대한제국멸망사

Homer B. Hulbert

New York 1906

PREFACE

MANY excellent books have been written about Korea, each of them approaching the subject from a slightly different angle. In the present volume I have attempted to handle the theme from a more intimate standpoint than that of the casual tourist.

Much that is contained in this present volume is matter that has

come under the writer's personal observation or has been derived

directly from Koreans or from Korean works. Some of this matter

has already appeared in The Korea Review and elsewhere. The

historical survey is a condensation from the writer's " History of

Korea. "

This book is a labour of love, undertaken in the days of Korea's

distress, with the purpose of interesting the reading public in a

country and a people that have been frequently maligned and sel-

dom appreciated. They are overshadowed by China on the one

hand in respect of numbers, and by Japan on the other in respect

of wit. They are neither good merchants like the one nor good

fighters like the other, and yet they are far more like Anglo-Saxons

in temperament than either, and they are by far the pleasantest

people in the Far East to live amongst. Their failings are such as

follow in the wake of ignorance everywhere, and the bettering of

their opportunities will bring swift betterment to their condition.

For aid in the compilation of this book my thanks are mainly

due to a host of kindly Koreans from every class in society, from

the silk-clad yangban to the fettered criminal in prison, from the

men who go up the mountains to monasteries to those who go

down to the sea in ships.

H. B. H.

NEW YORK, 1906.

INTRODUCTORY

THE PROBLEM

There is a peculiar pathos in the extinction of a nation. Especially is this true when the nation is one whose history stretches back into the dim cen- turies until it becomes lost in a labyrinth of myth and legend ; a nation which has played an important part in the moulding of other nations and which is filled with monuments of past achievements. Kija, the founder of Korean civilisation, flourished before the reign of David in Jerusalem. In the fifth century after Christ, Korea enjoyed a high degree of civilisa- tion, and was the repository from which the half-savage tribes of Japan drew their first impetus toward culture. As time went on Japan was so fortunate as to become split up into numerous semi-independent baronies, each under the control of a so-called Daimyo or feudal baron. This resulted, as feudalism every- where has done, in the development of an intense personal loyalty to an overlord, which is impossible in a large state. If one were to examine the condition of European states to-day, he would find that they are enlightened just in proportion as the feudal idea was worked out to its ultimate issues, and wherever, as in southern Europe, the centrifugal power of feudalism was checked by the centripetal power of ecclesiasticism one finds a lower grade of enlightenment, education and genuine liberty. In other words, the feudal system is a chrysalis state from which a people are prepared to leap into the full light of free self- government. Neither China nor Korea has enjoyed that state, and it is therefore manifestly impossible for them to effect any such startling change as that which transformed Japan in a single decade from a cruel and bigoted exclusiveness to an open and enthusiastic world-life. Instead of bursting forth full- winged from a cocoon, both China and Korea must be incu- bated like an egg.

It is worth while asking whether the ultimate results of a

slow and laborious process. like this may not in the end bring

forth a product superior in essential respects to that which fol-

lows the almost magical rise of modern Japan; or, to carry

out the metaphor, whether the product of an egg is not likely

to be of greater value than that of a cocoon. In order to a

clear understanding of the situation it will be necessary to fol-

low out this question to a definite answer. The world has been

held entranced by the splendid military and naval achievements

of Japan, and it is only natural that her signal capacity in war

should have argued a like capacity along all lines. This has

led to various forms of exaggeration, and it becomes the Ameri-

can citizen to ask the question just what part Japan is likely to

play in the development of the Far East. One must study the

factors of the problem in a judicial spirit if he would arrive at

the correct answer. The bearing which this has upon Korea

will appear in due course.

When in 1868 the power of the Mikado or Emperor of

Japan had been vindicated in a sanguinary war against many

of the feudal barons, the Shogunate was done away with once

for all, and the act of centralising the government of Japan

was complete. But in order to guard against insurrection it

was deemed wise to compel all the barons to take up their resi-

dence in Tokyo, where they could be watched. This necessi-

tated the disbanding of the samurai or retainers of the barons.

These samurai were at once the soldiers and the scholars of

Japan. In one hand they held the sword and in the other a

book; not as in medieval Europe, where the knights could but

rarely read and write and where literature was almost wholly

confined to the monasteries. This concentration of physical and

intellectual power in the single class called samurai gave them

far greater prestige among the people at large than was ever

enjoyed by any set of men in any other land, and it conse-

quently caused a wider gulf between the upper and lower classes

than elsewhere, for the samurai shared with no one the fear and

the admiration of the common people. The lower classes cringed

before them as they passed, and a samurai could wantonly kill

a man of low degree almost without fear of consequences.

When the barons were called up to Tokyo, the samurai were

disbanded and were forbidden to wear the two swords which

had always been their badge of office. This brought them face

to face with the danger of falling to the ranks of the lower

people, a fate that was all the more terrible because of the absurd

height to which in their pride they had elevated themselves.

At this precise juncture they were given a glimpse of the

West, with its higher civilisation and its more carefully articu-

lated system of political and social life. With the very genius

of despair they grasped the fact that if Japan should adopt the

system of the West all government positions, whether diplo-

matic, consular, constabulary, financial, educational or judicial,

whether military or civil, would naturally fall to them, and thus

they would be saved from falling to the plane of the common

people. Here, stripped of all its glamour of romance, is the

vital underlying cause of Japan's wonderful metamorphosis.

With a very few significant exceptions it was a purely selfish

movement, conceived in the interests of caste distinction and

propagated in anything but an altruistic spirit. The central

government gladly seconded this proposition, for it immediately

obviated the danger of constant disaffection and rebellion and

welded the state together as nothing else could have done. The

personal fealty which the samurai had reposed in his overlord

was transferred, almost intact, to the central government, and

to-day constitutes a species of national pride which, in the

absence of the finer quality, constitutes the Japanese form of

patriotism.

From that day to this the wide distinction between the upper

and lower classes in Japan has been maintained. In spite of

the fact of so-called popular or representative government, there

can be no doubt that class distinctions are more vitally active

in Japan than in China, and there is a wider social gap between

them than anywhere else in the Far East, with the exception of

India, where Brahmanism has accentuated caste. The reason

for this lies deep in the Japanese character. When he adopted

Western methods, it was in a purely utilitarian spirit. He gave

no thought to the principles on which our civilisation is based.

It was the finished product he was after and not the process.

He judged, and rightly, that energy and determination were

sufficient to the donning of the habiliments of the West, and he

paid no attention to the forces by which those habiliments were

shaped and fitted. The position of woman has experienced no

change at all commensurate with Japan's material transforma-

tion. Religion in the broadest sense is less in evidence than

before the change, for, although the intellectual stimulus of

the West has freed the upper classes from the inanities of the

Buddhistic cult, comparatively few of them have consented to

accept the substitute. Christianity has made smaller advances

in Japan than in Korea herself, and everything goes to prove

that Japan, instead of digging until she struck the spring of

Western culture, merely built a cistern in which she stored up

some of its more obvious and tangible results. This is shown

in the impatience with which many of the best Japanese regard

the present failure to amalgamate the borrowed product with

the real underlying genius of Japanese life. It is one constant

and growing incongruity. And, indeed, if we look at it ration-

ally, would it not be a doubtful compliment to Western culture

if a nation like Japan could absorb its intrinsic worth and enjoy

its essential quality without passing through the long-centuried

struggle through which we ourselves have attained to it? No

more can we enter into the subtleties of an Oriental cult by a

quick though intense study of its tenets. The self-conscious

babblings of a Madam Blavatsky can be no less ludicrous to

an Oriental Pundit than are the efforts of Japan to vindicate

her claim to Western culture without passing through the fur-

nace which made that culture sterling.

The highest praise must be accorded to the earnestness and

devotion of Christian missionaries in Japan, but it is a fact deeply

to be regretted that the results of their work are so closely con-

fined to the upper classes. This fact throws light upon the state-

ment that there is a great gap between the upper and lower classes

there. Even as we are writing, word comes from a keenly observ-

ant traveller in Japan that everywhere the Buddhist temples

are undergoing repairs.

It is difficult to foresee what the resultant civilisation of

Japan will be. There is nothing final as yet, nor have the con-

flicting forces indicated along what definite lines the intense

nationalism of the Japanese will develop.

But let us look at the other side of the picture. Here is

China, and with her Korea, for they are essentially one in gen-

eral temper. They cling with intense loyalty to the past They

are thoroughly conservative. Now, how will you explain it?

Some would say that it is pure obstinacy, a wilful blindness,

an intellectual coma, a moral obsession. This is the easiest, and

superficially the most logical, explanation. It saves time and

trouble; and, after all, what does it matter? It matters much

every way. It does not become us to push the momentous

question aside because those people are contemptible. Four

hundred millions are saved from contempt by their very num-

bers. There is an explanation, and a rational one.

One must not forget that these people are possessed of

a social system that has been worked out through long cen-

turies, and to such fine issues that every individual has his

set place and value. The system is comprehensive, consistent

and homogeneous. It differs widely from ours, but has suf-

ficed to hold those peoples together and give them a national

life of wonderful tenacity. There must be something in

the system fundamentally good, or else it would not have held

together for all these centuries with comparatively so little

modification.

We have seen how the Japanese were shaken out of their

long-centuried sleep by a happy combination of circumstances.

There are doubtless possible combinations which might similarly

affect China and Korea, but the difference in temperament

between them and the Japanese renders it highly improbable that

we shall ever see anything so spectacular as that which occurred

in Japan. No two cults were ever more dissimilar than Con-

fucianism and Buddhism; and if we were to condense into a

single sentence the reason why China and Korea can never follow

Japan's example it would be this : that the Chinese and Korean

temperament followed the materialistic bent of Confucianism,

while the Japanese followed the idealistic bent of Buddhism.

Now, what if the West, instead of merely lending its super-

ficial integuments to China and Korea, should leave all the

harmless and inconsequential customs of those lands intact, and

should attempt instead to reach down to some underlying moral

and fundamental principle and begin a transformation from

within, working outward ; if, instead of carrying on campaigns

against pinched feet and infanticide, we should strike straight

at the root of the matter, and by giving them the secret of

Western culture make it possible for them to evolve a new civ-

ilisation embodying all the culture of the West, but expressed

in terms of Oriental life and habit? Here would be an achieve-

ment to be proud of, for it would prove that our culture is

fundamental, and that it does not depend for its vindication

upon the mere vestments of Western life.

And herein lies the pathos of Korea's position; for, lying

as she does in the grip of Japan, she cannot gain from that

power more than that power is capable of giving — nothing

more than the garments of the West. She may learn science

and industrial arts, but she will use them only as a parrot uses

human speech. There are American gentlemen in Korea who

could lead you to country villages in that land where the fetich

shrines have been swept away, where schools and churches have

been built, and where the transforming power of Christianity

has done a fundamental work without touching a single one

of the time-honoured customs of the land; where hard-handed

farmers have begun in the only genuine way to develop the

culture of the West. That culture evinces itself in its ultimate

forms of honesty, sympathy, unselfishness, and not in the use

of a swallow-tail coat and a silk hat. Which, think you, is the

proper way to go about the rehabilitation of the East? The

only yellow peril possible lies in the arming of the Orient with

the thunder-bolts of the West, without at the same time giving

her the moral forces which will restrain her in their use.

The American public has been persistently told that the

Korean people are a degenerate and contemptible nation, in-

capable of better things, intellectually inferior, and better off

under Japanese rule than independent. The following pages

may in some measure answer these charges, which have been

put forth for a specific purpose, — a purpose that came to full

fruition on the night of November 17, 1905, when, at the point of

the sword, Korea was forced to acquiesce " voluntarily " in the

virtual destruction of her independence once for all. The reader

will here find a narrative of the course of events which led up

to this crisis, and the part that different powers, including the

United States, played in the tragedy.

CHAPTER

1. WHERE AND WHAT KOREA IS ABOVE AND BELOW GROUND

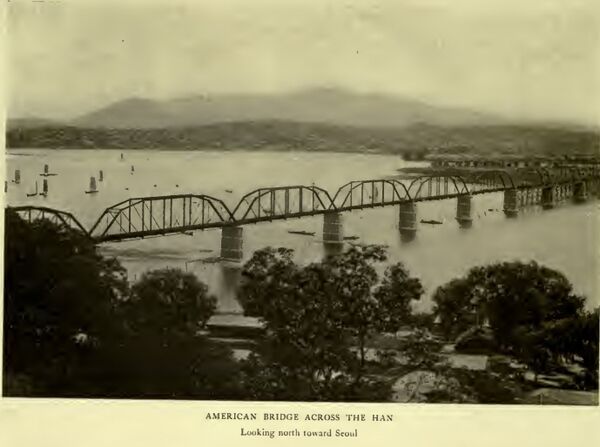

NEAR the eastern coast of Asia, at the forty-fourth parallel of latitude, we find a whorl of mountains culminating in a peak which Koreans call White Head Mountain. From this centre mountain ranges radiate in three directions, one of them going southward and forming the backbone of the Korean peninsula. The water- shed is near the eastern coast, and as the range runs southward it gradually diminishes in height until at last.it is lost in the sea, and there, with its base in the water, it lifts its myriad heads to the surface, and confers upon the ruler of Korea the deserved title of " King of Ten Thousand Islands." A very large part of the arable land of Korea lies on its western side; all the long and navigable rivers are there or in the south; almost all the harbours are on the Yellow Sea. For this reason we may say that topographically Korea lies with her face toward China and her back toward Japan. This has had much to do in determining the history of the country. Through all the centuries she has set her face toward the west, and never once, though under the lash of foreign invasion and threatened ex- tinction, has she ever swerved from her allegiance to her Chinese ideal. Lacordaire said of Ireland that she has remained " free by the soul." So it may be said of Korea, that, although forced into Japan's arms, she has remained " Chinese by the soul."

The climate of Korea may be briefly described as the same

as that of the eastern part of the United States between Maine

and South Carolina, with this one difference, that the prevail-

ing southeast summer wind in Korea brings the moisture from

the warm ocean current that strikes Japan from the south, and

precipitates it over almost the whole of Korea; so that there is

a distinct " rainy season " during most of the months of July

and August. This rainy season also has played an important

part in determining Korean history. Unfortunately for navi-

gation, the western side of the peninsula, where most of the

good harbours are found, is visited by very high tides, and

the rapid currents which sweep among the islands make this

the most dangerous portion of the Yellow Sea. On the eastern

coast a cold current flows down from the north, and makes both

summer and winter cooler than on the western side.

Though the surface of Korea is essentially mountainous, it

resembles Japan very little, for the peninsula lies outside the

line of volcanoes which are so characteristic of the island empire.

Many of the Korean mountains are evidently extinct volcanoes,

especially White Head Mountain, in whose extinct crater now

lies a lake. Nor does Korea suffer at all from earthquakes.

The only remnants of volcanic action that survive are the occa-

sional hot springs. The peninsula is built for the most part

on a granite foundation, and the bare hill-tops, which appear

everywhere, and are such an unwelcome contrast to the foliage-

smothered hills of Japan, are due to the disintegration of the

granite and the erosion of the water during the rainy season.

But there is much besides granite in Korea. There are large

sections where slate prevails, and it is in these sections that the

coal deposits are found, both anthracite and bituminous. It is

affirmed by the Korean people that gold is found in every one

of the three hundred and sixty-five prefectures of the country.

This doubtless is an exaggeration, but it is near enough the

truth to indicate that Korea is essentially a granite formation,

for gold is found, of course, only in connection with such for-

mation. Remarkably beautiful sandstones, marbles and other

building stones are met with among the mountains; and one

town in the south is celebrated for its production of rock crystal,

which is used extensively in making spectacle lenses.

The scenery of Korea as witnessed from the deck of a

steamer is very uninviting, and . it is this which has sent so

many travellers home to assert that this country is a barren,

treeless waste. There is no doubt that the scarcity of timber

along most of the beaten highways of Korea is a certain

blemish, though there are trees in moderate number everywhere ;

but this very absence of extensive forests gives to the scenery

a grandeur and repose which is not to be found in Japanese

scenery. The lofty crags that lift their heads three thousand

feet into the air and almost overhang the city of Seoul are

alpine in their grandeur. There is always distance, openness,

sweep to a Korean view which is quite in contrast to the pic-

turesque coziness of almost all Japanese scenery. This, together

with the crystal atmosphere, make Korea, even after only a few

years' residence, a delightful reminiscence. No people surpass

the Koreans in love for and appreciation of beautiful scenery.

Their literature is full of it. Their nature poems are gems in

their way. Volumes have been written describing the beauties

of special scenes, and Korea possesses a geography, nearly five

hundred years old, in which the beauties of each separate pre-

fecture are described in minute detail, so that it constitutes a

complete historical and scenic guide-book of the entire country.

The vegetable life of Korea is like that of other parts of

the temperate zone, but there is a striking preponderance of a

certain kind of pine, the most graceful of its tribe. It forms

a conspicuous element in every scene. The founder of the

dynasty preceding the present one called his capital Song-do,

or Pine Tree Capital. It is a constant theme in Korean art,

and plays an important part in legend and folk-lore in general.

Being an evergreen, it symbolises eternal existence. There are

ten things which Koreans call the chang sang pul sa, or " long-

lived and deathless." They are the pine-tree, tortoise, rock,

stag, cloud, sun, moon, stork, water and a certain moss or

lichen named " the ageless plant." Pine is practically the only

wood used in building either houses, boats, bridges or any other

structure. In poetry and imaginative prose it corresponds to the

oak of Western literature. Next in importance is the bamboo,

which, though growing only in the southern provinces, is used

throughout the land and in almost every conceivable way. The

domestic life of the Korean would be thrown into dire confu-

sion were the bamboo to disappear. Hats are commonly made

of it, and it enters largely, if not exclusively, into the con-

struction of fans, screens, pens, pipes, tub-hoops, flutes, lanterns,

kites, bows and a hundred other articles of daily use. Take

the bamboo out of Korean pictorial art and half the pictures in

the land would be ruined. From its shape it is the symbol of

grace, and from its straightness and the regular occurrence of

its nodes it is the symbol of faithfulness. The willow is one

of the most conspicuous trees, for it usually grows in the vicinity

of towns, where it has been planted by the hand of man. Thus

it becomes the synonym of peace and contentment. The mighty

row of willows near Pyeng-yang in the north is believed to

have been planted by the great sage and coloniser Kija in

1 122 B. c., his purpose being to influence the semi-savage people

by this object-lesson. From that time to this Pyeng-yang has

been known in song and story as " The Willow Capital." As

the pine is the symbol of manly vigour and strength, so the

willow is the synonym of womanly beauty and grace. Willow

wood, because of its lightness, is used largely in making the

clumsy wooden shoes which are worn exclusively in wet weather ;

and chests are made of it when lightness is desirable. The

willow sprays are used in making baskets of all kinds, so that .

this tree is, in many ways, quite indispensable. Another useful

wood is called the paktal. It has been erroneously called the

sandal-wood, which it resembles in no particular. It is very

like the iron-wood of America, and is used in making the

laundering clubs, tool handles, and other utensils which require

great hardness and durability. It was under a paktal-tree that

the fabled sage Tangun was found seated some twenty-three

hundred years before Christ; so it holds a peculiar place in

Korean esteem. As the pine was the dynastic symbol of Koryu,

918-1392, so the plum-tree is the symbol of this present dynasty.

It was chosen because the Chinese character for plum is the

same as that of the family name of the reigning house. It

was for this cogent reason that the last king of the Koryu

dynasty planted plum-trees on the prophetic site of the present

capital, and then destroyed them all, hoping thereby to blight

the prospects of the Yi family, who, prophecy declared, would

become masters of the land.

There are many hard woods in Korea that are used in the

arts and industries of the people. Oak, ginko, elm, beech and

other species are found in considerable numbers, but the best

cabinet woods are imported from China. An important tree,

found mostly in the southern provinces, is the paper-mulberry,

broussonetai papyrifcra, the inner bark of which is used exclu-

sively in making the tough paper used by Koreans in almost

every branch of life. It is celebrated beyond the borders of the

peninsula, and for centuries formed an important item in the

annual tribute to China and in the official exchange of goods

with Japan. It is intrinsically the same as the superb Japanese

paper, though of late years the Japanese have far surpassed

the Koreans in its manufacture. The cedar is not uncommon

in the country, but its wood is used almost exclusively for

incense in the Buddhist monasteries. Box-wood is used for

making seals and in the finer processes of the xylographic art,

but for this latter purpose pear-wood is most commonly

substituted.

Korea is richly endowed with fruits of almost every kind

common to the temperate zone, with the exception of the apple.

Persimmons take a leading place, for this is the one fruit that

grows to greater perfection in this country than in any other

place. They grow to the size of an ordinary apple, and after

the frost has touched them they are a delicacy that might be

sought for in vain on the tables of royalty in the West. The

apricot, while of good flavour, is smaller than the European

or American product. The peaches are of a deep red colour

throughout and are of good size, but are not of superior quality.

Plums are plentiful and of fair quality. A sort of bush cherry

is one of the commonest of Korean fruits, but it is not grown

by grafting and is inferior in every way. Jujubes, pomegran-

ates, crab-apples, pears and grapes are common, but are gen-

erally insipid to Western taste. Foreign apples, grapes, pears,

peaches, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, currants and

other garden fruits grow to perfection in this soil. As for

nuts, the principal kinds are the so-called English walnuts,

chestnuts and pine nuts. We find also ginko and other nuts,

but they amount to very little.

The question of cereals is, of course, of prime importance.

The Korean people passed immediately from a savage con-

dition to the status of an agricultural community without the

intervention of a pastoral age. They have never known any-

thing about the uses of milk or any of its important products,

excepting as medicine. Even the primitive legends do not ante-

date the institution of agriculture in the peninsula. Rice was

first introduced from China in 1122 u. c., but millet had already

been grown here for many centuries. Rice forms the staple

article of food of the vast majority of the Korean people. In

the northern and eastern provinces the proportion of other

grains is more considerable, and in some few places rice is

hardly eaten at all; but the fact remains that, with the excep-

tion of certain mountainous districts where the construction of

paddy-fields is out of the question, rice is the main article of

food of the whole nation. The history of the introduction

and popularisation of this cereal and the stories and poems that

have been written about it would make a respectable volume.

The Korean language has almost as many synonyms for it as

the Arabic has for horse. It means more to him than roast

beef does to an Englishman, macaroni to an Italian, or potatoes

to an Irishman. There are three kinds of rice in Korea. One

is grown in the water, another in ordinary fields, and another

still on the sides of hills. The last is a smaller and harder

variety, and is much used in stocking military granaries, for it

will last eight or ten years without spoiling. The great enemies

of rice are drought, flood, worms, locusts, blight and wind.

The extreme difficulty of keeping paddy-fields in order in such

a hilly country, the absolute necessity of having rains at a par-

ticular time and of not having it at others, the great labour of

transplanting and constant cultivation, — all these things con-

spire to make the production of rice an incubus upon the Korean

people. Ask a Louisiana rice-planter how he would like to

cultivate the cereal in West Virginia, and you will discover

what it means in Korea. But in spite of all the difficulties,

the Korean clings to his favourite dish, and out of a hundred

men who have saved up a little money ninety-nine will buy

rice-fields as being the safest investment. Korean poetry teems

with allusions to this seemingly prosaic cereal. The following

is a free translation of a poem referring to the different species

of rice:

Was measured out, mile beyond mile afar;

The smiling face which Chosun first upturned

Toward the o'er-arching sky is dimpled still

With that same smile ; and nature's kindly law,

In its unchangeability, rebukes

The fickle fashions of the thing called Man.

The mountain grain retains its ancient shape,

Long-waisted, hard and firm ; the rock-ribbed hills,

On which it grows, both form and fibre yield.

The lowland grain still sucks the fatness up

From the rich fen, and delves for gold wherewith

To deck itself for Autumn's carnival.

Alas for that rude swain who nothing recks

Of nature's law, and casts his seedling grain

Or here or there regardless of its kind.

For him the teeming furrow gapes in vain

And dowers his granaries with emptiness.

To north and south the furrowed mountains stretch,

A wolf gigantic, crouching to his rest.

To east and west the streams, like serpents lithe,

Glide down to seek a home beneath the sea.

The South — warm mother of the race — pours out

Her wealth in billowy floods of grain. The North —

Stern foster-mother — yields her scanty store

By hard compulsion ; makes her children pay

For bread by mintage of their brawn and blood.

Millet is the most ancient form of food known in Korea,

and it still forms the staple in most places where rice will not

grow. There are many varieties of millet, all of which flourish

luxuriantly in every province. It is a supplementary crop, in

that it takes the place of rice when there is a shortage in that

cereal owing to drought or other cause. Barley is of great

importance, because it matures the earliest in the season, and so

helps the people tide over a period of scarcity. A dozen vari-

eties of beans are produced, some of which are eaten in con-

nection with rice, and others are fed to the cattle. Beans form

one of the most important exports of the country. Wheat is

produced in considerable quantities in the northern provinces.

Sesamum, sorghum, oats, buckwheat, linseed, corn and a few

other grains are found, but in comparatively small quantities.

As rice is the national dish, we naturally expect to find

various condiments to go with it. Red-peppers are grown

everywhere, and a heavy kind of lettuce is used in making

the favourite sauerkraut, or kimchi, whose proximity is detected

•without the aid of the eye. Turnips are eaten raw or pickled.

A kind of water-cress called minari plays a secondary part

among the- side dishes. In the summer the people revel in

melons and canteloupes, which they eat entire or imperfectly

peeled, and even the presence of cholera hardly calls a halt to

this dangerous indulgence. Potatoes have long been known to

the Koreans, and in a few mountain sections they form the

staple article of diet. They are of good quality, and are largely

eaten by foreign residents in the peninsula. Onions and garlic

abound, and among the well-to-do mushrooms of several vari-

eties are eaten. Dandelions, spinach and a great variety of

salads help the rice to " go down."

Korea is celebrated throughout the East for its medicinal

plants, among which ginseng, of course, takes the leading place.

The Chinese consider the Korean ginseng far superior to any

other. It is of two kinds, — the mountain ginseng, which is so

rare and precious that the finding of a single root once in

three seasons suffices the finder for a livelihood; and the ordi-

nary cultivated variety, which differs little from that found in

the woods in America. The difference is that in Korea it is

carefully cultivated for six or seven years, and then after being

gathered it is put through a steaming process which gives it

a reddish tinge. This makes it more valuable in Chinese esteem,

and it sells readily at high prices. It is a government monopoly,

and nets something like three hundred thousand yen a year.

Liquorice root, castor beans and scores of other plants that

figure in the Western pharmacopoeia are produced, together

with many that the Westerner would eschew.

The Koreans are great lovers of flowers, though compara-

tively few have the means to indulge this taste. In the spring

the hills blush red with rhododendrons and azaleas, and the

ground in many places is covered with a thick mat of violets.

The latter are called the " savage flower," for the lobe is sup-

posed to resemble the Manchu queue, and to the Korean every

Alanchu is a savage. The wayside bushes are festooned with

clematis and honeysuckle, the alternate white and yellow blossoms

of the latter giving it the name " gold and silver flower." The

lily-of-the-valley grows riotously in the mountain dells, and

daffodils and anemones abound. The commonest garden flower

is the purple iris, and many official compounds have ponds

in which the lotus grows. The people admire branches of

peach, plum, apricot or crab-apple as yet leafless but cov-

ered with pink and white flowers. The pomegranate, snow-

ball, rose, hydrangea, chrysanthemum and many varieties of

lily figure largely among the favourites. It is pathetic to

see in the cramped and unutterably filthy quarters of the

very poor an effort being made to keep at least one plant

alive. There is hardly a hut in Seoul where no flower is

found.

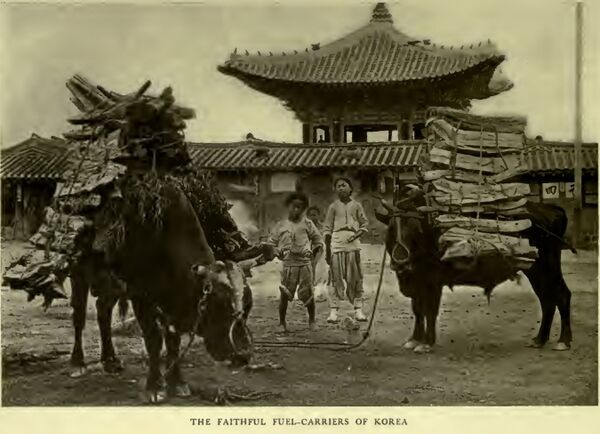

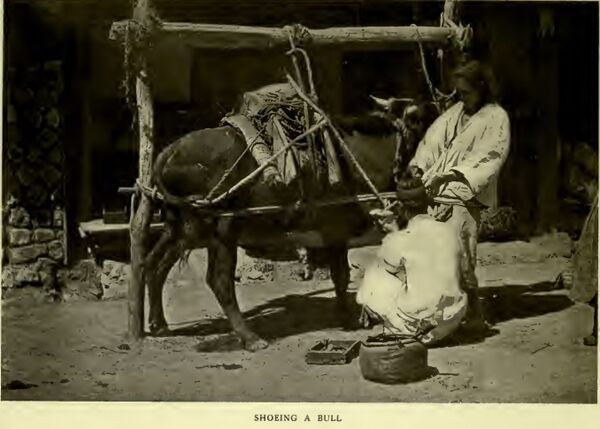

As for animal life, Korea has a generous share. The mag-

nificent bullocks which carry the heavy loads, draw the carts and

pull the ploughs are the most conspicuous. It is singular that

the Koreans have never used milk or any of its products, though

the cow has existed in the peninsula for at least thirty-five

hundred years. This is one of the proofs that the Koreans

have never been a nomadic people. Without his bullock the

farmer would be all at sea. No other animal would be able to

drag a plough through the adhesive mud of a paddy-field. Great

mortality among cattle, due to pleuro-pneumonia, not infre-

quently becomes the main cause of a famine. There are no

oxen in Korea. Most of the work is done with bullocks, which

are governed by a ring through the nose and are seldom

obstreperous. Every road in Korea is rendered picturesque by

long lines of bullocks carrying on their backs huge loads of

fuel in the shape of grass, fagots of wood or else fat bags

of rice and barley. As might be expected, cowhides are an

important article of export.

The Korean pony is unique, at least in Eastern Asia. It

is a little larger than the Shetland pony, but is less heavily

built. Two thousand years ago, it is said, men could ride these

animals under the branches of the fruit trees without lowering

the head. They differ widely from the Manchu or Japanese

horse, and appear to be indigenous — unless we may believe the

legend that when the three sages arose from a fissure in the

ground in the island of Quelpart three thousand years ago,

each of them found a chest floating in from the south and

containing a colt, a calf, a pig, a dog and a wife. The pony

is not used in ploughing or drawing a cart, for it is not heavy

enough for such work, but it is used under the pack and under

the saddle, frequently under both, for often the traveller packs

a huge bundle on the pony and then seats himself on top, so

that the animal forms but a vulgar fraction of the whole

ensemble. Foreigners of good stature frequently have to raise

the feet from the stirrup when riding along stony roads. Yet

these insignificant beasts are tough and long-suffering, and will

carry more than half their own weight thirty-five miles a day,

week in and week out.

As in all Eastern countries, the pig is a ubiquitous social

factor. We use the word " social " advisedly, for in country vil-

lages at least this animal is always visible, and frequently under

foot. It is a small black breed, and is so poorly fed as to have

practically no lateral development, but resembles the " razor-

backs " of the mountain districts of Tennessee. Its attenuated

shape is typical of the concentrated character of its porcine

obstinacy, as evidenced in the fact that the shrewd Korean

farmer prefers to tie up his pig and carry it to market on

his own back rather than drive it on foot.

Korea produces no sheep. The entire absence of this animal,

except as imported for sacrificial purposes, confirms the suppo-

sition that the Koreans have never been a pastoral people.

Foreigners have often wondered why they do not keep sheep

and let them graze on the uncultivable hillsides which form

such a large portion of the area of the country. The answer

is manifold. Tigers, wolves and bears would decimate the

flocks. All arable land is used for growing grain, and what

grass is cut is all consumed as fuel. It would therefore be

impossible to winter the sheep. Furthermore, an expert sheep

man, after examining the grasses common on the Korean hill-

sides, told the writer that sheep could not eat them. The turf

about grave sites and a few other localities would make good

grazing for sheep, but it would be quite insufficient to feed any

considerable number even in summer.

The donkey is a luxury in Korea, being used only by well-

to-do countrymen in travelling. Its bray is out of all propor-

tion to its size, and one really wonders how its frame survives

the wrench of that fearful blast.

Reputable language is hardly adequate to the description of

the Korean dog. No family would be complete without one;

but its bravery varies inversely as the square of its vermin,

which is calculable in no known terms. This dog is a wolfish

breed, but thoroughly domesticated. Almost every house has

a hole in the front door for his accommodation. He will lie

just inside, with his head protruding from the orifice and his

eyes rolling from side to side in the most truculent manner. If

he happens to be outside and you point your finger at him,

he rushes for this hole, and bolts through it at a pace which

seems calculated to tear off all the hair from his prominent

angles. Among certain of the poorer classes the flesh of the

dog is eaten, and we have in mind a certain shop in Seoul

where the purveying of this delicacy is a specialty. We once

shot a dog which entertained peculiar notions about the privacy

of our back yard. The gateman disposed of the remains in a

mysterious manner and then retired on the sick-list for a few

days. When he reappeared at last, with a weak smile on his

face he placed his hand on his stomach and affirmed with evi-

dent conviction that some dogs are too old for any use. But,

on the whole, the Korean dog is cleared of the charge of use-

lessness by the fact that he acts as scavenger in general, and

really does much to keep the city from becoming actually

uninhabitable.

The cat is almost exclusively of the back-fence variety, and

is an incorrigible thief. It is the natural prey of the ubiquitous

dog and the small boy. Our observation leads us to the sad

but necessary conclusion that old age stands at the very bottom

of the list of causes of feline mortality.

So much for domestic animals. Of wild beasts the tiger

takes the lead. The general notion that this animal is found

only in tropical or semi-tropical countries is a mistake. The

colder it is and the deeper the snow, the more he will be in evi-

dence in Korea. Country villages frequently have a tiger trap

of logs at each end of the main street, and in the winter time

these are baited with a live animal, — pig for choice. The tiger

attains a good size, and its hair is thick and long. We have seen

skins eleven and a half feet long, with hair two inches and more

in length. This ugly beast will pass through the streets of a

village at night in the dead of winter, and the people are fortu-

nate if he does not break in a door and carry away a child. No

record is kept of the mortality from this cause, but it is probable

that a score or more of people perish annually in this way.

Legend and story are full of the ravages of the tiger. He is

supposed to be able to imitate the human voice, and thus lure

people out of their houses at night. Koreans account for the

fierceness of his nature by saying that in the very beginning of

things the Divine Being offered a bear and a tiger the opportunity

of becoming men if they would endure certain tests. The bear

passed the examination with flying colours, but the tiger suc-

cumbed to the trial of patience, and so went forth the greatest

enemy of man.

Deer are common throughout the land, and at the proper

season they are eagerly sought for because of their soft horns,

which are considered of great medicinal value. Wealthy Koreans

who are ailing often go among the mountains with the hope of

being in at the death of a young buck, and securing a long

draught of the warm blood, which they look upon as nearly

equivalent to the fountain of eternal youth. The exercise required

for this is in itself enough to make an ill man well, so the fiction

about the blood is not only innocent but valuable.

The bear is found occasionally, but is of a small breed and

does comparatively little damage. The wild boar is a formidable

animal, and is considered fully as dangerous to meet as the tiger,

because it will charge a supposed enemy at sight. We have seen

specimens weighing well toward four hundred pounds and with

formidable tushes. The fox is found in every town and district

in the country. It is the most detested of all things. It is the

epitome of treachery, meanness and sin. The land is full of

stories of evil people who turned out to be foxes in the disguise

of human form. And of all foxes the white one is the worst,

but it is doubtful whether such has ever been seen in Korea. Tra-

dition has no more opprobrious epithet than " fox." Even the

tiger is less dangerous, because less crafty. The wolf is com-

paratively little known, but occasionally news comes from some

distant town that a child has been snatched away by a wolf.

The leopard is another supposedly tropical animal that flour-

ishes in this country. Its skin is more largely used than that

of the tiger, but only officials of high rank are allowed the

luxury.

Among lesser animals are found the badger, hedgehog,

squirrel, wildcat, otter, weasel and sable. The last is highly

prized for its skin, but it is of poorer quality than that of the

Siberian sable. At the same time many handsome specimens

have been picked up here. The Koreans value most highly the

small spot of yellow or saffron that is found under the throat

of the sable. We have seen whole garments made of an almost

countless number of such pieces. Naturally it takes a small for-

tune to acquire one of them.

For its bird life, especially game birds, Korea is deservedly

famous. First comes the huge bustard, which stands about four

feet high and weighs, when dressed, from twenty to thirty

pounds. It is much like the wild turkey, but is larger and gamier.

The beautiful Mongolian pheasant is found everywhere in the

country, and in winter it is so common in the market that it

brings only half the price of a hen. Within an hour of Seoul

one can find excellent pheasant shooting at the proper season.

Ducks of a dozen varieties, geese, swan and other aquatic birds

abound in such numbers that one feels as if he were taxing the

credulity of the reader in describing them. In the winter of 1891

the ducks migrated apparently in one immense flock. Their

approach sounded like the coming of a cyclone, and as they

passed, the sky was completely shut out from view. It would

have been impossible to get a rifle bullet between them. They

do not often migrate this way, but flocks of them can be seen in

all directions at almost any time of day during the season. Even

as we write, information comes that a party of three men

returned from two days' shooting with five hundred and sixty

pounds of birds. Quail, snipe and other small birds are found

in large quantities, but the hunter scorns them in view of the

larger game. Various kinds of storks, cranes and herons find

abundance of food in the flooded paddy-fields, where no one

thinks of disturbing them. One of the sights of Seoul is its airy

scavengers, the hawks, who may be seen sometimes by the score

sailing about over the town. Now and again one of them will

sweep down and seize a piece of meat from a bowl that a woman

is carrying home on her head. It is not uncommon to see small

boys throwing dead mice into the air to see the hawks swoop

down and seize them before they reach the ground.

Korea contains plenty of snakes, but none of them are spe-

cially venomous, although there are some whose bite will cause

considerable irritation. Many snakes live among the tiles of

the roofs, where they subsist on the sparrows that make their

nests under the eaves. These snakes are harmless fellows, and

when you see one hanging down over your front door in the

dusk of evening it should cause no alarm. The people say, and

believe it too, that if a snake lives a thousand years it assumes

a short and thick shape and acquires wings, with which it flies

about with inconceivable rapidity, and is deadly not only because

of its bite, but if a person even feels the wind caused by its light-

ning flash as it speeds by he will instantly die. Formerly,

according to Korean tradition, there were no snakes in Korea;

but when the wicked ruler Prince Yunsan (1495-1506) had

worn himself out with a life of excesses, he desired to try the

effect of keeping a nest of snakes under his bed, for he had heard

that this would restore lost vitality. So he sent a boat to India,

and secured a cargo of selected ophidians, and had them brought

to Korea. The cargo was unloaded at Asan; but it appears

that the stevedores had not been accustomed to handle this kind

of freight, and so a part of the reptiles made their escape into

the woods. From that time; so goes the tale, snakes have existed

here as elsewhere. Unfortunately no one has ever made a study

of serpent worship in Korea, but there appears to be some reason

to believe that there was once such a cult. The Koreans still

speak of the op-kuregi, or " Good Fortune Serpent " ; and as

most of the natives have little other religion than that of praying

to all kinds of spirits for good luck, it can hardly be doubted that

the worship of the serpent in some form has existed in Korea.

Though there are no deadly snakes in the country, there are

insects that annually cause considerable loss of life. The centi-

pede attains a growth of six or seven inches, and a bite from one

of them may prove fatal, if not attended to at once. The Koreans

cut up centipedes and make a deadly drink, which they use, as

hemlock was used in Greece, for executing criminals. This has

now gone out of practice, however, thanks to the enlightening

contact with Westerners, who simply choke a man to death with

a rope ! Among the mountains it is said that a poisonous spider

is found ; but until this is verified we dare not vouch for it.

The tortoise plays an important part in Korean legend and

story. He represents to the Korean mind the principle of healthy

conservatism. He is never in a hurry, and perhaps this is why

the Koreans look upon him with such respect, if not affection.

All animals in Korea are classed as good or bad. We have

already said that the fox is the worst. The tiger, boar, frog and

mouse follow. These are all bad ; but the bear, deer, tortoise,

cow and rabbit are all good animals.

More important than all these, except cattle, are the fish of

Korea. The waters about the peninsula swarm with fish of a

hundred kinds. They are all eaten by the people, even the sharks

and the octopi. The commonest is the ling, which is caught in

enormous numbers off the east coast, and sent all over the country

in the dried form. Various kinds of clams, oysters and shrimps

are common. Whales are so numerous off the eastern coast that

a flourishing Japanese company has been employed in catching

them of late years. Pearl oysters are found in large numbers

along the southern coast, and the pearls would be of considerable

value if the Koreans knew how to abstract them from the shells

in a proper manner.

But fish and pearls are not the only sea-products that the

Korean utilises. Enormous quantities of edible seaweed are

gathered, and the sea-slug, or beche-de-mer, is a particular deli-

cacy. The Koreans make no use of those bizarre dishes for

which the Chinese are so noted, such as birds' nests and the like.

Their only prandial eccentricity is boiled dog, and that is strictly

confined to the lowest classes.

2. THE PEOPLE

study of the origin and the ethnological affinities of the Korean people is yet in its infancy. Not until a close and exhaustive investigation has been made of the monuments, the folk-lore, the language and all the other sources of information can anything be said defi- nitely upon this question. It will be in place, therefore, to give here the tentative results already arrived at, but without dogmatising.

Oppert was the first to note that in Korea there are two types

of face, — the one distinctly Mongolian, and the other lacking

many of the Mongolian features and tending rather to the Malay

type. To the new-comer all Koreans look alike; but long resi-

dence among them brings out the individual peculiarities, and

one comes to recognise that there are as many kinds of face here

as in the West. Dr. Baelz, one of the closest students of Far

Eastern physiognomy, recognises the dual nature of the Korean

type, and finds in it a remarkable resemblance to a similar feature

of the Japanese, among whom we learn that there is a certain

class, probably descendants of the ancient Yamato race, which

has preserved to a great extent the same non-Mongolian cast of

features. This seems to have been overlaid at some later time

by a Polynesian stock. The ethnological relation between the

non-Mongolian type in Korea and the similar type in Japan is

one of the most interesting racial problems of the Far East.

I feel sure that it is the infusion of this type into Korea and Japan

that has differentiated these peoples so thoroughly from the

Chinese.

Five centuries before Christ, northern Korea and southern

Korea were very clearly separated. The Kija dynasty in the

north had consolidated the people into a more or less homo-

geneous state, but this kingdom never extended south further

than the Han River. At this time the southern coast of the

peninsula was peopled by a race differing in essential particulars

from those of the north. Their language, social system, govern-

ment, customs, money, ornaments, traditions and religion were

all quite distinct from those of the north. Everything points

to the belief that they were maritime settlers or colonists, and

that they had come to the shores of Korea from the south.

The French missionaries in Korea were the first to note a

curious similarity between the Korean language and the lan-

guages of the Dravidian peoples of southern India. It is well

established that India was formerly inhabited by a race closely

allied to the Turanian peoples, and that when the Aryan con-

querors swept over India the earlier tribes were either driven in

flight across into Burmah and the Malay Peninsula, or were

forced to find safety among the mountains in the Deccan. From

the Malay Peninsula we may imagine them spreading in various

directions. Some went north along the coast, others into the

Philippine Islands, then to Formosa, where Mr. Davidson, the

best authority, declares tHat the Malay type prevails. The power-

ful " Black Current," the Gulf Stream of the Pacific, naturally

swept northward those who were shipwrecked. The Liu-Kiu

Islands were occupied, and the last wave of this great dispersion

broke on the southern shores of Japan and Korea, leaving there

the nucleus of those peoples who resemble each other so that if

dressed alike they cannot be distinguished as Japanese or Korean

even by an expert. The small amount of work that has been

so far done indicates a striking resemblance between these south-

ern Koreans and the natives of Formosa, and the careful com-

parison of the Korean language with that of the Dravidian

peoples of southern India reveals such a remarkable similarity,

phonetic, etymologic, and syntactic, that one is forced to recognise

in it something more than mere coincidence. The endings of

many of the names of the ancient colonies in southern Korea are

the exact counterpart of Dravidian words meaning " settlement "

or " town." The endings -caster and -coin in English are no

more evidently from the Latin than these endings in Korea are

from the Dravidian.

The early southern Koreans were wont to tattoo their bodies.

The custom has died out, since the more rigorous climate of the

peninsula compels the use of clothing covering the whole body.

The description of the physiological features of those Dravidian

tribes which have suffered the least from intermixture with others

coincides in every particular with the features of the Korean.

Of course it is impossible to go into the argument in cxtenso

here; but the most reasonable conclusion to be arrived at to-day

is that the peninsula of Korea is inhabited by two branches

of the same original family, a part of which came around

China by way of the north, and the other part by way of the

south.

As we see in the historical review given elsewhere in these

pages, the southern kingdom of Silla was the first to obtain

control of the entire peninsula and impose her laws and language,

and it is for this reason that the language to-day reflects much

more of the southern stock than of the northern.[1]

CHARACTERISTICS

In discussing the temperament and the mental characteristics of the Korean people, it will be necessary to begin with the trite saying that human nature is the same the world over. The new- comer to a strange country like this, where he sees so many curious and, to him, outlandish things, feels that the people are in some way essentially different from himself, that they suffer from some radical lack; but if he were to stay long enough to learn the language, and get behind the mask which hides the genuine Korean from his mental view, he would find that the Korean might say after old Shylock, " I am a Korean. Hath not a Korean eyes? Hath not a Korean hands, organs, dimen- sions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons? subject to the same diseases? healed with the same means ? warmed and cooled by the same summer and winter as the Westerner is ? If you prick us, do we not bleed ? If you tickle us, do we not laugh ? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not be revenged? " In other words, he will find that the differences between the Oriental and the Occidental are wholly superficial, the outcome of training and environment, and not of radical dissimilarity of temperament. But there is this to be said: it is far easier to get close to a Korean and to arrive at his point of view than to get close to a Japanese or a Chinese. Somehow or other there seems to be a greater temperamental difference between the Japanese or Chinese and the Westerner than between the Korean and the Westerner. I believe the reason for this lies in the fact of the different balance of temperamental qualities in these different peoples. The Japanese are a people of sanguine temperament. They are quick, versatile, idealistic, and their temperamental sprightliness approaches the verge of volatility. This quality stood them in good stead when the opportunity came for them to make the great volte face in 1868. It was a happy leap in the dark. In the very same way the Japanese often embarks upon business enterprises, utterly sanguine of success, but without forecasting what he will do in case of disaster. The Chinese, on the other hand, while very superstitious, is comparatively phlegmatic. He sees no rainbows and pursues no ignes fatui. He has none of the martial spirit which impels the Japanese to deeds of patriotic daring. But he is the best business man in the world. He is careful, patient, persevering, and content with small but steady gains. No one knows better than he the ultimate evil results of breaking a contract. Without laying too much emphasis upon these opposite tendencies in the Japanese and Chinese, we may say that the former lean toward the idealistic, while the latter lean toward the utilitarian. The temperament of the Korean lies midway between the two, even as his country lies between Japan and China. This combination of qualities makes the Korean rationally idealistic. Those who have seen the Korean only superficially, and who mark his unthrifty habits, his happy-go-lucky methods, his narrowness of mind, will think my characterisation of him flattering ; but those who have gone to the bottom of the Korean character, and are able to distin- guish the true Korean from some of the caricatures which have been drawn of him, will agree that there is in him a most happy combination of rationality and emotionalism. And more than this, I would submit that it is the same combination that has made the Anglo-Saxon what he is. He is at once cool-headed and hot-headed. He can reason calmly and act at white heat. It is this welding of two different but not contrary characteris- tics that makes the power of the Anglo-Saxon peoples. It will be necessary to show, therefore, why it is that Korea has done so little to justify the right to claim such exceptional qualities. But before doing this, I would adduce a few facts to show on what my claim is based.

In the first place, it is the experience of those who have had

to do with the various peoples of the Far East that it is easier

to understand the Korean and get close to him than it is to

understand either the Japanese or the Chinese. He is much more

like ourselves. You lose the sense of difference very readily, and

forget that he is a Korean and not a member of your own race.

This in itself is a strong argument; for it would not be so if

there were not some close intellectual, or moral, or tempera-

mental bond of sympathy. The second argument is a religious

one. The religions of China were forced upon Korea irrespective

of her needs or desires. Confucianism, while apparently satis-

factory to a man utterly devoid of imagination (a necessary

instrument to be used in the work of unifying great masses of

population, by anchoring them to the dead bones of their ances-

tors), can be nothing less than contemptible to a man possessed

of actual humour. Two things have preserved the uniform politi-

cal solidarity of the Chinese Empire for the last three thousand

years, — the sacred ideograph and the ancestral grave. But

Confucianism is no religion ; it is simply patriarchal law. That

law, like all other civil codes, received its birth and nutriment

from the body politic of China by natural generation. But the

Korean belongs to a different intellectual and temperamental

species, and thus the law which was bone of China's bone and

flesh of her flesh was less than a foster-child to Korea. Its

entire lack of the mystical element renders it quite incapable of

satisfying the religious cravings of such a people as the Koreans.

Buddhism stands at the opposite pole from Confucianism. It is

the most mystical of all cults outside the religion of the Nazarene.

This is why it has become so strongly intrenched in Japan. While

Confucianism leaves nothing to the imagination, Buddhism

leaves everything. The idealism of the, Japanese surrendered to

it, and we may well believe that when Buddhism is driven to bay

it will not be at Lhasa, the home of the Lamas, but at Nara or

at Nikko. Here again that rational side of the Korean tempera-

ment came in play. While Confucianism contained too little

mysticism for him, Buddhism contained too much ; and so, while

nominally accepting both, he made neither of them a part of

himself.

It is said that when a company of Tartar horsemen capture

one of the enemy they bury him to the neck in the earth, pack the

dirt firmly about him so that he can move neither hand nor foot,

place a bowl of water and a bowl of food just before his face,

and leave him to die of hunger, thirst or sunstroke, or to be

torn by wolves. This is the way, metaphorically, in which Korea

was treated to religions. Both kinds were placed before her very

face, but she could partake of neither. The sequel is important.

The Christian religion was introduced into Korea by the Roman

Catholics about a century ago, and by Protestants two decades

ago. The former made considerable advance in spite of terrible

persecution, but their rate of advance was slow compared with

what has been done by the Protestant missionaries. I make bold

to say that the Christian religion, shorn of all trappings and

embellishments of man's making, appeals perfectly to the ration-

ally emotional temperament of the Korean. And it is to some

extent this perfect adaptability which has won for Christianity

such a speedy and enthusiastic hearing in this country. Chris-

tianity is at once the most rational and the most mystical of reli-

gions, and as such is best fitted, humanly speaking, to appeal to

this people. This, of course, without derogation from its uni-

versal claims. One has but to consult the records of modern

missions to see what a wonderful work has been done in this

land by men who are presumably no more and no less devoted

than those at work in other fields.

Being possessed, then, of a temperament closely allied to that

of the Anglo-Saxon, what has caused the present state of intel-

lectual and moral stagnation? Why is it that most people look

upon the Korean as little better than contemptible? It is because

in the sixth and seventh centuries, when Korea was in her forma-

tive stage, when she was just ready to enter upon a career of inde-

pendent thought and achievement, the ponderous load of Chinese

civilisation was laid upon her like an incubus. She knew no

better than to accept these Chinese ideals, deeming in her igno-

rance that this would be better than to evolve ideals of her own.

From that time to this she has been the slave of Chinese thought.

She lost all spontaneity and originality. To imitate became her

highest ambition, and she lost sight of all beyond this contracted

horizon. Intrinsically and potentially the Korean is a man of

high intellectual possibilities, but he is, superficially, what he is

by virtue of his training and education. Take him out of this

environment, and give him a chance to develop independently

and naturally, and you would have as good a brain as the Far

East has to offer.

Korea is a good illustration of the great influence which

environment exerts upon a people's mental and moral character-

istics. I am not sure that the conservatism of either the Korean

or the Chinese is a natural characteristic. The population of

China is so vast and so crowded, social usages have become so

stereotyped, the struggle for bare existence is so keen, that the

slightest disturbance in the running of the social machine is sure

to plunge thousands into immediate destitution and despair. At

this point lies the enormous difficulty of reforming that country.

It is like a huge machine, indescribably complicated, and so deli-

cately adjusted that the variation of a hair's-breadth in any part

will bring the whole thing to a standstill. Let me illustrate.

There are a great many foreigners in China who are trying to

evolve a phonetic system of writing for that country. It is

a most laudable undertaking; but the system which has received

most approbation is one in which our Roman letters are used

to indicate the various sounds of that language. But these letters

are made by the use of straight and curved lines, the latter being

almost exclusively used in ordinary writing. Now we know

that over two thousand years ago the Chinese discarded a system

based upon curved lines, because it was found impossible to make

them readily with the brush pen, universally used throughout

the Far East. The introduction of a system containing a large

proportion of curved lines implies, therefore, that the brush pen

will be laid aside in favour of a hard pen, either in the form of

our Western pen or in some similar form. Note the result. The

use of a metal pen and fluid ink will do away with the brush pen,

and will affect the industry whereby a million people make an

already precarious living. The manufacture of india ink will

likewise go to the wall. The paper now used in all forms of

writing will be useless, and a very few, if any, of the manufac-

turing plants now in operation can be utilised for the manu-

facture of the hard, calendered paper which is needed for use

with the steel pen. Moreover, the ink-stones, water-cups, writing-

tablets, and all the other paraphernalia in use at the present time

will have to be thrown away, and all the people engaged in the

manufacture of these things will be deprived of their means of

support. All this is likely to happen if the system proposed is

to become the general rule. Note how far-reaching even such

a seemingly small change as this will be. It might be possible

if there were any margin upon which all these people could sub-

sist during the process of change; but there is none. It is for

this reason that the present writer has urged that the Chinese

people be invited to adopt the Korean alphabet, which is as simple

in structure as any, and capable of the widest phonetic adapta-

tion. It is a " square " character, and could therefore be written

with the brush pen, as it is to-day by the Korean. The same

paper, ink, and other apparatus now in use in China could be

retained, and the only work to be done in introducing it is to

overcome the sentimental prejudice of the Chinese in favour of

the ideograph. It would affect the daily occupation of almost

no Chinese workmen at all. This illustration has gone too far;

but it will help to show how firmly these customs have sunk their

roots in the soil of these nations, and it shows that conservatism

has become a necessity of life, however much one might wish to

get rid of it. But let us get back to Korea.

The Korean is highly conservative. One of his proverbs is

that " If you try to shorten the road by going across lots, you

will fall in with highwaymen." This is a strong plea for stay-

ing in the old ruts. His face is always turned back toward

the past. He sees no statesmen, warriors, scholars or artists

to-day that are in any way comparable with those of the olden

times; nor does he even believe that the present is capable of

evolving men who are up to the standard of those of former

times.

But in spite of all this, he can be moved out of his conservatism

by an appeal to his self-interest. The introduction of friction

matches will illustrate this point. The Korean was confined to

the use of flint and steel until about thirty years ago ; but when

matches entered the country in the wake of foreign treaties, he

saw almost at once that they were cheaper and better in every

way than his old method, and he adopted them without the least

remonstrance. There were a few fossils who clung to the flint

and steel out of pure hatred of the new article, but they were

laughed at by the overwhelming majority. The same is true of

the introduction of petroleum, sewing-needles, thread, soap and

a thousand other articles of daily use. The same is true in

China. There is no conservatism that will stand out against

self-interest.

And here we touch a second characteristic of the Korean.

It cannot be truthfully said that the Korean is niggardly. It has

been the opinion of most who have had intimate dealings with

him that he is comparatively generous. He is generally lavish

with his money when he has any, and when he has none he is

quite willing to be lavish with some one else's money. Most

foreigners have had a wider acquaintance with the latter than

with the former. He is no miser. He considers that money is

made to circulate, and he does his best to keep it from stagna-

tion. He thinks that it is not worth getting unless it can be

gotten easily. I doubt whether there is any land where the

average citizen has seen greater ups and downs of pecuniary

fortune. Having a handsome competence, he invests it all in

some wild venture at the advice of a friend, and loses it all. He

grumbles a little, but laughs it off, and saunters along the street

with as much unconcern as before. It went easily — he will get

some more as easily. And, to tell the truth, he generally does.

It is simply because there are plenty more as careless as himself.

He is undeniably improvident; but there is in it all a dash of

generosity and a certain scorn of money which make us admire

him for it, after all. I have seen Koreans despoiled of their

wealth by hideous official indirection which, in the Anglo-Saxon,

would call for mob law instantly ; but they carried it off with a

shrug of the shoulders and an insouciance of manner which

would have done credit to the most hardened denizen of Wall

Street. I am speaking here of the average Korean, but there are

wide variations in both directions. There are those who hoard

and scrimp and whine for more, and there are those who are

not only generous but prodigal. Foreigners are unfavourably

impressed by the willingness with which the Korean when in

poor circumstances will live on his friends ; but this is to a large

extent offset by the willingness with which he lets others live

on him when he is in flourishing circumstances. Bare chance

plays such a prominent part in the acquisition of a fortune here,

that the favoured one is quite willing to pay handsomely for his

good luck. And yet the Korean people are not without thrift.

If a man has money, he will generally look about for a safe place

to invest it. It is because the very safest places are still so unsafe

that fortune has so much to do with the matter. He risks his

money with his eyes wide open. He stands to win largely or

lose all. An investment that does not bring in forty per cent a

year is hardly satisfactory, nor should it be satisfactory, since

the chances of loss are so great that the average of gain among

a score of men will probably be no more than in our own lands.

Why the chances of loss are so great will be discussed in its

proper place.

Another striking characteristic of the Korean is his hospi-

tality. This is a natural sequence of his general open-handedness.

The guest is treated with cordial courtesy, whatever differences

of opinion there may be or may have been between them. For

the time being he is a guest, and nothing more. If he happens

to be present at the time for the morning or afternoon meal, it is

de rigeur to ask him to have a table of food ; and many a man

is impoverished by the heavy demands which are made upon

his hospitality. Not that others have knowingly taken undue

advantage of his good nature, but because his position or his

business and social connections have made it necessary to keep

open house, as it were. A Korean gentleman of my acquaint-

ance, who can live well on twenty dollars a month in the country,

recently refused a salary of twice that sum in Seoul on the plea

that he had so many friends that he could not live on that amount.

Seoul is very ill-supplied with inns ; in fact, it has very little use

for them. Everyone that comes up from the country has a

friend with whom he will lodge. It must be confessed that there

are a considerable number of young men who come up to Seoul

and stay a few days with each of their acquaintances in succes-

sion ; and if they have a long enough calling list, they can man-

age to stay two or three years in the capital free of board and

lodgings. Such a man finally becomes a public nuisance, and

his friends reluctantly snub him. He always takes this hint

and retires to his country home. I say that they reluctantly snub

him, for the Korean is mortally afraid of being called stingy.

You may call him a liar or a libertine, and he will laugh it off;

but call him mean, and you flick him on the raw. Hospitality

toward relatives is specially obligatory, and the abuse of it forms

one of the most distressing things about Korea. The moment

a man obtains distinction and wealth he becomes, as it were, the

social head of his clan, and his relatives feel at liberty to visit

him in shoals and stay indefinitely. They form a sort of social

body-guard, — a background against which his distinction can

be well displayed. If he walks out, they are at his elbow to

help him across the ditches; if he has any financial transactions

to arrange, they take the onerous duty off his hands. Meanwhile

every hand is in his rice-bag, and every dollar spent pays toll to

their hungry purses. It amounts to a sort of feudal communism,

in which every successful man has to divide the profits with his

relatives.