편집 요약 없음 |

|||

| (같은 사용자의 중간 판 66개는 보이지 않습니다) | |||

| 4번째 줄: | 4번째 줄: | ||

대한제국멸망사 | 대한제국멸망사 | ||

[[헐버트|HOMER B. HULBERT]] | |||

New York 1906 | New York 1906 | ||

| 14번째 줄: | 14번째 줄: | ||

theme from a more intimate standpoint than that of the casual | theme from a more intimate standpoint than that of the casual | ||

tourist. | tourist. | ||

| 20번째 줄: | 21번째 줄: | ||

directly from Koreans or from Korean works. Some of this matter | directly from Koreans or from Korean works. Some of this matter | ||

has already appeared in The Korea Review and elsewhere. The | has already appeared in The Korea Review and elsewhere. The | ||

historical survey is a condensation from the writer's | historical survey is a condensation from the writer's "[[The History of Korea|History of | ||

Korea. | Korea]] | ||

". | |||

| 47번째 줄: | 49번째 줄: | ||

NEW YORK, 1906. | NEW YORK, 1906. | ||

=INTRODUCTORY= | =INTRODUCTORY= | ||

There is a peculiar pathos in the extinction of a | There is a peculiar pathos in the extinction of a | ||

nation. Especially is this true when the nation is | nation. Especially is this true when the nation is | ||

| 302번째 줄: | 305번째 줄: | ||

will here find a narrative of the course of events which led up | will here find a narrative of the course of events which led up | ||

to this crisis, and the part that different powers, including the | to this crisis, and the part that different powers, including the | ||

United States, played in the tragedy. | United States, played in the tragedy. | ||

=CHAPTER = | =CHAPTER = | ||

==1. WHERE AND WHAT KOREA IS ABOVE AND BELOW GROUND== | ==1. WHERE AND WHAT KOREA IS ABOVE AND BELOW GROUND== | ||

NEAR the eastern coast of Asia, at the forty-fourth | |||

parallel of latitude, we find a whorl of mountains | |||

culminating in a peak which Koreans call White | |||

Head Mountain. From this centre mountain ranges | |||

radiate in three directions, one of them going southward and | |||

forming the backbone of the Korean peninsula. The water- | |||

shed is near the eastern coast, and as the range runs southward | |||

it gradually diminishes in height until at last.it is lost in the | |||

sea, and there, with its base in the water, it lifts its myriad | |||

heads to the surface, and confers upon the ruler of Korea the | |||

deserved title of " King of Ten Thousand Islands." A very | |||

large part of the arable land of Korea lies on its western side; | |||

all the long and navigable rivers are there or in the south; | |||

almost all the harbours are on the Yellow Sea. For this reason | |||

we may say that topographically Korea lies with her face toward | |||

China and her back toward Japan. This has had much to do | |||

in determining the history of the country. Through all the | |||

centuries she has set her face toward the west, and never once, | |||

though under the lash of foreign invasion and threatened ex- | |||

tinction, has she ever swerved from her allegiance to her Chinese | |||

ideal. Lacordaire said of Ireland that she has remained " free | |||

by the soul." So it may be said of Korea, that, although forced | |||

into Japan's arms, she has remained " Chinese by the soul." | |||

The climate of Korea may be briefly described as the same | |||

as that of the eastern part of the United States between Maine | |||

and South Carolina, with this one difference, that the prevail- | |||

ing southeast summer wind in Korea brings the moisture from | |||

the warm ocean current that strikes Japan from the south, and | |||

precipitates it over almost the whole of Korea; so that there is | |||

a distinct " rainy season " during most of the months of July | |||

and August. This rainy season also has played an important | |||

part in determining Korean history. Unfortunately for navi- | |||

gation, the western side of the peninsula, where most of the | |||

good harbours are found, is visited by very high tides, and | |||

the rapid currents which sweep among the islands make this | |||

the most dangerous portion of the Yellow Sea. On the eastern | |||

coast a cold current flows down from the north, and makes both | |||

summer and winter cooler than on the western side. | |||

Though the surface of Korea is essentially mountainous, it | |||

resembles Japan very little, for the peninsula lies outside the | |||

line of volcanoes which are so characteristic of the island empire. | |||

Many of the Korean mountains are evidently extinct volcanoes, | |||

especially White Head Mountain, in whose extinct crater now | |||

lies a lake. Nor does Korea suffer at all from earthquakes. | |||

The only remnants of volcanic action that survive are the occa- | |||

sional hot springs. The peninsula is built for the most part | |||

on a granite foundation, and the bare hill-tops, which appear | |||

everywhere, and are such an unwelcome contrast to the foliage- | |||

smothered hills of Japan, are due to the disintegration of the | |||

granite and the erosion of the water during the rainy season. | |||

But there is much besides granite in Korea. There are large | |||

sections where slate prevails, and it is in these sections that the | |||

coal deposits are found, both anthracite and bituminous. It is | |||

affirmed by the Korean people that gold is found in every one | |||

of the three hundred and sixty-five prefectures of the country. | |||

This doubtless is an exaggeration, but it is near enough the | |||

truth to indicate that Korea is essentially a granite formation, | |||

for gold is found, of course, only in connection with such for- | |||

mation. Remarkably beautiful sandstones, marbles and other | |||

building stones are met with among the mountains; and one | |||

town in the south is celebrated for its production of rock crystal, | |||

which is used extensively in making spectacle lenses. | |||

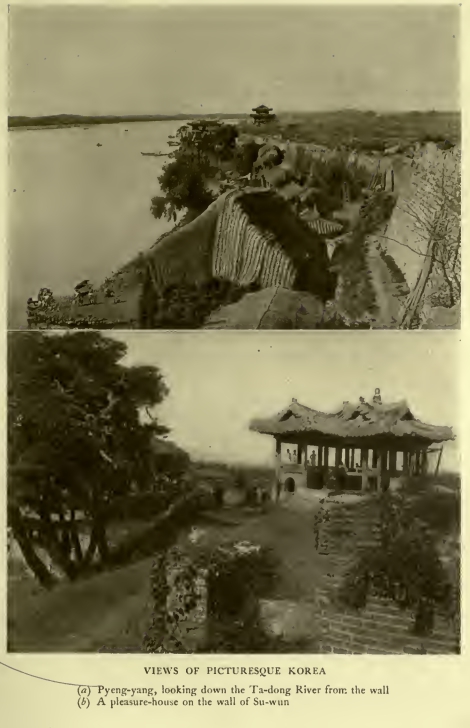

The scenery of Korea as witnessed from the deck of a | |||

steamer is very uninviting, and . it is this which has sent so | |||

many travellers home to assert that this country is a barren, | |||

treeless waste. There is no doubt that the scarcity of timber | |||

along most of the beaten highways of Korea is a certain | |||

blemish, though there are trees in moderate number everywhere ; | |||

but this very absence of extensive forests gives to the scenery | |||

a grandeur and repose which is not to be found in Japanese | |||

scenery. The lofty crags that lift their heads three thousand | |||

feet into the air and almost overhang the city of Seoul are | |||

alpine in their grandeur. There is always distance, openness, | |||

sweep to a Korean view which is quite in contrast to the pic- | |||

turesque coziness of almost all Japanese scenery. This, together | |||

with the crystal atmosphere, make Korea, even after only a few | |||

years' residence, a delightful reminiscence. No people surpass | |||

the Koreans in love for and appreciation of beautiful scenery. | |||

Their literature is full of it. Their nature poems are gems in | |||

their way. Volumes have been written describing the beauties | |||

of special scenes, and Korea possesses a geography, nearly five | |||

hundred years old, in which the beauties of each separate pre- | |||

fecture are described in minute detail, so that it constitutes a | |||

complete historical and scenic guide-book of the entire country. | |||

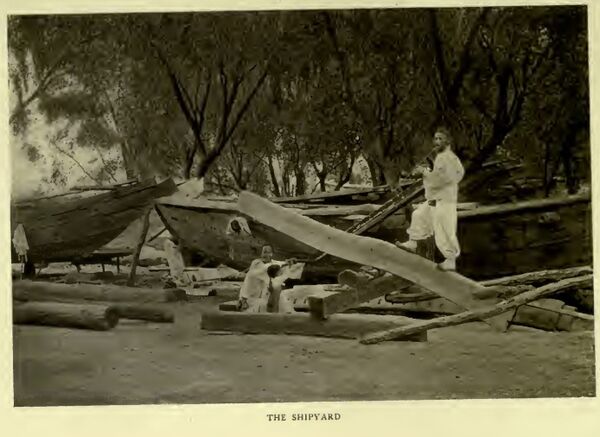

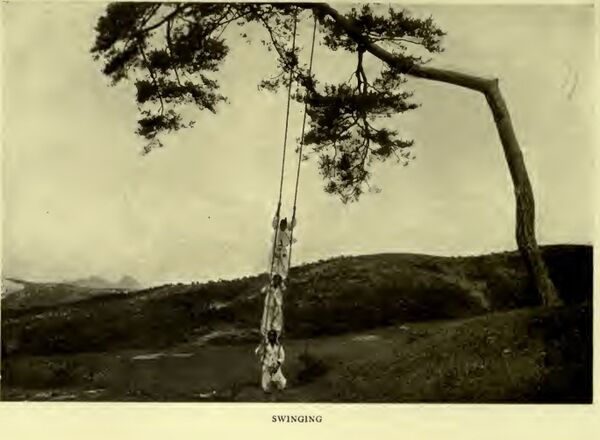

The vegetable life of Korea is like that of other parts of | |||

the temperate zone, but there is a striking preponderance of a | |||

certain kind of pine, the most graceful of its tribe. It forms | |||

a conspicuous element in every scene. The founder of the | |||

dynasty preceding the present one called his capital Song-do, | |||

or Pine Tree Capital. It is a constant theme in Korean art, | |||

and plays an important part in legend and folk-lore in general. | |||

Being an evergreen, it symbolises eternal existence. There are | |||

ten things which Koreans call the chang sang pul sa, or " long- | |||

lived and deathless." They are the pine-tree, tortoise, rock, | |||

stag, cloud, sun, moon, stork, water and a certain moss or | |||

lichen named " the ageless plant." Pine is practically the only | |||

wood used in building either houses, boats, bridges or any other | |||

structure. In poetry and imaginative prose it corresponds to the | |||

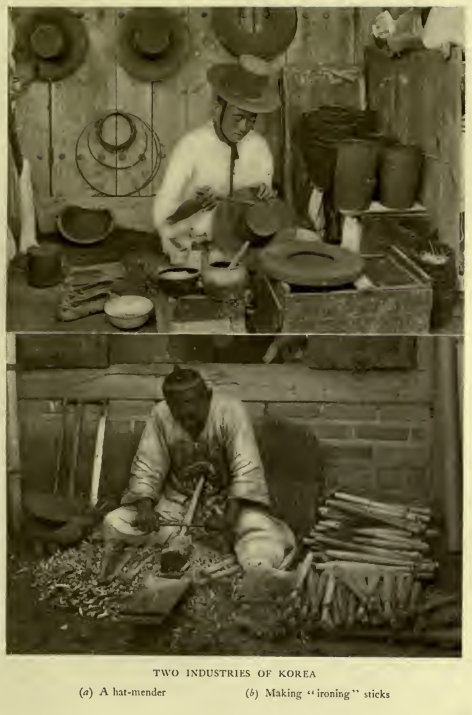

oak of Western literature. Next in importance is the bamboo, | |||

which, though growing only in the southern provinces, is used | |||

throughout the land and in almost every conceivable way. The | |||

domestic life of the Korean would be thrown into dire confu- | |||

sion were the bamboo to disappear. Hats are commonly made | |||

of it, and it enters largely, if not exclusively, into the con- | |||

struction of fans, screens, pens, pipes, tub-hoops, flutes, lanterns, | |||

kites, bows and a hundred other articles of daily use. Take | |||

the bamboo out of Korean pictorial art and half the pictures in | |||

the land would be ruined. From its shape it is the symbol of | |||

grace, and from its straightness and the regular occurrence of | |||

its nodes it is the symbol of faithfulness. The willow is one | |||

of the most conspicuous trees, for it usually grows in the vicinity | |||

of towns, where it has been planted by the hand of man. Thus | |||

it becomes the synonym of peace and contentment. The mighty | |||

row of willows near Pyeng-yang in the north is believed to | |||

have been planted by the great sage and coloniser Kija in | |||

1 122 B. c., his purpose being to influence the semi-savage people | |||

by this object-lesson. From that time to this Pyeng-yang has | |||

been known in song and story as " The Willow Capital." As | |||

the pine is the symbol of manly vigour and strength, so the | |||

willow is the synonym of womanly beauty and grace. Willow | |||

wood, because of its lightness, is used largely in making the | |||

clumsy wooden shoes which are worn exclusively in wet weather ; | |||

and chests are made of it when lightness is desirable. The | |||

willow sprays are used in making baskets of all kinds, so that . | |||

this tree is, in many ways, quite indispensable. Another useful | |||

wood is called the paktal. It has been erroneously called the | |||

sandal-wood, which it resembles in no particular. It is very | |||

like the iron-wood of America, and is used in making the | |||

laundering clubs, tool handles, and other utensils which require | |||

great hardness and durability. It was under a paktal-tree that | |||

the fabled sage Tangun was found seated some twenty-three | |||

hundred years before Christ; so it holds a peculiar place in | |||

Korean esteem. As the pine was the dynastic symbol of Koryu, | |||

918-1392, so the plum-tree is the symbol of this present dynasty. | |||

It was chosen because the Chinese character for plum is the | |||

same as that of the family name of the reigning house. It | |||

was for this cogent reason that the last king of the Koryu | |||

dynasty planted plum-trees on the prophetic site of the present | |||

capital, and then destroyed them all, hoping thereby to blight | |||

the prospects of the Yi family, who, prophecy declared, would | |||

become masters of the land. | |||

There are many hard woods in Korea that are used in the | |||

arts and industries of the people. Oak, ginko, elm, beech and | |||

other species are found in considerable numbers, but the best | |||

cabinet woods are imported from China. An important tree, | |||

found mostly in the southern provinces, is the paper-mulberry, | |||

broussonetai papyrifcra, the inner bark of which is used exclu- | |||

sively in making the tough paper used by Koreans in almost | |||

every branch of life. It is celebrated beyond the borders of the | |||

peninsula, and for centuries formed an important item in the | |||

annual tribute to China and in the official exchange of goods | |||

with Japan. It is intrinsically the same as the superb Japanese | |||

paper, though of late years the Japanese have far surpassed | |||

the Koreans in its manufacture. The cedar is not uncommon | |||

in the country, but its wood is used almost exclusively for | |||

incense in the Buddhist monasteries. Box-wood is used for | |||

making seals and in the finer processes of the xylographic art, | |||

but for this latter purpose pear-wood is most commonly | |||

substituted. | |||

Korea is richly endowed with fruits of almost every kind | |||

common to the temperate zone, with the exception of the apple. | |||

Persimmons take a leading place, for this is the one fruit that | |||

grows to greater perfection in this country than in any other | |||

place. They grow to the size of an ordinary apple, and after | |||

the frost has touched them they are a delicacy that might be | |||

sought for in vain on the tables of royalty in the West. The | |||

apricot, while of good flavour, is smaller than the European | |||

or American product. The peaches are of a deep red colour | |||

throughout and are of good size, but are not of superior quality. | |||

Plums are plentiful and of fair quality. A sort of bush cherry | |||

is one of the commonest of Korean fruits, but it is not grown | |||

by grafting and is inferior in every way. Jujubes, pomegran- | |||

ates, crab-apples, pears and grapes are common, but are gen- | |||

erally insipid to Western taste. Foreign apples, grapes, pears, | |||

peaches, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, currants and | |||

other garden fruits grow to perfection in this soil. As for | |||

nuts, the principal kinds are the so-called English walnuts, | |||

chestnuts and pine nuts. We find also ginko and other nuts, | |||

but they amount to very little. | |||

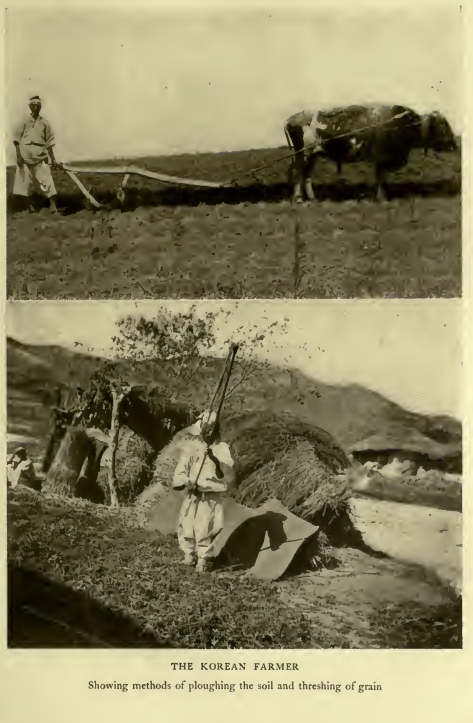

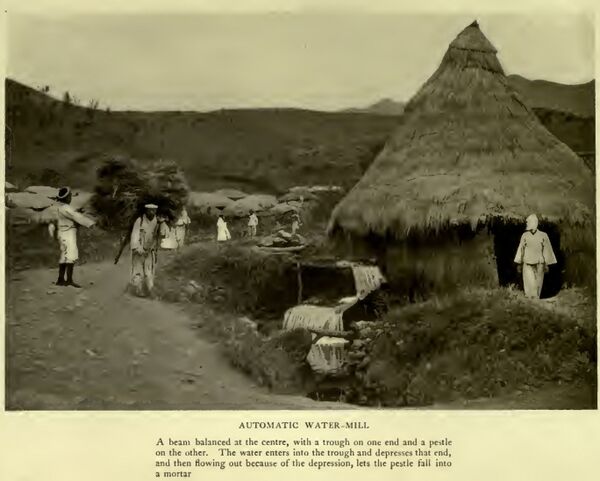

The question of cereals is, of course, of prime importance. | |||

The Korean people passed immediately from a savage con- | |||

dition to the status of an agricultural community without the | |||

intervention of a pastoral age. They have never known any- | |||

thing about the uses of milk or any of its important products, | |||

excepting as medicine. Even the primitive legends do not ante- | |||

date the institution of agriculture in the peninsula. Rice was | |||

first introduced from China in 1122 u. c., but millet had already | |||

been grown here for many centuries. Rice forms the staple | |||

article of food of the vast majority of the Korean people. In | |||

the northern and eastern provinces the proportion of other | |||

grains is more considerable, and in some few places rice is | |||

hardly eaten at all; but the fact remains that, with the excep- | |||

tion of certain mountainous districts where the construction of | |||

paddy-fields is out of the question, rice is the main article of | |||

food of the whole nation. The history of the introduction | |||

and popularisation of this cereal and the stories and poems that | |||

have been written about it would make a respectable volume. | |||

The Korean language has almost as many synonyms for it as | |||

the Arabic has for horse. It means more to him than roast | |||

beef does to an Englishman, macaroni to an Italian, or potatoes | |||

to an Irishman. There are three kinds of rice in Korea. One | |||

is grown in the water, another in ordinary fields, and another | |||

still on the sides of hills. The last is a smaller and harder | |||

variety, and is much used in stocking military granaries, for it | |||

will last eight or ten years without spoiling. The great enemies | |||

of rice are drought, flood, worms, locusts, blight and wind. | |||

The extreme difficulty of keeping paddy-fields in order in such | |||

a hilly country, the absolute necessity of having rains at a par- | |||

ticular time and of not having it at others, the great labour of | |||

transplanting and constant cultivation, — all these things con- | |||

spire to make the production of rice an incubus upon the Korean | |||

people. Ask a Louisiana rice-planter how he would like to | |||

cultivate the cereal in West Virginia, and you will discover | |||

what it means in Korea. But in spite of all the difficulties, | |||

the Korean clings to his favourite dish, and out of a hundred | |||

men who have saved up a little money ninety-nine will buy | |||

rice-fields as being the safest investment. Korean poetry teems | |||

with allusions to this seemingly prosaic cereal. The following | |||

is a free translation of a poem referring to the different species | |||

of rice: | |||

{{인용문|The earth, the fresh warm earth, by heaven's decree, | |||

Was measured out, mile beyond mile afar; | |||

The smiling face which Chosun first upturned | |||

Toward the o'er-arching sky is dimpled still | |||

With that same smile ; and nature's kindly law, | |||

In its unchangeability, rebukes | |||

The fickle fashions of the thing called Man. | |||

The mountain grain retains its ancient shape, | |||

Long-waisted, hard and firm ; the rock-ribbed hills, | |||

On which it grows, both form and fibre yield. | |||

The lowland grain still sucks the fatness up | |||

From the rich fen, and delves for gold wherewith | |||

To deck itself for Autumn's carnival. | |||

Alas for that rude swain who nothing recks | |||

Of nature's law, and casts his seedling grain | |||

Or here or there regardless of its kind. | |||

For him the teeming furrow gapes in vain | |||

And dowers his granaries with emptiness. | |||

To north and south the furrowed mountains stretch, | |||

A wolf gigantic, crouching to his rest. | |||

To east and west the streams, like serpents lithe, | |||

Glide down to seek a home beneath the sea. | |||

The South — warm mother of the race — pours out | |||

Her wealth in billowy floods of grain. The North — | |||

Stern foster-mother — yields her scanty store | |||

By hard compulsion ; makes her children pay | |||

For bread by mintage of their brawn and blood.}} | |||

Millet is the most ancient form of food known in Korea, | |||

and it still forms the staple in most places where rice will not | |||

grow. There are many varieties of millet, all of which flourish | |||

luxuriantly in every province. It is a supplementary crop, in | |||

that it takes the place of rice when there is a shortage in that | |||

cereal owing to drought or other cause. Barley is of great | |||

importance, because it matures the earliest in the season, and so | |||

helps the people tide over a period of scarcity. A dozen vari- | |||

eties of beans are produced, some of which are eaten in con- | |||

nection with rice, and others are fed to the cattle. Beans form | |||

one of the most important exports of the country. Wheat is | |||

produced in considerable quantities in the northern provinces. | |||

Sesamum, sorghum, oats, buckwheat, linseed, corn and a few | |||

other grains are found, but in comparatively small quantities. | |||

As rice is the national dish, we naturally expect to find | |||

various condiments to go with it. Red-peppers are grown | |||

everywhere, and a heavy kind of lettuce is used in making | |||

the favourite sauerkraut, or kimchi, whose proximity is detected | |||

•without the aid of the eye. Turnips are eaten raw or pickled. | |||

A kind of water-cress called minari plays a secondary part | |||

among the- side dishes. In the summer the people revel in | |||

melons and canteloupes, which they eat entire or imperfectly | |||

peeled, and even the presence of cholera hardly calls a halt to | |||

this dangerous indulgence. Potatoes have long been known to | |||

the Koreans, and in a few mountain sections they form the | |||

staple article of diet. They are of good quality, and are largely | |||

eaten by foreign residents in the peninsula. Onions and garlic | |||

abound, and among the well-to-do mushrooms of several vari- | |||

eties are eaten. Dandelions, spinach and a great variety of | |||

salads help the rice to " go down." | |||

Korea is celebrated throughout the East for its medicinal | |||

plants, among which ginseng, of course, takes the leading place. | |||

The Chinese consider the Korean ginseng far superior to any | |||

other. It is of two kinds, — the mountain ginseng, which is so | |||

rare and precious that the finding of a single root once in | |||

three seasons suffices the finder for a livelihood; and the ordi- | |||

nary cultivated variety, which differs little from that found in | |||

the woods in America. The difference is that in Korea it is | |||

carefully cultivated for six or seven years, and then after being | |||

gathered it is put through a steaming process which gives it | |||

a reddish tinge. This makes it more valuable in Chinese esteem, | |||

and it sells readily at high prices. It is a government monopoly, | |||

and nets something like three hundred thousand yen a year. | |||

Liquorice root, castor beans and scores of other plants that | |||

figure in the Western pharmacopoeia are produced, together | |||

with many that the Westerner would eschew. | |||

The Koreans are great lovers of flowers, though compara- | |||

tively few have the means to indulge this taste. In the spring | |||

the hills blush red with rhododendrons and azaleas, and the | |||

ground in many places is covered with a thick mat of violets. | |||

The latter are called the " savage flower," for the lobe is sup- | |||

posed to resemble the Manchu queue, and to the Korean every | |||

Alanchu is a savage. The wayside bushes are festooned with | |||

clematis and honeysuckle, the alternate white and yellow blossoms | |||

of the latter giving it the name " gold and silver flower." The | |||

lily-of-the-valley grows riotously in the mountain dells, and | |||

daffodils and anemones abound. The commonest garden flower | |||

is the purple iris, and many official compounds have ponds | |||

in which the lotus grows. The people admire branches of | |||

peach, plum, apricot or crab-apple as yet leafless but cov- | |||

ered with pink and white flowers. The pomegranate, snow- | |||

ball, rose, hydrangea, chrysanthemum and many varieties of | |||

lily figure largely among the favourites. It is pathetic to | |||

see in the cramped and unutterably filthy quarters of the | |||

very poor an effort being made to keep at least one plant | |||

alive. There is hardly a hut in Seoul where no flower is | |||

found. | |||

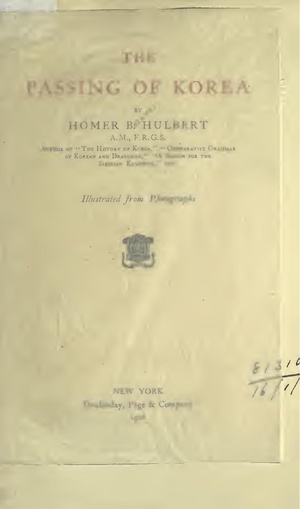

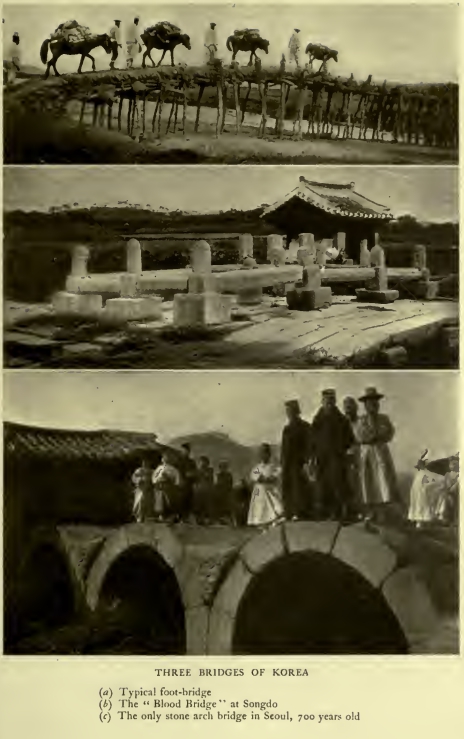

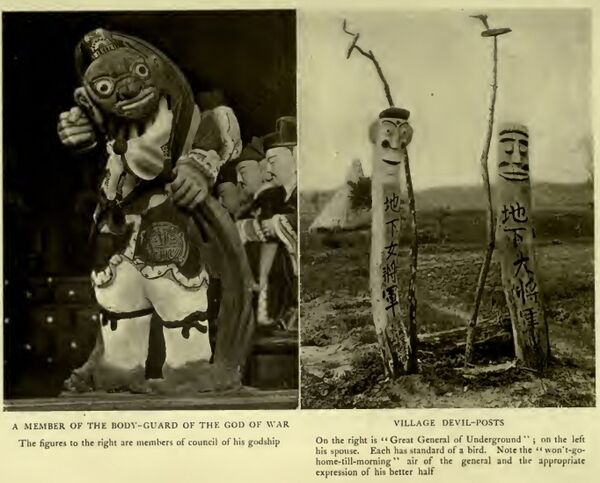

[[파일:01 passing of korea.jpg|600픽셀|섬네일|가운데|The Faithful Fuel-Carriers of Korea]] | |||

As for animal life, Korea has a generous share. The mag- | |||

nificent bullocks which carry the heavy loads, draw the carts and | |||

pull the ploughs are the most conspicuous. It is singular that | |||

the Koreans have never used milk or any of its products, though | |||

the cow has existed in the peninsula for at least thirty-five | |||

hundred years. This is one of the proofs that the Koreans | |||

have never been a nomadic people. Without his bullock the | |||

farmer would be all at sea. No other animal would be able to | |||

drag a plough through the adhesive mud of a paddy-field. Great | |||

mortality among cattle, due to pleuro-pneumonia, not infre- | |||

quently becomes the main cause of a famine. There are no | |||

oxen in Korea. Most of the work is done with bullocks, which | |||

are governed by a ring through the nose and are seldom | |||

obstreperous. Every road in Korea is rendered picturesque by | |||

long lines of bullocks carrying on their backs huge loads of | |||

fuel in the shape of grass, fagots of wood or else fat bags | |||

of rice and barley. As might be expected, cowhides are an | |||

important article of export. | |||

The Korean pony is unique, at least in Eastern Asia. It | |||

is a little larger than the Shetland pony, but is less heavily | |||

built. Two thousand years ago, it is said, men could ride these | |||

animals under the branches of the fruit trees without lowering | |||

the head. They differ widely from the Manchu or Japanese | |||

horse, and appear to be indigenous — unless we may believe the | |||

legend that when the three sages arose from a fissure in the | |||

ground in the island of Quelpart three thousand years ago, | |||

each of them found a chest floating in from the south and | |||

containing a colt, a calf, a pig, a dog and a wife. The pony | |||

is not used in ploughing or drawing a cart, for it is not heavy | |||

enough for such work, but it is used under the pack and under | |||

the saddle, frequently under both, for often the traveller packs | |||

a huge bundle on the pony and then seats himself on top, so | |||

that the animal forms but a vulgar fraction of the whole | |||

ensemble. Foreigners of good stature frequently have to raise | |||

the feet from the stirrup when riding along stony roads. Yet | |||

these insignificant beasts are tough and long-suffering, and will | |||

carry more than half their own weight thirty-five miles a day, | |||

week in and week out. | |||

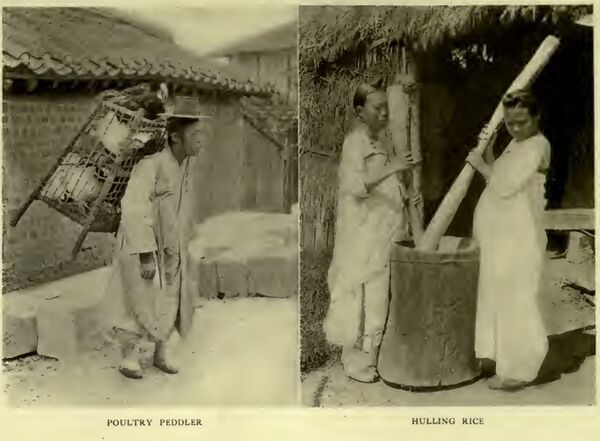

As in all Eastern countries, the pig is a ubiquitous social | |||

factor. We use the word " social " advisedly, for in country vil- | |||

lages at least this animal is always visible, and frequently under | |||

foot. It is a small black breed, and is so poorly fed as to have | |||

practically no lateral development, but resembles the " razor- | |||

backs " of the mountain districts of Tennessee. Its attenuated | |||

shape is typical of the concentrated character of its porcine | |||

obstinacy, as evidenced in the fact that the shrewd Korean | |||

farmer prefers to tie up his pig and carry it to market on | |||

his own back rather than drive it on foot. | |||

Korea produces no sheep. The entire absence of this animal, | |||

except as imported for sacrificial purposes, confirms the suppo- | |||

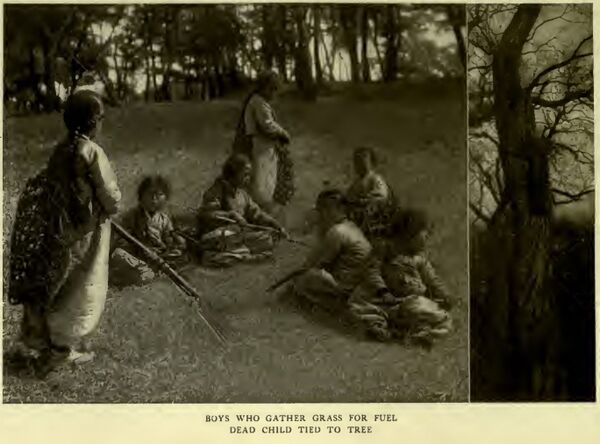

sition that the Koreans have never been a pastoral people. | |||

Foreigners have often wondered why they do not keep sheep | |||

and let them graze on the uncultivable hillsides which form | |||

such a large portion of the area of the country. The answer | |||

is manifold. Tigers, wolves and bears would decimate the | |||

flocks. All arable land is used for growing grain, and what | |||

grass is cut is all consumed as fuel. It would therefore be | |||

impossible to winter the sheep. Furthermore, an expert sheep | |||

man, after examining the grasses common on the Korean hill- | |||

sides, told the writer that sheep could not eat them. The turf | |||

about grave sites and a few other localities would make good | |||

grazing for sheep, but it would be quite insufficient to feed any | |||

considerable number even in summer. | |||

The donkey is a luxury in Korea, being used only by well- | |||

to-do countrymen in travelling. Its bray is out of all propor- | |||

tion to its size, and one really wonders how its frame survives | |||

the wrench of that fearful blast. | |||

Reputable language is hardly adequate to the description of | |||

the Korean dog. No family would be complete without one; | |||

but its bravery varies inversely as the square of its vermin, | |||

which is calculable in no known terms. This dog is a wolfish | |||

breed, but thoroughly domesticated. Almost every house has | |||

a hole in the front door for his accommodation. He will lie | |||

just inside, with his head protruding from the orifice and his | |||

eyes rolling from side to side in the most truculent manner. If | |||

he happens to be outside and you point your finger at him, | |||

he rushes for this hole, and bolts through it at a pace which | |||

seems calculated to tear off all the hair from his prominent | |||

angles. Among certain of the poorer classes the flesh of the | |||

dog is eaten, and we have in mind a certain shop in Seoul | |||

where the purveying of this delicacy is a specialty. We once | |||

shot a dog which entertained peculiar notions about the privacy | |||

of our back yard. The gateman disposed of the remains in a | |||

mysterious manner and then retired on the sick-list for a few | |||

days. When he reappeared at last, with a weak smile on his | |||

face he placed his hand on his stomach and affirmed with evi- | |||

dent conviction that some dogs are too old for any use. But, | |||

on the whole, the Korean dog is cleared of the charge of use- | |||

lessness by the fact that he acts as scavenger in general, and | |||

really does much to keep the city from becoming actually | |||

uninhabitable. | |||

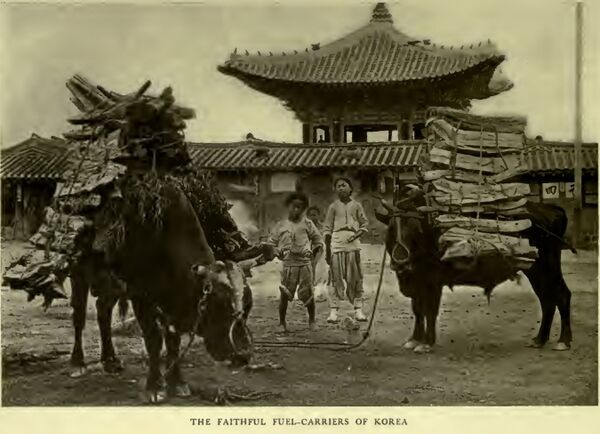

[[파일:02 passing of korea.jpg|600픽셀|섬네일|가운데|Shoeing a Bull]] | |||

The cat is almost exclusively of the back-fence variety, and | |||

is an incorrigible thief. It is the natural prey of the ubiquitous | |||

dog and the small boy. Our observation leads us to the sad | |||

but necessary conclusion that old age stands at the very bottom | |||

of the list of causes of feline mortality. | |||

So much for domestic animals. Of wild beasts the tiger | |||

takes the lead. The general notion that this animal is found | |||

only in tropical or semi-tropical countries is a mistake. The | |||

colder it is and the deeper the snow, the more he will be in evi- | |||

dence in Korea. Country villages frequently have a tiger trap | |||

of logs at each end of the main street, and in the winter time | |||

these are baited with a live animal, — pig for choice. The tiger | |||

attains a good size, and its hair is thick and long. We have seen | |||

skins eleven and a half feet long, with hair two inches and more | |||

in length. This ugly beast will pass through the streets of a | |||

village at night in the dead of winter, and the people are fortu- | |||

nate if he does not break in a door and carry away a child. No | |||

record is kept of the mortality from this cause, but it is probable | |||

that a score or more of people perish annually in this way. | |||

Legend and story are full of the ravages of the tiger. He is | |||

supposed to be able to imitate the human voice, and thus lure | |||

people out of their houses at night. Koreans account for the | |||

fierceness of his nature by saying that in the very beginning of | |||

things the Divine Being offered a bear and a tiger the opportunity | |||

of becoming men if they would endure certain tests. The bear | |||

passed the examination with flying colours, but the tiger suc- | |||

cumbed to the trial of patience, and so went forth the greatest | |||

enemy of man. | |||

Deer are common throughout the land, and at the proper | |||

season they are eagerly sought for because of their soft horns, | |||

which are considered of great medicinal value. Wealthy Koreans | |||

who are ailing often go among the mountains with the hope of | |||

being in at the death of a young buck, and securing a long | |||

draught of the warm blood, which they look upon as nearly | |||

equivalent to the fountain of eternal youth. The exercise required | |||

for this is in itself enough to make an ill man well, so the fiction | |||

about the blood is not only innocent but valuable. | |||

The bear is found occasionally, but is of a small breed and | |||

does comparatively little damage. The wild boar is a formidable | |||

animal, and is considered fully as dangerous to meet as the tiger, | |||

because it will charge a supposed enemy at sight. We have seen | |||

specimens weighing well toward four hundred pounds and with | |||

formidable tushes. The fox is found in every town and district | |||

in the country. It is the most detested of all things. It is the | |||

epitome of treachery, meanness and sin. The land is full of | |||

stories of evil people who turned out to be foxes in the disguise | |||

of human form. And of all foxes the white one is the worst, | |||

but it is doubtful whether such has ever been seen in Korea. Tra- | |||

dition has no more opprobrious epithet than " fox." Even the | |||

tiger is less dangerous, because less crafty. The wolf is com- | |||

paratively little known, but occasionally news comes from some | |||

distant town that a child has been snatched away by a wolf. | |||

The leopard is another supposedly tropical animal that flour- | |||

ishes in this country. Its skin is more largely used than that | |||

of the tiger, but only officials of high rank are allowed the | |||

luxury. | |||

Among lesser animals are found the badger, hedgehog, | |||

squirrel, wildcat, otter, weasel and sable. The last is highly | |||

prized for its skin, but it is of poorer quality than that of the | |||

Siberian sable. At the same time many handsome specimens | |||

have been picked up here. The Koreans value most highly the | |||

small spot of yellow or saffron that is found under the throat | |||

of the sable. We have seen whole garments made of an almost | |||

countless number of such pieces. Naturally it takes a small for- | |||

tune to acquire one of them. | |||

For its bird life, especially game birds, Korea is deservedly | |||

famous. First comes the huge bustard, which stands about four | |||

feet high and weighs, when dressed, from twenty to thirty | |||

pounds. It is much like the wild turkey, but is larger and gamier. | |||

The beautiful Mongolian pheasant is found everywhere in the | |||

country, and in winter it is so common in the market that it | |||

brings only half the price of a hen. Within an hour of Seoul | |||

one can find excellent pheasant shooting at the proper season. | |||

Ducks of a dozen varieties, geese, swan and other aquatic birds | |||

abound in such numbers that one feels as if he were taxing the | |||

credulity of the reader in describing them. In the winter of 1891 | |||

the ducks migrated apparently in one immense flock. Their | |||

approach sounded like the coming of a cyclone, and as they | |||

passed, the sky was completely shut out from view. It would | |||

have been impossible to get a rifle bullet between them. They | |||

do not often migrate this way, but flocks of them can be seen in | |||

all directions at almost any time of day during the season. Even | |||

as we write, information comes that a party of three men | |||

returned from two days' shooting with five hundred and sixty | |||

pounds of birds. Quail, snipe and other small birds are found | |||

in large quantities, but the hunter scorns them in view of the | |||

larger game. Various kinds of storks, cranes and herons find | |||

abundance of food in the flooded paddy-fields, where no one | |||

thinks of disturbing them. One of the sights of Seoul is its airy | |||

scavengers, the hawks, who may be seen sometimes by the score | |||

sailing about over the town. Now and again one of them will | |||

sweep down and seize a piece of meat from a bowl that a woman | |||

is carrying home on her head. It is not uncommon to see small | |||

boys throwing dead mice into the air to see the hawks swoop | |||

down and seize them before they reach the ground. | |||

Korea contains plenty of snakes, but none of them are spe- | |||

cially venomous, although there are some whose bite will cause | |||

considerable irritation. Many snakes live among the tiles of | |||

the roofs, where they subsist on the sparrows that make their | |||

nests under the eaves. These snakes are harmless fellows, and | |||

when you see one hanging down over your front door in the | |||

dusk of evening it should cause no alarm. The people say, and | |||

believe it too, that if a snake lives a thousand years it assumes | |||

a short and thick shape and acquires wings, with which it flies | |||

about with inconceivable rapidity, and is deadly not only because | |||

of its bite, but if a person even feels the wind caused by its light- | |||

ning flash as it speeds by he will instantly die. Formerly, | |||

according to Korean tradition, there were no snakes in Korea; | |||

but when the wicked ruler Prince Yunsan (1495-1506) had | |||

worn himself out with a life of excesses, he desired to try the | |||

effect of keeping a nest of snakes under his bed, for he had heard | |||

that this would restore lost vitality. So he sent a boat to India, | |||

and secured a cargo of selected ophidians, and had them brought | |||

to Korea. The cargo was unloaded at Asan; but it appears | |||

that the stevedores had not been accustomed to handle this kind | |||

of freight, and so a part of the reptiles made their escape into | |||

the woods. From that time; so goes the tale, snakes have existed | |||

here as elsewhere. Unfortunately no one has ever made a study | |||

of serpent worship in Korea, but there appears to be some reason | |||

to believe that there was once such a cult. The Koreans still | |||

speak of the op-kuregi, or " Good Fortune Serpent " ; and as | |||

most of the natives have little other religion than that of praying | |||

to all kinds of spirits for good luck, it can hardly be doubted that | |||

the worship of the serpent in some form has existed in Korea. | |||

Though there are no deadly snakes in the country, there are | |||

insects that annually cause considerable loss of life. The centi- | |||

pede attains a growth of six or seven inches, and a bite from one | |||

of them may prove fatal, if not attended to at once. The Koreans | |||

cut up centipedes and make a deadly drink, which they use, as | |||

hemlock was used in Greece, for executing criminals. This has | |||

now gone out of practice, however, thanks to the enlightening | |||

contact with Westerners, who simply choke a man to death with | |||

a rope ! Among the mountains it is said that a poisonous spider | |||

is found ; but until this is verified we dare not vouch for it. | |||

The tortoise plays an important part in Korean legend and | |||

story. He represents to the Korean mind the principle of healthy | |||

conservatism. He is never in a hurry, and perhaps this is why | |||

the Koreans look upon him with such respect, if not affection. | |||

All animals in Korea are classed as good or bad. We have | |||

already said that the fox is the worst. The tiger, boar, frog and | |||

mouse follow. These are all bad ; but the bear, deer, tortoise, | |||

cow and rabbit are all good animals. | |||

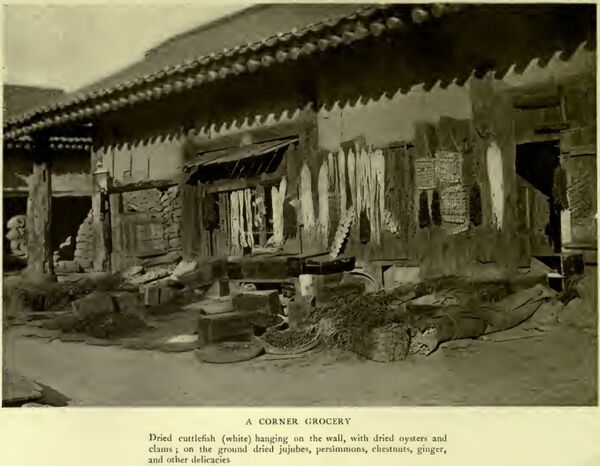

More important than all these, except cattle, are the fish of | |||

Korea. The waters about the peninsula swarm with fish of a | |||

hundred kinds. They are all eaten by the people, even the sharks | |||

and the octopi. The commonest is the ling, which is caught in | |||

enormous numbers off the east coast, and sent all over the country | |||

in the dried form. Various kinds of clams, oysters and shrimps | |||

are common. Whales are so numerous off the eastern coast that | |||

a flourishing Japanese company has been employed in catching | |||

them of late years. Pearl oysters are found in large numbers | |||

along the southern coast, and the pearls would be of considerable | |||

value if the Koreans knew how to abstract them from the shells | |||

in a proper manner. | |||

But fish and pearls are not the only sea-products that the | |||

Korean utilises. Enormous quantities of edible seaweed are | |||

gathered, and the sea-slug, or beche-de-mer, is a particular deli- | |||

cacy. The Koreans make no use of those bizarre dishes for | |||

which the Chinese are so noted, such as birds' nests and the like. | |||

Their only prandial eccentricity is boiled dog, and that is strictly | |||

confined to the lowest classes. | |||

==2. THE PEOPLE== | ==2. THE PEOPLE== | ||

= | study of the origin and the ethnological affinities | ||

of the Korean people is yet in its infancy. Not until | |||

a close and exhaustive investigation has been made | |||

of the monuments, the folk-lore, the language and | |||

all the other sources of information can anything be said defi- | |||

nitely upon this question. It will be in place, therefore, to | |||

give here the tentative results already arrived at, but without | |||

dogmatising. | |||

Oppert was the first to note that in Korea there are two types | |||

of face, — the one distinctly Mongolian, and the other lacking | |||

many of the Mongolian features and tending rather to the Malay | |||

type. To the new-comer all Koreans look alike; but long resi- | |||

dence among them brings out the individual peculiarities, and | |||

one comes to recognise that there are as many kinds of face here | |||

as in the West. Dr. Baelz, one of the closest students of Far | |||

Eastern physiognomy, recognises the dual nature of the Korean | |||

type, and finds in it a remarkable resemblance to a similar feature | |||

of the Japanese, among whom we learn that there is a certain | |||

class, probably descendants of the ancient Yamato race, which | |||

has preserved to a great extent the same non-Mongolian cast of | |||

features. This seems to have been overlaid at some later time | |||

by a Polynesian stock. The ethnological relation between the | |||

non-Mongolian type in Korea and the similar type in Japan is | |||

one of the most interesting racial problems of the Far East. | |||

I feel sure that it is the infusion of this type into Korea and Japan | |||

that has differentiated these peoples so thoroughly from the | |||

Chinese. | |||

Five centuries before Christ, northern Korea and southern | |||

Korea were very clearly separated. The Kija dynasty in the | |||

north had consolidated the people into a more or less homo- | |||

geneous state, but this kingdom never extended south further | |||

than the Han River. At this time the southern coast of the | |||

peninsula was peopled by a race differing in essential particulars | |||

from those of the north. Their language, social system, govern- | |||

ment, customs, money, ornaments, traditions and religion were | |||

all quite distinct from those of the north. Everything points | |||

to the belief that they were maritime settlers or colonists, and | |||

that they had come to the shores of Korea from the south. | |||

The French missionaries in Korea were the first to note a | |||

curious similarity between the Korean language and the lan- | |||

guages of the Dravidian peoples of southern India. It is well | |||

established that India was formerly inhabited by a race closely | |||

allied to the Turanian peoples, and that when the Aryan con- | |||

querors swept over India the earlier tribes were either driven in | |||

flight across into Burmah and the Malay Peninsula, or were | |||

forced to find safety among the mountains in the Deccan. From | |||

the Malay Peninsula we may imagine them spreading in various | |||

directions. Some went north along the coast, others into the | |||

Philippine Islands, then to Formosa, where Mr. Davidson, the | |||

best authority, declares tHat the Malay type prevails. The power- | |||

ful " Black Current," the Gulf Stream of the Pacific, naturally | |||

swept northward those who were shipwrecked. The Liu-Kiu | |||

Islands were occupied, and the last wave of this great dispersion | |||

broke on the southern shores of Japan and Korea, leaving there | |||

the nucleus of those peoples who resemble each other so that if | |||

dressed alike they cannot be distinguished as Japanese or Korean | |||

even by an expert. The small amount of work that has been | |||

so far done indicates a striking resemblance between these south- | |||

ern Koreans and the natives of Formosa, and the careful com- | |||

parison of the Korean language with that of the Dravidian | |||

peoples of southern India reveals such a remarkable similarity, | |||

phonetic, etymologic, and syntactic, that one is forced to recognise | |||

in it something more than mere coincidence. The endings of | |||

many of the names of the ancient colonies in southern Korea are | |||

the exact counterpart of Dravidian words meaning " settlement " | |||

or " town." The endings -caster and -coin in English are no | |||

more evidently from the Latin than these endings in Korea are | |||

from the Dravidian. | |||

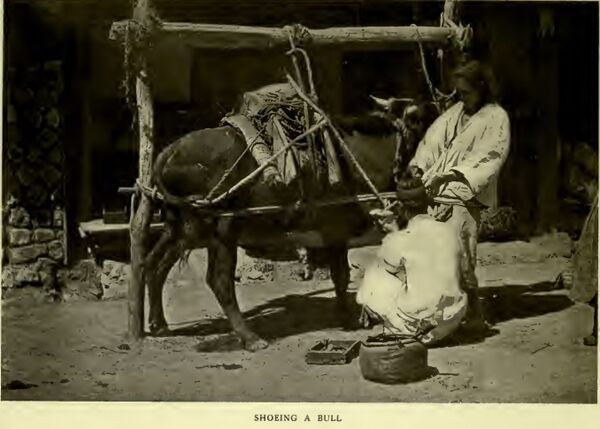

[[파일:03 passing of korea.jpg|600픽셀|섬네일|가운데|American Bridgo Across the Han - Looking north toward Seoul]] | |||

The early southern Koreans were wont to tattoo their bodies. | |||

The custom has died out, since the more rigorous climate of the | |||

peninsula compels the use of clothing covering the whole body. | |||

The description of the physiological features of those Dravidian | |||

tribes which have suffered the least from intermixture with others | |||

coincides in every particular with the features of the Korean. | |||

Of course it is impossible to go into the argument in cxtenso | |||

here; but the most reasonable conclusion to be arrived at to-day | |||

is that the peninsula of Korea is inhabited by two branches | |||

of the same original family, a part of which came around | |||

China by way of the north, and the other part by way of the | |||

south. | |||

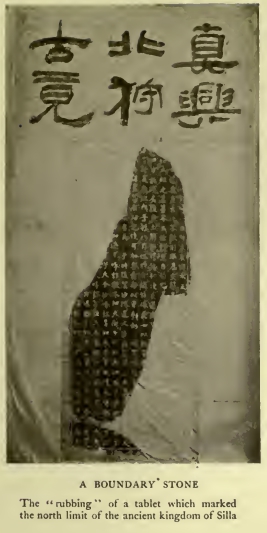

As we see in the historical review given elsewhere in these | |||

pages, the southern kingdom of Silla was the first to obtain | |||

control of the entire peninsula and impose her laws and language, | |||

and it is for this reason that the language to-day reflects much | |||

more of the southern stock than of the northern.<ref>A full description of the linguistic affinities of Korean to the Dravidian dia- | |||

lects will be found in the author's Comparative Grammar of Korean and Dravidian. </ref> | |||

=== CHARACTERISTICS === | |||

In discussing the temperament and the mental characteristics | |||

of the Korean people, it will be necessary to begin with the trite | |||

saying that human nature is the same the world over. The new- | |||

comer to a strange country like this, where he sees so many | |||

curious and, to him, outlandish things, feels that the people are | |||

in some way essentially different from himself, that they suffer | |||

from some radical lack; but if he were to stay long enough to | |||

learn the language, and get behind the mask which hides the | |||

genuine Korean from his mental view, he would find that the | |||

Korean might say after old Shylock, " I am a Korean. Hath | |||

not a Korean eyes? Hath not a Korean hands, organs, dimen- | |||

sions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt | |||

with the same weapons? subject to the same diseases? healed | |||

with the same means ? warmed and cooled by the same summer | |||

and winter as the Westerner is ? If you prick us, do we not bleed ? | |||

If you tickle us, do we not laugh ? If you poison us, do we not | |||

die? And if you wrong us, shall we not be revenged? " In other | |||

words, he will find that the differences between the Oriental and | |||

the Occidental are wholly superficial, the outcome of training and | |||

environment, and not of radical dissimilarity of temperament. | |||

But there is this to be said: it is far easier to get close to a | |||

Korean and to arrive at his point of view than to get close to | |||

a Japanese or a Chinese. Somehow or other there seems to be | |||

a greater temperamental difference between the Japanese or | |||

Chinese and the Westerner than between the Korean and the | |||

Westerner. I believe the reason for this lies in the fact of the | |||

different balance of temperamental qualities in these different | |||

peoples. The Japanese are a people of sanguine temperament. | |||

They are quick, versatile, idealistic, and their temperamental | |||

sprightliness approaches the verge of volatility. This quality | |||

stood them in good stead when the opportunity came for them | |||

to make the great volte face in 1868. It was a happy leap in | |||

the dark. In the very same way the Japanese often embarks upon | |||

business enterprises, utterly sanguine of success, but without | |||

forecasting what he will do in case of disaster. The Chinese, | |||

on the other hand, while very superstitious, is comparatively | |||

phlegmatic. He sees no rainbows and pursues no ignes fatui. | |||

He has none of the martial spirit which impels the Japanese to | |||

deeds of patriotic daring. But he is the best business man in the | |||

world. He is careful, patient, persevering, and content with | |||

small but steady gains. No one knows better than he the ultimate | |||

evil results of breaking a contract. Without laying too much | |||

emphasis upon these opposite tendencies in the Japanese and | |||

Chinese, we may say that the former lean toward the idealistic, | |||

while the latter lean toward the utilitarian. The temperament | |||

of the Korean lies midway between the two, even as his country | |||

lies between Japan and China. This combination of qualities | |||

makes the Korean rationally idealistic. Those who have seen | |||

the Korean only superficially, and who mark his unthrifty habits, | |||

his happy-go-lucky methods, his narrowness of mind, will think | |||

my characterisation of him flattering ; but those who have gone | |||

to the bottom of the Korean character, and are able to distin- | |||

guish the true Korean from some of the caricatures which have | |||

been drawn of him, will agree that there is in him a most happy | |||

combination of rationality and emotionalism. And more than | |||

this, I would submit that it is the same combination that has | |||

made the Anglo-Saxon what he is. He is at once cool-headed | |||

and hot-headed. He can reason calmly and act at white heat. | |||

It is this welding of two different but not contrary characteris- | |||

tics that makes the power of the Anglo-Saxon peoples. It will | |||

be necessary to show, therefore, why it is that Korea has done | |||

so little to justify the right to claim such exceptional qualities. | |||

But before doing this, I would adduce a few facts to show on | |||

what my claim is based. | |||

In the first place, it is the experience of those who have had | |||

to do with the various peoples of the Far East that it is easier | |||

to understand the Korean and get close to him than it is to | |||

understand either the Japanese or the Chinese. He is much more | |||

like ourselves. You lose the sense of difference very readily, and | |||

forget that he is a Korean and not a member of your own race. | |||

This in itself is a strong argument; for it would not be so if | |||

there were not some close intellectual, or moral, or tempera- | |||

mental bond of sympathy. The second argument is a religious | |||

one. The religions of China were forced upon Korea irrespective | |||

of her needs or desires. Confucianism, while apparently satis- | |||

factory to a man utterly devoid of imagination (a necessary | |||

instrument to be used in the work of unifying great masses of | |||

population, by anchoring them to the dead bones of their ances- | |||

tors), can be nothing less than contemptible to a man possessed | |||

of actual humour. Two things have preserved the uniform politi- | |||

cal solidarity of the Chinese Empire for the last three thousand | |||

years, — the sacred ideograph and the ancestral grave. But | |||

Confucianism is no religion ; it is simply patriarchal law. That | |||

law, like all other civil codes, received its birth and nutriment | |||

from the body politic of China by natural generation. But the | |||

Korean belongs to a different intellectual and temperamental | |||

species, and thus the law which was bone of China's bone and | |||

flesh of her flesh was less than a foster-child to Korea. Its | |||

entire lack of the mystical element renders it quite incapable of | |||

satisfying the religious cravings of such a people as the Koreans. | |||

Buddhism stands at the opposite pole from Confucianism. It is | |||

the most mystical of all cults outside the religion of the Nazarene. | |||

This is why it has become so strongly intrenched in Japan. While | |||

Confucianism leaves nothing to the imagination, Buddhism | |||

leaves everything. The idealism of the, Japanese surrendered to | |||

it, and we may well believe that when Buddhism is driven to bay | |||

it will not be at Lhasa, the home of the Lamas, but at Nara or | |||

at Nikko. Here again that rational side of the Korean tempera- | |||

ment came in play. While Confucianism contained too little | |||

mysticism for him, Buddhism contained too much ; and so, while | |||

nominally accepting both, he made neither of them a part of | |||

himself. | |||

It is said that when a company of Tartar horsemen capture | |||

one of the enemy they bury him to the neck in the earth, pack the | |||

dirt firmly about him so that he can move neither hand nor foot, | |||

place a bowl of water and a bowl of food just before his face, | |||

and leave him to die of hunger, thirst or sunstroke, or to be | |||

torn by wolves. This is the way, metaphorically, in which Korea | |||

was treated to religions. Both kinds were placed before her very | |||

face, but she could partake of neither. The sequel is important. | |||

The Christian religion was introduced into Korea by the Roman | |||

Catholics about a century ago, and by Protestants two decades | |||

ago. The former made considerable advance in spite of terrible | |||

persecution, but their rate of advance was slow compared with | |||

what has been done by the Protestant missionaries. I make bold | |||

to say that the Christian religion, shorn of all trappings and | |||

embellishments of man's making, appeals perfectly to the ration- | |||

ally emotional temperament of the Korean. And it is to some | |||

extent this perfect adaptability which has won for Christianity | |||

such a speedy and enthusiastic hearing in this country. Chris- | |||

tianity is at once the most rational and the most mystical of reli- | |||

gions, and as such is best fitted, humanly speaking, to appeal to | |||

this people. This, of course, without derogation from its uni- | |||

versal claims. One has but to consult the records of modern | |||

missions to see what a wonderful work has been done in this | |||

land by men who are presumably no more and no less devoted | |||

than those at work in other fields. | |||

Being possessed, then, of a temperament closely allied to that | |||

of the Anglo-Saxon, what has caused the present state of intel- | |||

lectual and moral stagnation? Why is it that most people look | |||

upon the Korean as little better than contemptible? It is because | |||

in the sixth and seventh centuries, when Korea was in her forma- | |||

tive stage, when she was just ready to enter upon a career of inde- | |||

pendent thought and achievement, the ponderous load of Chinese | |||

civilisation was laid upon her like an incubus. She knew no | |||

better than to accept these Chinese ideals, deeming in her igno- | |||

rance that this would be better than to evolve ideals of her own. | |||

From that time to this she has been the slave of Chinese thought. | |||

She lost all spontaneity and originality. To imitate became her | |||

highest ambition, and she lost sight of all beyond this contracted | |||

horizon. Intrinsically and potentially the Korean is a man of | |||

high intellectual possibilities, but he is, superficially, what he is | |||

by virtue of his training and education. Take him out of this | |||

environment, and give him a chance to develop independently | |||

and naturally, and you would have as good a brain as the Far | |||

East has to offer. | |||

Korea is a good illustration of the great influence which | |||

environment exerts upon a people's mental and moral character- | |||

istics. I am not sure that the conservatism of either the Korean | |||

or the Chinese is a natural characteristic. The population of | |||

China is so vast and so crowded, social usages have become so | |||

stereotyped, the struggle for bare existence is so keen, that the | |||

slightest disturbance in the running of the social machine is sure | |||

to plunge thousands into immediate destitution and despair. At | |||

this point lies the enormous difficulty of reforming that country. | |||

It is like a huge machine, indescribably complicated, and so deli- | |||

cately adjusted that the variation of a hair's-breadth in any part | |||

will bring the whole thing to a standstill. Let me illustrate. | |||

There are a great many foreigners in China who are trying to | |||

evolve a phonetic system of writing for that country. It is | |||

a most laudable undertaking; but the system which has received | |||

most approbation is one in which our Roman letters are used | |||

to indicate the various sounds of that language. But these letters | |||

are made by the use of straight and curved lines, the latter being | |||

almost exclusively used in ordinary writing. Now we know | |||

that over two thousand years ago the Chinese discarded a system | |||

based upon curved lines, because it was found impossible to make | |||

them readily with the brush pen, universally used throughout | |||

the Far East. The introduction of a system containing a large | |||

proportion of curved lines implies, therefore, that the brush pen | |||

will be laid aside in favour of a hard pen, either in the form of | |||

our Western pen or in some similar form. Note the result. The | |||

use of a metal pen and fluid ink will do away with the brush pen, | |||

and will affect the industry whereby a million people make an | |||

already precarious living. The manufacture of india ink will | |||

likewise go to the wall. The paper now used in all forms of | |||

writing will be useless, and a very few, if any, of the manufac- | |||

turing plants now in operation can be utilised for the manu- | |||

facture of the hard, calendered paper which is needed for use | |||

with the steel pen. Moreover, the ink-stones, water-cups, writing- | |||

tablets, and all the other paraphernalia in use at the present time | |||

will have to be thrown away, and all the people engaged in the | |||

manufacture of these things will be deprived of their means of | |||

support. All this is likely to happen if the system proposed is | |||

to become the general rule. Note how far-reaching even such | |||

a seemingly small change as this will be. It might be possible | |||

if there were any margin upon which all these people could sub- | |||

sist during the process of change; but there is none. It is for | |||

this reason that the present writer has urged that the Chinese | |||

people be invited to adopt the Korean alphabet, which is as simple | |||

in structure as any, and capable of the widest phonetic adapta- | |||

tion. It is a " square " character, and could therefore be written | |||

with the brush pen, as it is to-day by the Korean. The same | |||

paper, ink, and other apparatus now in use in China could be | |||

retained, and the only work to be done in introducing it is to | |||

overcome the sentimental prejudice of the Chinese in favour of | |||

the ideograph. It would affect the daily occupation of almost | |||

no Chinese workmen at all. This illustration has gone too far; | |||

but it will help to show how firmly these customs have sunk their | |||

roots in the soil of these nations, and it shows that conservatism | |||

has become a necessity of life, however much one might wish to | |||

get rid of it. But let us get back to Korea. | |||

The Korean is highly conservative. One of his proverbs is | |||

that " If you try to shorten the road by going across lots, you | |||

will fall in with highwaymen." This is a strong plea for stay- | |||

ing in the old ruts. His face is always turned back toward | |||

the past. He sees no statesmen, warriors, scholars or artists | |||

to-day that are in any way comparable with those of the olden | |||

times; nor does he even believe that the present is capable of | |||

evolving men who are up to the standard of those of former | |||

times. | |||

But in spite of all this, he can be moved out of his conservatism | |||

by an appeal to his self-interest. The introduction of friction | |||

matches will illustrate this point. The Korean was confined to | |||

the use of flint and steel until about thirty years ago ; but when | |||

matches entered the country in the wake of foreign treaties, he | |||

saw almost at once that they were cheaper and better in every | |||

way than his old method, and he adopted them without the least | |||

remonstrance. There were a few fossils who clung to the flint | |||

and steel out of pure hatred of the new article, but they were | |||

laughed at by the overwhelming majority. The same is true of | |||

the introduction of petroleum, sewing-needles, thread, soap and | |||

a thousand other articles of daily use. The same is true in | |||

China. There is no conservatism that will stand out against | |||

self-interest. | |||

And here we touch a second characteristic of the Korean. | |||

It cannot be truthfully said that the Korean is niggardly. It has | |||

been the opinion of most who have had intimate dealings with | |||

him that he is comparatively generous. He is generally lavish | |||

with his money when he has any, and when he has none he is | |||

quite willing to be lavish with some one else's money. Most | |||

foreigners have had a wider acquaintance with the latter than | |||

with the former. He is no miser. He considers that money is | |||

made to circulate, and he does his best to keep it from stagna- | |||

tion. He thinks that it is not worth getting unless it can be | |||

gotten easily. I doubt whether there is any land where the | |||

average citizen has seen greater ups and downs of pecuniary | |||

fortune. Having a handsome competence, he invests it all in | |||

some wild venture at the advice of a friend, and loses it all. He | |||

grumbles a little, but laughs it off, and saunters along the street | |||

with as much unconcern as before. It went easily — he will get | |||

some more as easily. And, to tell the truth, he generally does. | |||

It is simply because there are plenty more as careless as himself. | |||

He is undeniably improvident; but there is in it all a dash of | |||

generosity and a certain scorn of money which make us admire | |||

him for it, after all. I have seen Koreans despoiled of their | |||

wealth by hideous official indirection which, in the Anglo-Saxon, | |||

would call for mob law instantly ; but they carried it off with a | |||

shrug of the shoulders and an insouciance of manner which | |||

would have done credit to the most hardened denizen of Wall | |||

Street. I am speaking here of the average Korean, but there are | |||

wide variations in both directions. There are those who hoard | |||

and scrimp and whine for more, and there are those who are | |||

not only generous but prodigal. Foreigners are unfavourably | |||

impressed by the willingness with which the Korean when in | |||

poor circumstances will live on his friends ; but this is to a large | |||

extent offset by the willingness with which he lets others live | |||

on him when he is in flourishing circumstances. Bare chance | |||

plays such a prominent part in the acquisition of a fortune here, | |||

that the favoured one is quite willing to pay handsomely for his | |||

good luck. And yet the Korean people are not without thrift. | |||

If a man has money, he will generally look about for a safe place | |||

to invest it. It is because the very safest places are still so unsafe | |||

that fortune has so much to do with the matter. He risks his | |||

money with his eyes wide open. He stands to win largely or | |||

lose all. An investment that does not bring in forty per cent a | |||

year is hardly satisfactory, nor should it be satisfactory, since | |||

the chances of loss are so great that the average of gain among | |||

a score of men will probably be no more than in our own lands. | |||

Why the chances of loss are so great will be discussed in its | |||

proper place. | |||

Another striking characteristic of the Korean is his hospi- | |||

tality. This is a natural sequence of his general open-handedness. | |||

The guest is treated with cordial courtesy, whatever differences | |||

of opinion there may be or may have been between them. For | |||

the time being he is a guest, and nothing more. If he happens | |||

to be present at the time for the morning or afternoon meal, it is | |||

de rigeur to ask him to have a table of food ; and many a man | |||

is impoverished by the heavy demands which are made upon | |||

his hospitality. Not that others have knowingly taken undue | |||

advantage of his good nature, but because his position or his | |||

business and social connections have made it necessary to keep | |||

open house, as it were. A Korean gentleman of my acquaint- | |||

ance, who can live well on twenty dollars a month in the country, | |||

recently refused a salary of twice that sum in Seoul on the plea | |||

that he had so many friends that he could not live on that amount. | |||

Seoul is very ill-supplied with inns ; in fact, it has very little use | |||

for them. Everyone that comes up from the country has a | |||

friend with whom he will lodge. It must be confessed that there | |||

are a considerable number of young men who come up to Seoul | |||

and stay a few days with each of their acquaintances in succes- | |||

sion ; and if they have a long enough calling list, they can man- | |||

age to stay two or three years in the capital free of board and | |||

lodgings. Such a man finally becomes a public nuisance, and | |||

his friends reluctantly snub him. He always takes this hint | |||

and retires to his country home. I say that they reluctantly snub | |||

him, for the Korean is mortally afraid of being called stingy. | |||

You may call him a liar or a libertine, and he will laugh it off; | |||

but call him mean, and you flick him on the raw. Hospitality | |||

toward relatives is specially obligatory, and the abuse of it forms | |||

one of the most distressing things about Korea. The moment | |||

a man obtains distinction and wealth he becomes, as it were, the | |||

social head of his clan, and his relatives feel at liberty to visit | |||

him in shoals and stay indefinitely. They form a sort of social | |||

body-guard, — a background against which his distinction can | |||

be well displayed. If he walks out, they are at his elbow to | |||

help him across the ditches; if he has any financial transactions | |||

to arrange, they take the onerous duty off his hands. Meanwhile | |||

every hand is in his rice-bag, and every dollar spent pays toll to | |||

their hungry purses. It amounts to a sort of feudal communism, | |||

in which every successful man has to divide the profits with his | |||

relatives. | |||

Another marked characteristic of the Korean is his pride. | |||

There are no people who will make more desperate attempts to | |||

keep up appearances. Take the case of one of our own nouveaux | |||

riches trying in every way to insinuate himself into good society, | |||

and you will have a good picture of a countless multitude of | |||

Koreans. In spite of the lamentable lack of effort to better their | |||

intellectual status or to broaden their mental horizon, there is | |||

a passionate desire to ascend a step on the social ladder. Put the | |||

average Korean in charge of a few dollars, even though they be | |||

not his own, or give him the supervision of the labour of a few | |||

men, — anything that will put him over somebody either physi- | |||

cally or financially, and he will swell almost to bursting. Any | |||

accession of importance or prestige goes to his head like new | |||

wine, and is liable to make him very offensive. This unfortunate | |||

tendency forms one of the greatest dangers that has to be faced | |||

in using Koreans, whether in business, educational or religious | |||

lines. There are brilliant exceptions to this rule, and with better | |||

education and environment there is no reason to suppose that | |||

even the average Korean would preserve so sedulously this un- | |||

. pleasant quality. It is true of Korea as of most countries, that | |||

offensive pride shows itself less among those who have cause for | |||

pride than among those who are trying to establish a claim to it. | |||

It is the impecunious gentleman — the man of good extraction | |||

but indifferent fortune — that tries your patience to the point | |||

of breaking. I was once acquainted with such a person, and he | |||

applied to me for work on the plea of extreme poverty. He was | |||

a gentleman, and would do no work of a merely manual nature, | |||

so I set him to work colouring maps with a brush pen. This is | |||

work that any gentleman can do without shame. But he would | |||

come to my house and bury himself in an obscure corner to do | |||

the work, and would invent all sorts of tricks to prevent his | |||

acquaintances from discovering that he was working. I paid | |||

him in advance for his work, but he soon began to shirk it and | |||

still apply for more money. When I refused to pay more till | |||

he had earned what he had already received, he left in high | |||

dudgeon, established himself in a neighbouring house, and sent | |||

letter after letter, telling me that he was starving. I replied that | |||

he might starve if he wished; that there was money for him if | |||

he would work, and not otherwise. The last note I received | |||

announced that he was about to die, and that he should use all | |||

his influence on the other side of the grave to make me regret | |||

that I had used him so shabbily. I think he did die ; but as that | |||

was fifteen years ago, and I have not yet begun to regret my | |||

action, I fear he is as shiftless in the land of shades as he was | |||

here. This is an extreme but actual case, and could doubtless | |||

be duplicated by most foreigners living in Korea. | |||

The other side of the picture is more encouraging. There is | |||

the best of evidence that a large number of well-born people die | |||

annually of starvation because they are too proud to beg or even | |||

to borrow. This trait is embalmed in almost countless stories | |||

telling of how poor but worthy people, on the verge of starvation, | |||

were rescued from that cruel fate by some happy turn of fortune. | |||

In the city of Seoul there is one whole quarter almost wholly | |||

given up to residences of gentlemen to whom fortune has given | |||

the cold shoulder. It lies under the slopes of South Mountain, | |||

and you need only say of a man that he is a " South Ward | |||

Gentleman " to tell the whole story. Ordinarily the destitute | |||

gentleman does not hesitate to borrow. The changes of for- | |||

tune are so sudden and frequent that he always has a plausible | |||

excuse and can make voluble promises of repayment. To his | |||

credit be it said that if the happy change should come he would | |||

be ready to fulfil his obligations. It has to be recorded, how- | |||

ever, that only a very small proportion of those who borrow from | |||

foreigners ever experience that happy change. There are several | |||

ways to deal with such people: the first is to lend them what | |||

they want; the second is to refuse entirely; and the third is to | |||

do as one foreigner did, — when the Korean asked for the loan | |||

of ten dollars, he took out five and gave them to him, saying, " I | |||

will give this money to you rather than lend you ten. By so doing | |||

I have saved five dollars, and you have gotten that much without | |||

having to burden your memory with the debt." To the ordinary | |||

Korean borrower this would seem like making him a beggar, and | |||

he never would apply to the same source for another loan. | |||

In the matter of truthfulness the Korean measures well up to | |||

the best standards of the Orient, which at best are none too high. | |||

The Chinese are good business men, but their honesty is of the | |||

kind that is based upon policy and not on morals. Among the | |||

common people of that land truthfulness is at a sad discount. | |||

It is largely so in all Far Eastern countries, but there are different | |||

kinds of untruthfulness. Some people lie out of pure malicious- | |||

ness and for the mere fun of the thing. The Koreans do not | |||

belong to this class ; but if they get into trouble, or are faced by | |||

some sudden emergency, or if the success of some plan depends | |||

upon a little twisting of the truth, they do not hesitate to enter | |||

upon the field of fiction. The difference between the Korean and | |||

the Westerner is illustrated by the different ways they will act | |||

if given the direct lie. If you call a Westerner a liar, it is best | |||

to prepare for emergencies ; but in Korea it is as common to use | |||

the expression " You are a liar ! " as it is to say " You don't | |||

say ! " " Is it possible! " or " What, really? " in the West. A | |||

Korean sees about as much moral turpitude in a lie as we see | |||

in a mixed metaphor or a split infinitive. | |||

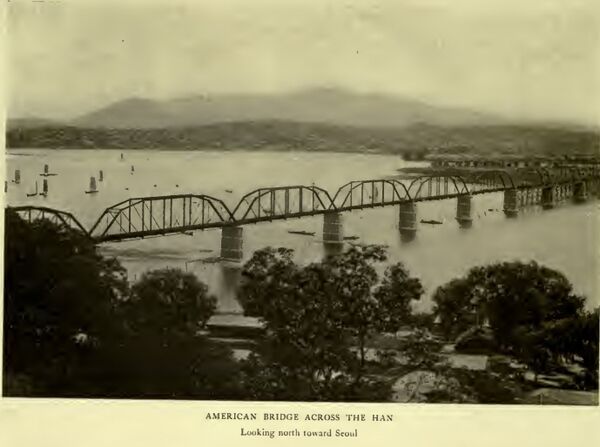

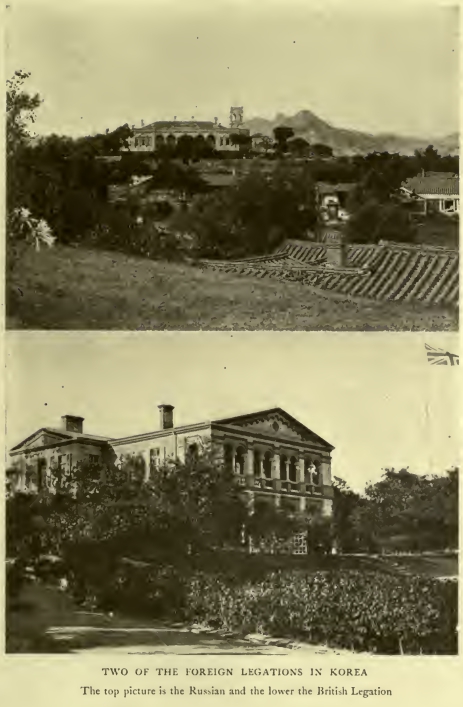

[[파일:04 passing of korea.jpg|600픽셀|섬네일|가운데|A Dancing-Girl Posturing]] | |||

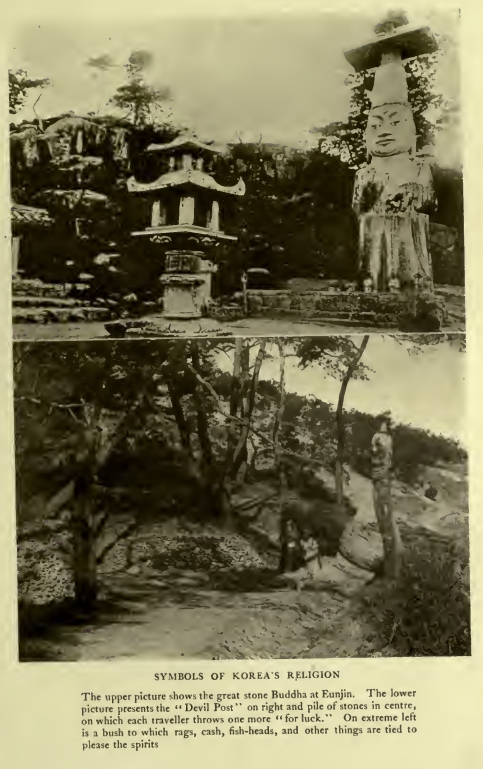

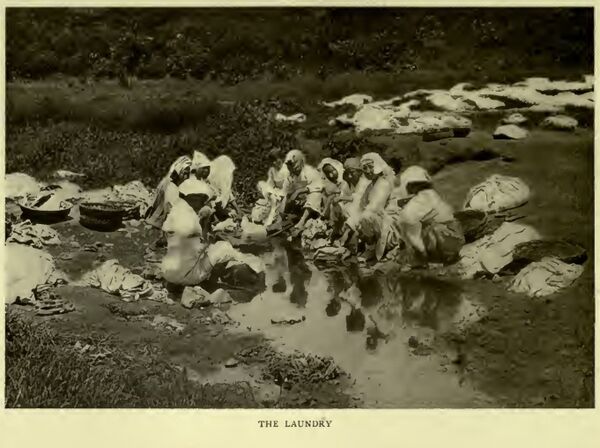

As for morality in its narrower sense, the Koreans allow | |||

themselves great latitude. There is no word for home in their | |||

language, and much of the meaning which that word connotes | |||

is lost to them. So far as I can judge, the condition of Korea | |||

to-day as regards the relations of the sexes is much like that of | |||

ancient Greece in the days of Pericles. There is much similarity | |||

between the kisang (dancing-girl) of Korea and the hctairai of | |||

Greece. But besides this degraded class, Korea is also afflicted | |||

with other and, if possible, still lower grades of humanity, from | |||

which not even the most enlightened countries are free. The | |||

comparative ease with which a Korean can obtain the necessities | |||

of life makes him subject to those temptations which follow in | |||

the steps of leisure and luxury, and the stinging rebuke which a | |||

Japanese envoy administered at a banquet in Seoul in 1591, when | |||