an and Whang-hă.

We must now inquire of what material was Ki-ja’s company of five thousand men made up. We are told that he brought from China the two great works called the Si-jun and the So-jun, which by liberal interpretation mean the books on history and poetry. The books which bear these names were not written until centuries after Ki-ja’s time, but the Koreans mean by them the list of aphorisms or principles which later made up these books. It is probable, therefore, that this company included men who were able to teach and expound the principles thus introduced. Ki-ja also brought the sciences of manners (well named a science), music, medicine, sorcery and incantation. He brought also men capable of teaching one hundred of the useful trades, amongst which silk culture and weaving are the only two specifically named. When, therefore, we make allowance for a small military escort we find that five thousand men were few enough to undertake the carrying out of the greatest individual plan for colonization which history has ever seen brought to a successful issue.